Art writer Dan Fox unpacks the performative nature of work and the misconceptions of play as work.

Traveling salesman Alfredo Traps—hapless protagonist of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s 1960 novel Die Panne (The Breakdown)—is stuck in a small village waiting for his car to be repaired. A retired judge, who occasionally takes in guests, agrees to put the salesman up for the night in his large house. He asks Traps to have dinner with him. They’re joined by three old friends of the judge—two retired lawyers and a local publican, who goes by the nickname of “the executioner.” The elderly lawmen explain to Traps that they like to play a game whenever they meet, assuming their old professions to re-stage historical trials; Socrates, Jesus, Joan of Arc, Dreyfus, the Reichstag Fire. Rarely, however, do they get to play with “living material,” and so Traps is invited to participate as the defendant. Finding the situation amusing, the salesman agrees.

Over a lavish dinner, Traps is genially cross-examined by the two lawyers, one acting for the prosecution, the other as his defense counsel. Although the salesman is intellectually out of his depth, the lawyers are at pains to make him feel welcome and they ply him with wine. The prosecution lawyer plays his role with relish, and is tenacious in his interrogation. He eventually coaxes Traps into confessing that he slept with the wife of his boss. The salesman tells them how discovery of the affair caused his boss to suffer a fatal heart attack, leaving a vacancy in the company that Traps then filled. The court finds Traps guilty of murder and he is symbolically sentenced to death. The lawmen are thrilled with the trial verdict, raising toasts to Traps for being such a good player and letting them reach such a gruesome sentence. Over digestifs, the judge and his friends wax philosophical, explaining to the salesman that the law is nothing without crime, and that as a convicted murderer, Traps is an indispensable, even cherished part of a system that is as immutable as nature. Blind drunk, emotional, and now convinced that he is a gearwheel in a perfect, cosmic cycle of justice that only he can complete, Traps hangs himself. “Alfredo, my good Alfredo!” cries the judge when he discovers the salesman’s body. “For God’s sake, what were you thinking of? You’ve ruined the most wonderful evening we’ve ever had!”

Traps has played the game too well. He wants badly to be part of the team, and so at his trial, desperate to be respected alongside the successful professionals at the table, from his place in the dock he turns in the best performance he can, and that’s what kills him.

I imagine Traps to be the type who might describe himself on a resume or online dating profile as one who “works hard and plays hard,” as if “playing hard” is something to be respected for, part of the Protestant work ethic. Leisure as a form of labour that can be measured by how much sweat you spill in the gym before work starts, by the amount of money you spend on a business lunch, and by the number of drinks you down with your co-workers at the bar after the office closes. In the English speaking world, the word “play”—from the Old English “plegian,” meaning to exercise—slides its meaning easily between work and leisure contexts. Playing is what children do, an important part of their development into adults who will go on to spend their lifetime working. Plays are also what professional actors, directors, playwrights, and technicians produce for theaters. And “player” is an old theatrical word for “actor,” both of which are terms the military use to describe participants in war simulation games. Games conducted with lethal toys but which are, like stage plays, intended as exercises in human behavior carried out under controlled conditions. Players can be found in classical orchestras and pop bands, and earning millions of dollars as professionals on the football field and basketball court. Work and play are conventionally understood to be opposing, distinct activities; one is productive and earns money, the other is used for spending earnings and relaxing in preparation for more work. We call this the “work-life balance,” never the “play-life balance” yet work and play are wound tightly around each other.

What the artist calls work is what most of us would think of as play.

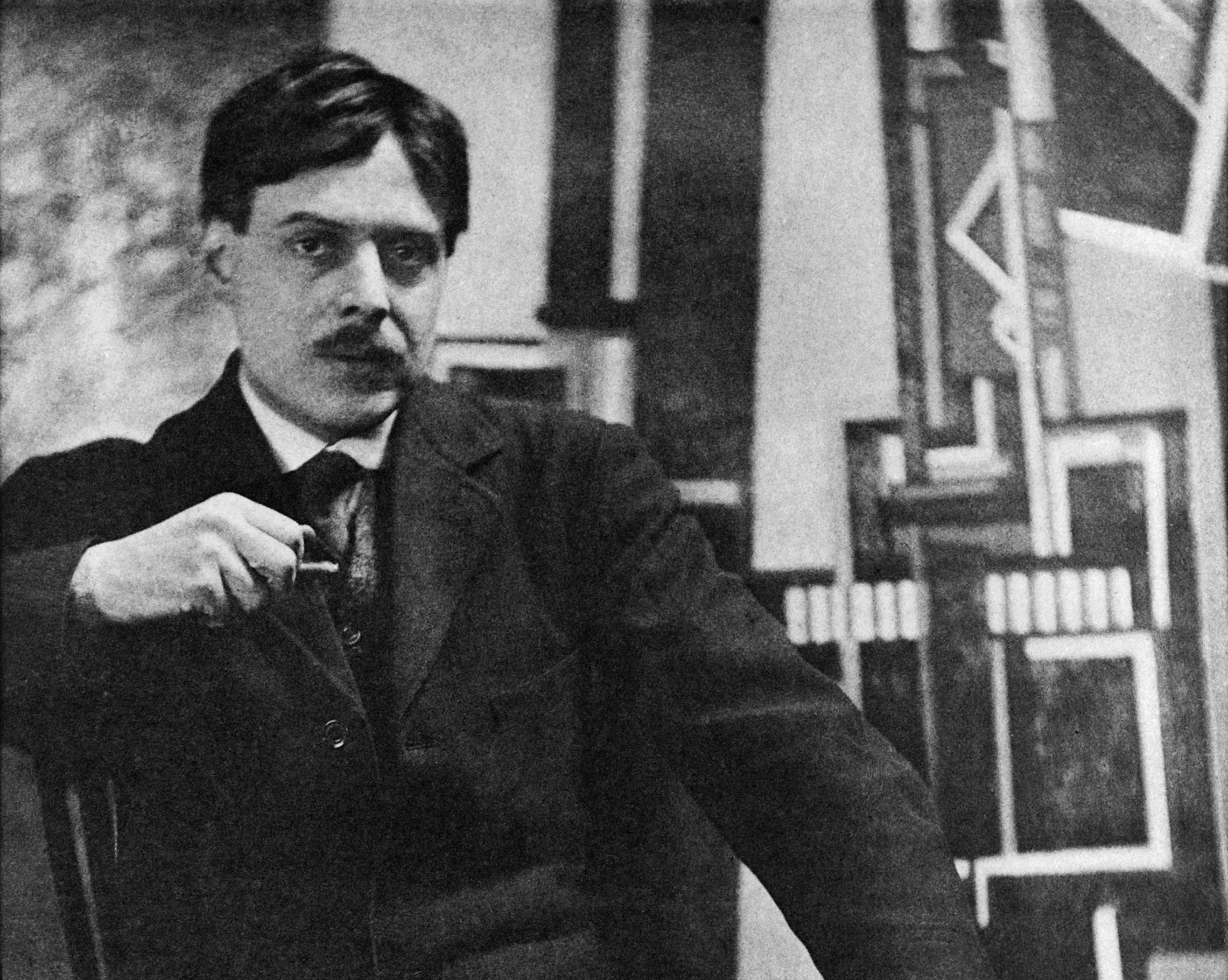

The double helices of work and play shape the profession of the contemporary artist. Like dentists, architects, and doctors, artists today have “practices.” They are freelancers who always need to be “on,” developing new bodies of art through “research” and using social time to network with gallery dealers, collectors, critics, and curators to ensure what they do is shown in the right institutional contexts and sold into the best collections. (And perhaps it was ever thus: in the 1920s, a friend of the British artist Wyndham Lewis pleaded with him to wear a boiled shirt at least four times a week, “for the sake of your career!”) At the same time—at least in the popular imagination—the artist represents a form of freedom from work, a licensed bohemian engaged in a socially acceptable form of madness. We are still attached to a Romantic idea of the artist-as-seer, whose role is to speak some kind of cosmic truth through their chosen medium that will result in an individual or society experiencing a change of consciousness. (See: “challenge audience assumptions,” “undermine the viewer’s expectations,” and other curatorial spells to ward off irrelevancy.) What the artist calls work is what most of us would think of as play, yet society grants the artist permission to call their play a form of work. Not that the artist needs this permission: for many artists, they could not imagine life without making images or objects.

These days, “creativity” is understood as a useful asset in the work place. (The word “creative” is now as much a job title as it is an adjective.) It is a semi-mystical quality that management theorists believe, if conducted through the correct use of flip-chart brainstorms sessions, Post-It notes, and team trust games, can be harnessed to help fix HR issues or provide the key to solving a project brief. Jobs are “performed,” we are assessed on how well we “act” on behalf of our employers. Uniforms are costumes, company stationary and office decor are set dressing that sets the tone of the work environment. Your local coffee shop is theater, your office is theater, the UN Security Council Chamber is theater. And in these places things are done by humans who are naked underneath their costumes, who eat, shit, fuck, laugh, cry, worry, like everyone else. We are all playing at being grown-ups.

The artist has something to give to the game, and is invited to play.

Perhaps our friend Traps is not that different to the artist, and the judge, lawyers and executioner analogous to the art system that enables them. The artist has something to give to the game, and is invited to play. Depending on how skillfully they navigate the interrogation, what readings can be made of their work, how sympathetically they play to the judge, a verdict will be passed and sentence handed down, to be recorded in the art historical ledger. The cycle of interpretation and judgement cannot be completed without the artist. In the Epistles to the Romans, Chapter 7:7, the apostle Paul writes: “I have not known sin but by the law.”

Have I not known art but by the game that names it?

(Image credit: British author and artist Wyndham Lewis photographed by Alvin Langdon Coburn in London, in 1916. Courtesy of Everett Collection.)