Writer and game designer Kat Brewster looks into game playing as a constructive means in this first post of a two-part series.

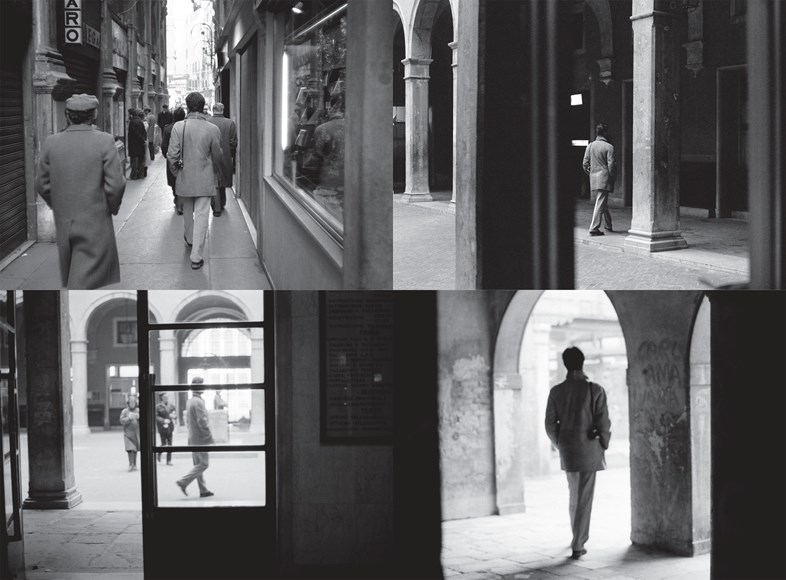

In 1979, Sophie Calle returned to her native Paris after an extended period of traveling, and felt restless. “I felt completely lost in my own town,” she said. “I no longer knew how to occupy myself each day, so I decided that I would follow people in the street.”1 Calle reasoned that if she did not know what to do in Paris, other Parisians could show her. So, like a game of cat and mouse, she followed them. Just to see where they went. In this way, she says, “I let them decide what my day would be, since alone I could not decide.” When one of Calle’s subjects showed up at a party she attended that evening, she thought it was a sign. When he mentioned that he was traveling to Venice, she upped the ante. Calle’s following spiraled into an international chase as she, in a blond wig and trench coat, followed the man from Paris. She photographed Henri B., as she called him, for two weeks around the Italian city. When he finally confronted her, the game ended. The photographs Calle took and her accompanying diary became the artist’s first published work: Suite Venitienne.

“I did not consider myself to be an artist,” Calle later said of this phase in her life. “I was just trying to play, to avoid boredom.”

“Boredom,” as the German literary critic Walter Benjamin wrote in the notes for his unfinished Arcades project, “is the threshold to great deeds.” Play, like Calle’s, is often an activity born of restlessness, engaged with to alleviate a sense of stagnation. The Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johann Huizinga defined it in 1938 as “a free activity, standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as ‘not serious,’ but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it.”2 Huizinga’s eighty-year-old definition is a popular one, and has served well for a foundational understanding of the activity. Play is a process which exists separately from a player’s ordinary life, or the common denominator of their lived experience. It is also considered to be done purely for the sake of it without the hope of profit. It is for these reasons that the activity is frequently derided in Western capitalist societies, particularly in adults. “I was just playing,” one might say to extricate themselves from a social faux-pas. “Stop goofing around, be serious.” “This isn’t a game.” “Don’t play with me.” These phrases serve to reinforce a culture which devalues play.

Boredom is the threshold to great deeds.

When play is both not real and not for profit, its worth in a society reliant on a hierarchy of tangible production is precarious. The eight hour workday, established in large part in the 1880s, was intended to delineate productive labor from self-directed pursuits and rest. For the artist, however, that barrier between productive labor and creative labor—that which is typically expected to fill one’s leisure time—is a more permeable one. Indeed, it could be said that all artistic practice is a departure from typical labor, and in turn, deemed “not-serious.” Play and art both are often considered fruitless pastimes. In large part, the high-school graduate who tells their parents: “I want to be an artist,” strikes more fear than saying, “I want to be an economist.” That is, depending on the parents.

Children are granted an amnesty in playtime. Child psychologist D. W. Winnicott championed the child who plays as one who is rationalizing the boundaries of acceptable behavior, engaging in what he deemed “reality testing.”3 The same could be said of the radical artist, who shifts and renegotiates cultural boundaries and understanding. Whether simply for themselves, or through large-scale exhibitions, modern and contemporary art has been shaped by playful practice and deviating from an established ordinary. They elevate the activities relegated to simple leisure, often experimental and stimulating, to the status of “high art.”

Returning to Calle’s Suite Venitienne, with its focus on play and distraction, it is clear that hers was an intentional deviation from the monotony of her fraught Parisian life. She projected herself into a thrilling fiction, and where she previously felt directionless and lost, she now had purpose. “There were photos and notes,” Calle said. “Being in control, losing control, making up for emotional gaps, becoming attached to someone, if only for half an hour.”4 Play is the only activity where one may perform what one isn’t, to see what it is like. It is a safe space for self-exploration. Calle plays at being out of control through a strict set of rules, and creates a game.

Calle, of course, is not the only artist to have gotten their start in play, or in avoiding the mundane. Within the confines of the formal art world, perhaps the most celebrated deviation from an established ordinary is the Salon des Refusés. Following the rejection of an unprecedented 3,000-plus paintings to the 1863 Paris Salon—a juried show sponsored by the French government and the Academy of the Fine Arts—Napoleon III had their works exhibited in a parallel show. The exhibition was called the Salon des Refusés, or, The Salon of the Refused. Though Napoleon III perhaps had intended to solely balm the sting of refusal, he also succeeded in legitimizing a state-approved alternative to the academy. Suddenly, there was more than one way to achieve recognition, funding, and patronage. Those artists shown in the parallel show rejoiced in their relegation of refusal, and endured the initial ridicule which the exhibition incited, and eventually they would become one of the most celebrated groups in modern art: the Impressionists.

Check out part two of this essay—with the Impressionists and Dadaists at play—here.

1 Curiger, Sophie Calle in Conversation, 50.

2 Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 13.

3 Winnicott, Playing and Reality, 6.

4 Macel, Biographical Interview with Sophie Calle, 77.

(Image credits: Image © Sophie Calle, published by Siglio Press. “Palais de L’industrie, Paris Exposition, 1889,” Henry Clay Cochrane Collection at the Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections, Quantico, VA, via Wikimedia Commons.)