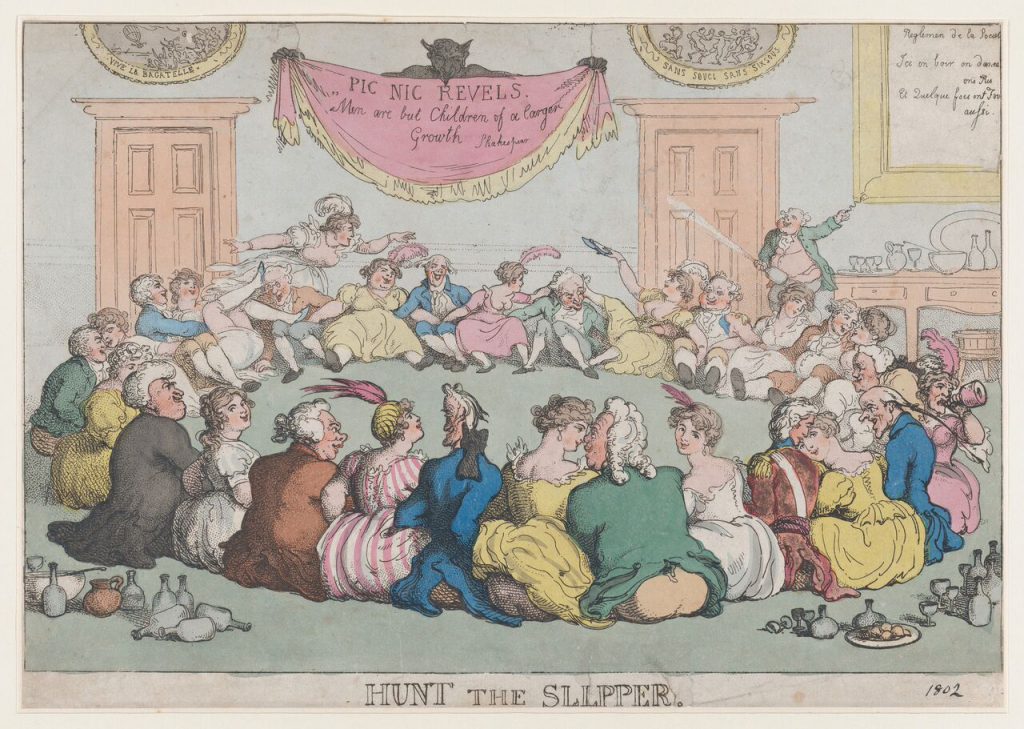

The latest in Albert Mobilio’s series of (very) short stories based on old-time games illustrates how the characteristics of play capture the essence of our lives.

A piece of earth on which two parallel lines are marked about sixty feet apart, with sidelines about fifty feet apart. Apartness. The sensation marks Jess’s sense of herself in the world. She’s popular, sure. And she knows that. People she hasn’t seen in years invite her to weddings and add handwritten notes to say how much it would mean if she came. At her old job folks loved Jess; even the mailroom guy who seethed at everyone when he rolled his cart past their cubes sometimes stopped at hers to cough a bit and apologize with words almost indistinguishable from the coughing.

Sandy takes her position in the middle of the field and issues the chaser’s required challenge, “Pom-pom-pullaway, come away or I’ll pull you away.” The singsong quality she hears in her voice is cause for sudden but unnecessary embarrassment; how else utter so alliterative a threat. Put those words in Scarface and Pacino would have to croon them just the same. No matter, she is acutely aware that Jess heard the trilling notes. The sun eases through scattered clouds mottling the meadow’s slopes and Jess stands slackly, hand on hip, in a blanket-size patch of shade. A casual indifference seems to dictate every angle and curve; she looks like she was poured into place. If Sandy could see Jess’s face she’s sure she would find no more than a hint of a smirk because for that girl a smirk is emoting like Sarah Bernhardt. Sandy doesn’t want this in her head about Jess but it is. Look at her, just poured there.

Once her call is complete, the runners make a beeline for the goal behind Sandy while she tries to tag someone three times. If she does that person joins her for the next call. Jess is close enough to pursue—in fact, she’s the closest player—but does Sandy really want to do that? But if she doesn’t her disinclination will be obvious. The decision, though, is made by Jess who comes on hard, buoyed above the high grass by long, loping strides, right at her friend. The clouds have freed the sun’s full force and the entire field vibrates with sudden warmth and thrumming feet. Sandy runs, too, aiming to meet Jess at an angle, but she can’t keep that line of attack because Jess matches her, side-step for side-step, to keep them on track for a head-on collision. She’s playing chicken, Sandy realizes. She wants to see me duck.

Despite the elegance of Zeno’s paradox—one always has half the distance to their goal to travel therefore they will never reach it—these two players will surely meet. Zeno will not intervene to reassure them that when they are, say, the width of a molecule apart, they still have to traverse half a molecule and a quarter molecule after that and so on. He will not alight twixt them to guarantee no bruises today. Sandy extends both arms; either way Jess moves she wants to be ready to reach her. Doing so slows Sandy’s stride but that doesn’t matter—she only has to tag the woman now bearing down on her, shedding her last traces of because for that girl a smirk is emoting like Sarah Bernhardt. Sandy doesn’t want this in her head about Jess but it is. Look at her, just poured there.

Once her call is complete, the runners make a beeline for the goal behind Sandy while she tries to tag someone three times. If she does that person joins her for the next call. Jess is close enough to pursue—in fact, she’s the closest player—but does Sandy really want to do that? But if she doesn’t her disinclination will be obvious. The decision, though, is made by Jess who comes on hard, buoyed above the high grass by long, loping strides, right at her friend. The clouds have freed the sun’s full force and the entire field vibrates with sudden warmth and thrumming feet. Sandy runs, too, aiming to meet Jess at an angle, but she can’t keep that line of attack because Jess matches her, side-step for side-step, to keep them on track for a head-on collision. She’s playing chicken, Sandy realizes. She wants to see me duck.

Despite the elegance of Zeno’s paradox—one always has half the distance to their goal to travel therefore they will never reach it—these two players will surely meet. Zeno will not intervene to reassure them that when they are, say, the width of a molecule apart, they still have to traverse half a molecule and a quarter molecule after that and so on. He will not alight twixt them to guarantee no bruises today. Sandy extends both arms; either way Jess moves she wants to be ready to reach her. Doing so slows Sandy’s stride but that doesn’t matter—she only has to tag the woman now bearing down on her, shedding her last traces of insouciance. The air is heavy, yet Sandy detects a quickening swirl beneath her flung-apart arms. Is that what pilots call lift? Jess is half of a half of a half away and Sandy believes that if she were to leap she could be airborne. ♦

Missed earlier stories? Find them here, here, and here.

(Image credit: Lewis Wickes Hine. Recess games in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)