How do childhood experiences of play shape us? The magical and the ordinary converge in artist and writer Tamara Shopsin’s story of a museum visit with her friends and their children.

I spot a backpack that suggests a suspension bridge and know it belongs to Leo. His younger brother Sid is playing next to him. The boys and backpack belong to our friends Yuri and Mike.

Jason, my husband, calls out to Mike.

Sid offers me a salad dressing–flavored breadstick. I am touched by this. There are only six in a pack, and he has just dropped one down a hole to watch it fall.

There are no trash cans on the street. I keep a plastic bag in my purse that I empty each night in our hotel room. I offer to take Sid’s garbage, but Yuri also has a trash bag in her purse that she empties each night.

A few more blocks and we come to a park entrance.

“Nihon Minka-en” is translated on the green and yellow information map as “Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum.” It is a campus of twenty-five historic farmhouses.

•

My change is handed back on a blue tray with a complimentary postcard. We follow the route arrows into an exhibit hall.

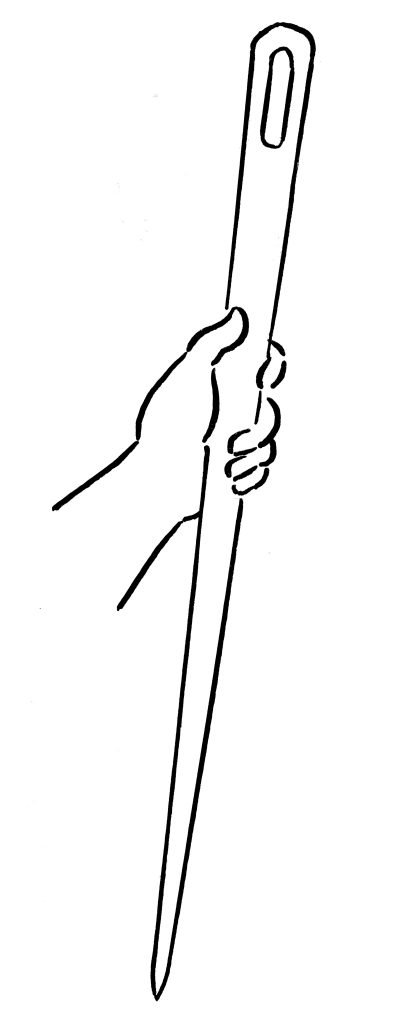

On the wall is a photo of two men sewing a thatched roof to a house. One man stands outside feeding a giant needle through the straw. The other sits inside acting as a human bobbin, locking the stitch. Under the photo in a glass case is the giant needle. It’s made of bamboo and is threaded with rope thick as a cucumber.

There is a light drizzle. Clouds surround us, blocking everything except a stone path, Japanese farmhouses, and some trees. A Samurai film could be shot here with no propping.

This house belonged to wealthy farmers. We sit on a ledge in its entryway and take off our shoes. The floors are soft.

Jason tells me to check out two screens decorated with a zig-zag pattern. I don’t get why, but then I tilt my head and an intense moiré pattern is created.

Around the side of the house, ladies are weaving. Leo has his back to them. He is chasing a cricket. Sid sees and joins in. Leo says something in Japanese, and Sid makes his hands into a cup.

On the stone path, I smell fire and wet trees.

•

Two more houses, and the path starts to curve up a hill. We walk beside a roof made of shingles secured with rocks like a paperweight. The roof is slanted. I am not sure why the rocks don’t fall off. Jason isn’t impressed, but I am. It takes balls to be that simple.

•

The path has gotten bushier with a cluster of cold weather farmhouses that have steep thatched roofs designed to help snow slip off.

The roofs need to be redone every twenty-five years. A whole village must chip in to help. Because if the roof isn’t done in a day, the exposed straw can spoil and rot. The construction time constraint could be taken as a design flaw, but is the opposite. It makes the village stronger.

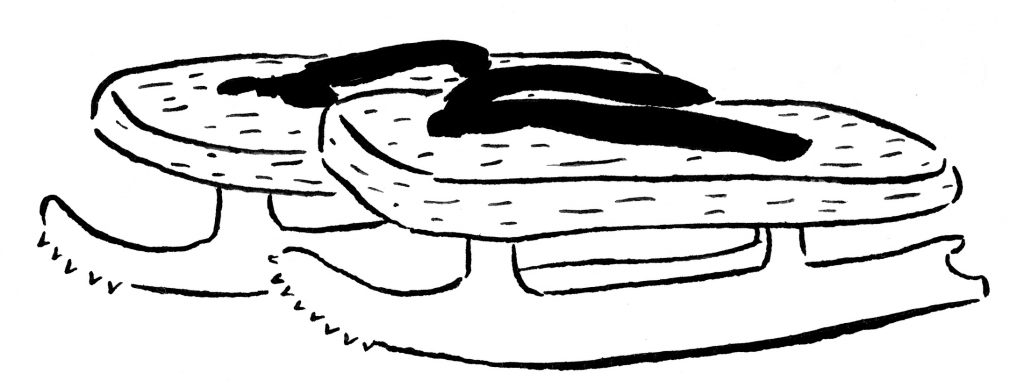

Edo era ice skates

A sign on the shoe rack warns to be careful. Someone recently put another person’s shoes on by mistake.

This folk house is dim with dark wood. Sid sits and draws the paper lanterns that glow yellow. The only other light source comes from a spinning jewelry case of fake food, illuminated by a fluorescent bulb.

I buy us blue and yellow tokens that represent lunch and dessert.

At a low table Jason awkwardly bends his knees sideways. Mike tells us about his friend who believes slurping is good for eating not just hot food, but all food. The friend has a theory that the addition of air makes everything taste better.

We all slurp our soba, except Sid who only stops drawing to ask us what he should draw.

•

Pupils are lines instead of dots. Fire is shaped like a sword rather than an ivy leaf. Tiny things, but the way Sid draws already looks Japanese.

Sid’s dragon

My first babysitter was named Mary. I loved her deeply, but can remember only four things about her:

1. Sometimes she would accidentally tuck her hair into her pants.

2-4 Are things she taught me to draw…

•

Another house. The docent cracks jokes about locking us in. He slides a wall shut. A hand making the sign of the beast juts through a hole in the door that is a wall.

Yuri translates, explaining it is a seventeenth-century cat door and that is a hand signal for cat in Japan, not hail Satan.

•

We see a shrine and then a ferryman’s hut that are about the same size.

At a crossroads with a vending machine and a river, the boys take the river and we drink warm cans of milk tea.

The boys catch a grasshopper. It is in Leo’s hands. They want to keep it. Mike searches his bag and pulls out a water bottle. Sid chugs the water and hands it to Leo.

“I can’t put the cap on—there are no air holes. Can you poke some?” Leo asks.

“I didn’t bring anything to do that,” Mike answers.

Leo carefully folds a handful of grass and shoves it into the bottle, giving the bug its own thatched roof. ♦