Critic Martin Herbert has spent a lot of time with artists in their studios. Here he talks about how some of his hosts distinguish between working and their work.

Musicians play. Artists, meanwhile, typically make works. You might ask why—is the terminology a defense against philistine suspicions that artists are pulling a fast one, little real work involved? Does it, conversely, serve as a psychological reassurance for artists themselves that they’re making genuine effort, an equivalent of male writers—from Dickens to Hemingway to Nabokov—using a standing desk? The first irony here is that “work” is something of a misnomer, in the experience of this frequent lurker, for what transpires in artist’s studios.

Not that artists don’t put the hours in. The German artist Wolfgang Tillmans once told me that he puts in an eight-hour day in the belief that being there simply increases the chances of a good result (a principle known to writers as “ass on seat”). The British artist Mark Wallinger, recounting a period where he’d just finished a major series and didn’t know where to go next, told me he’d sit in the “thinking room” of his two adjoining studios—often all day—and wait until he had half an idea, then pin it to the wall; the next day he’d come in and try to catch the other half. Another British painter I know spent this summer bowling up to his studio around 5am and says he couldn’t have been happier. But the work here is primarily showing up, not what goes on during the studio time, and probably the more the artist says to themselves “I am working,” the more likely a neurological shutdown is to occur: like trying hard to remember a name, the part of the mind that needs to be flexible and free is tied up with something else.

For artists, “play” is now a problematic word.

One close analogue to what goes on in the creative process—speaking as a writer and sometime improvising musician—is Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s concept of “flow.” The Hungarian psychologist breaks this down into nine component states, but it adds up to a condition—one comparison he makes is, indeed, with playing jazz—where the whole body and mind are engaged and unified (the result might also be called “where did the last four hours go”). Also—particularly in sports—called being “in the zone,” flow was theorized by Csíkszentmihályi in the mid-’70s, but inevitably it’s a much older idea. In The Wisdom of Insecurity (1951), Buddhist popularizer Alan Watts writes that “This is the real secret of life—to be completely engaged with what you are doing in the here and now. And instead of calling it work, realize it is play.” But artists don’t quite want to play either, not least because “play” is now a problematic word.

In the mid-century counterculture that Watts’ work helped midwife, play was an anarchic categorical inverse of workaday living, of “straight” culture: see, for example, Richard Neville’s picaresque 1970 manual Play Power. Fast forward, and along with the counterculture itself, play has been recouped. We are all supposed to be playing now: gamifying our inbox management, erasing the line between labor and fun, every wage slave a self-starting creative. This leaves play as a suspect category. And, to return to ironies, it’s partly if unwittingly the fault of the artist—as the avatar of neoliberal individualism and mobility, the person who is never really working despite making “works,” because they do what they love—that that’s happened.

The word “work” forced me to reconsider assumptions about leisure.

A few years ago the American artist Carol Bove, herself a questioner of the residual givens of the ’60s, told me she’d banned the word “work” from her vocabulary. More recently, in an essay, she expanded on the experiment:

“I discovered that the absence of the word “work” forced me to reconsider assumptions about leisure, because the idea of work implied its opposite. I let go of the notion that I deserved a certain amount of downtime from being productive or from being active. The labor/leisure dichotomy became uncoupled and then dissolved. I couldn’t use labor to allay guilt or self-punish or feel superior. Work didn’t exist, so all the psychological payoff of work for work’s sake had nowhere to go. I started to adjust my thinking about productivity so that it was no longer valued in and of itself. It strikes me as vulgar always to have to apply a cost/benefit analysis to days lived; it’s like understanding an exchange of gifts only as barter. The work exercise made me feel as if I was awakening from one of the spells of capitalism.”

What, Bove asked, is an artist’s activity if it’s not work? You don’t want it to be work because work is now ideological, used in the services of biopower; and so now, in its way, is play. Creativity, for the artist, is the result—powered often by intuitive leaps—but it’s not the state. How, then, to categorize what goes on behind the studio door? I’ll address this to any corporate-management types who might happen to be reading: there is a word for what happens there.

It isn’t work. It isn’t play. It isn’t even flow. There is a word, and a definition too. But I’m not telling you what it is. ♦

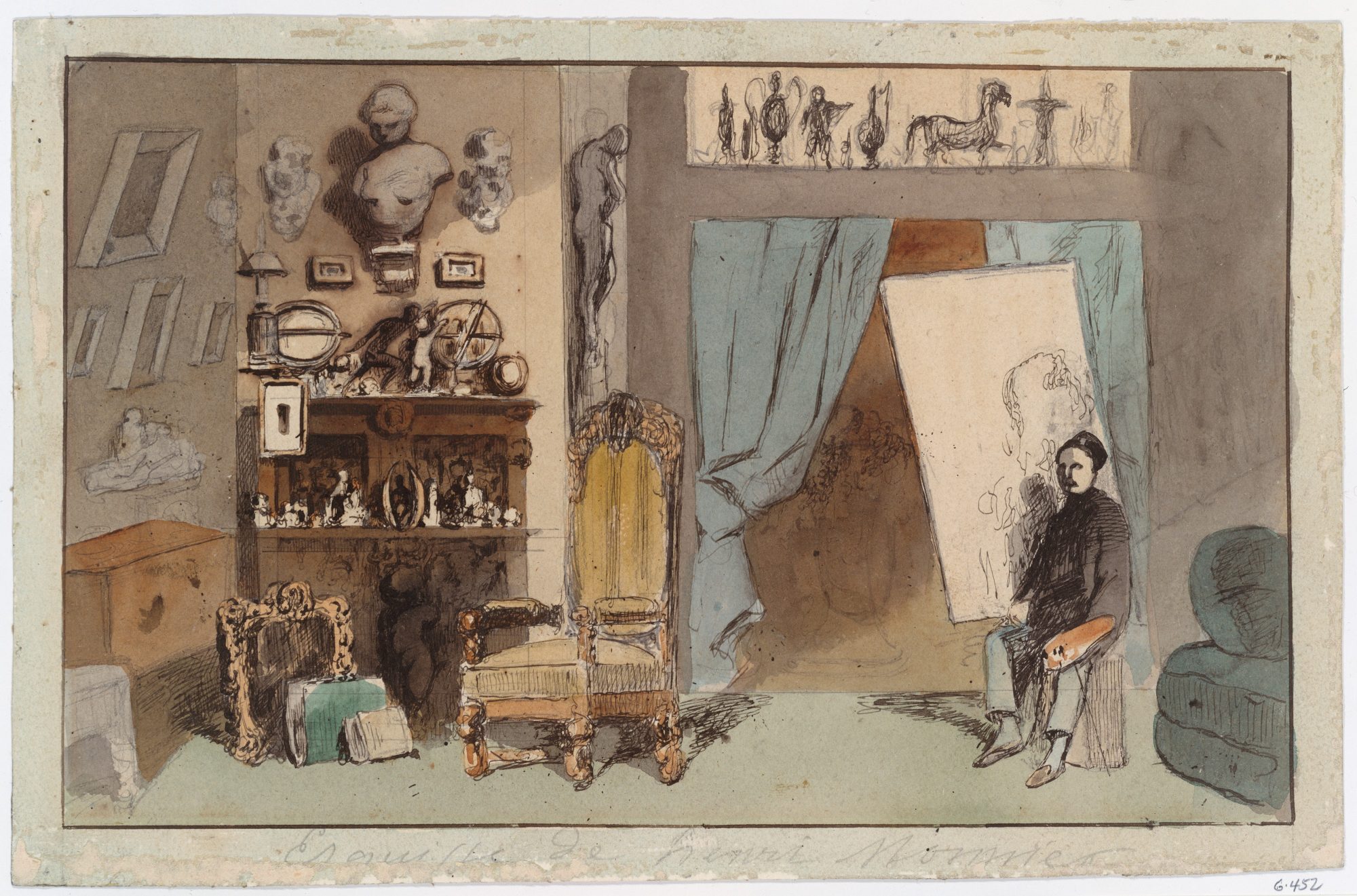

(Image credit: Henry Henri Bonaventure Monnier, The Painter’s Studio, about 1855. Robert Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)