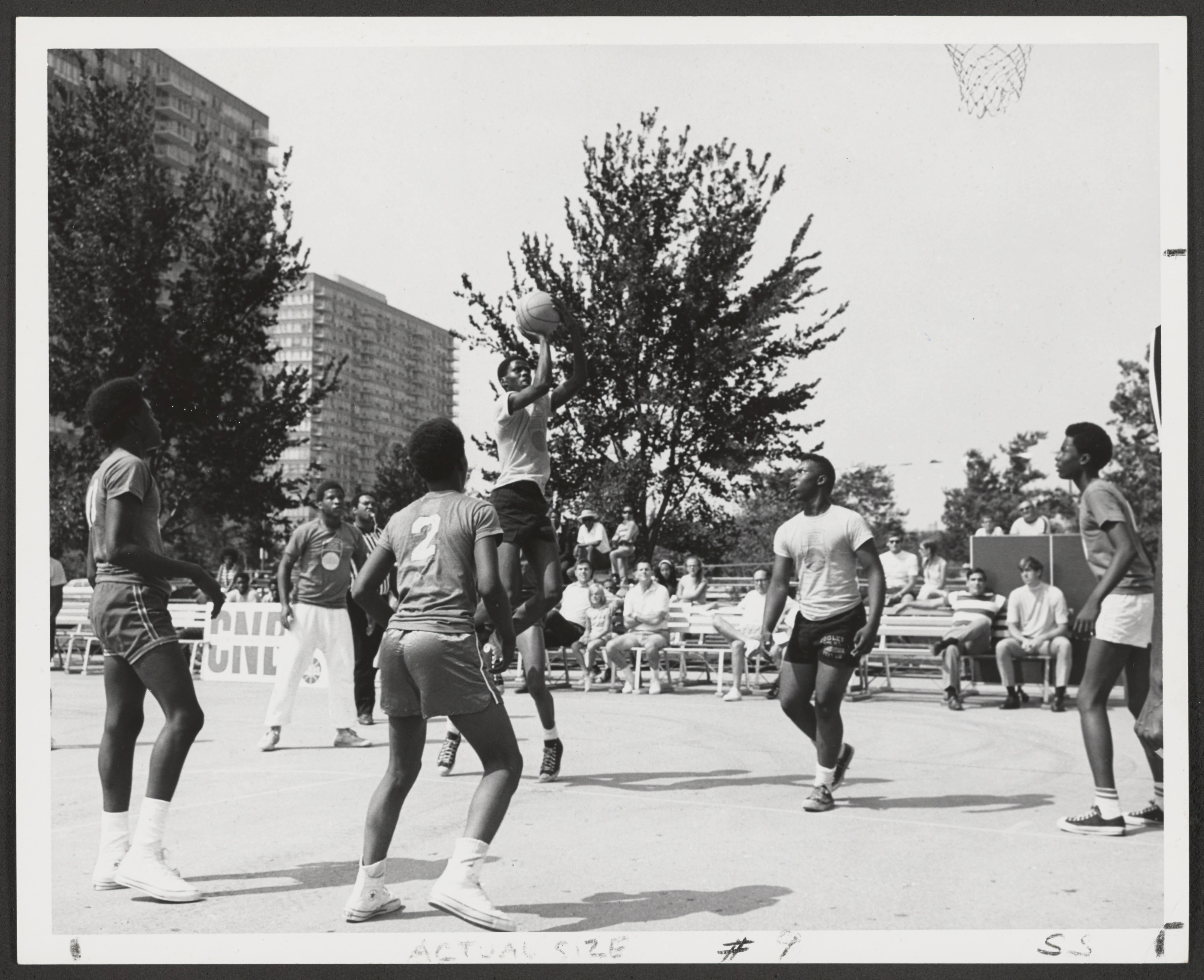

Carlo Rotella examines the threads of play in his upbringing in an essay in three sections. Here, in the second installment, we resume his story on the basketball courts of Chicago, where Rotella learned to navigate the complex social world of pickup basketball. Check out part 1 here.

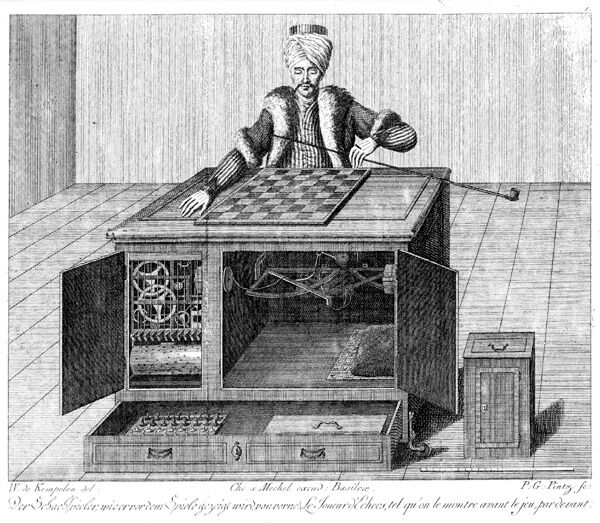

At the opposite end of the spectrum from the elaborate tactical board games over which I hunched for hours and days at a time as a child, learning the ins and outs of military strategy while perfecting the art of being alone, was pickup basketball: a laboratory for developing social self-knowledge and expertise. First, you had to get in the game. Say you showed up as part of a crew of four at a playground where a full-court five-on-five was in progress and there were seven guys already waiting. That meant there was a team of five ready to go next, with two left over. You’d have to figure out who those two were and size them up, then decide whether to a) sit out two more games until you and your whole crew could pick up one guy at courtside and constitute a team of five; or b) put forward three of your crew as teammates for the two current leftovers and thus get onto the court after sitting out only one game, though that would leave one of your number to fend for himself; or c) if those waiting seemed exceptionally weak or fractious or otherwise unequipped to defend their claim, brazenly declare that your crew had next and enlist the big dude in the cut-off Brothers Johnson T-shirt as your fifth. The negotiations could get tricky, with everyone assessing everyone else’s skill, size, confidence, willingness to back his own claim, and support from allies. If somebody tried to pull a fast one by claiming at the last moment, just as you and your crew were about to take the court to play your duly called next game, that he had actually called next way before but then had been obliged to go to take care of some business but had now come back, you had to decide whether to get all lawyerly in response or to simply brush aside this pretender, dismissing his claim out of hand as sorry-ass would-be gangster bullshit not even worth a reasoned rebuttal. However you played it, the main thing was to act as if you were the kind of guy who got in the game as a matter of course, and not the kind who could be pushed out of line with a strong-arm move.

I was obliged to cultivate the specific skill of playing with and especially against one’s betters, a skill not identical to being good at basketball.

Once in the game, I had to survive it. Because I hung out with serious players who tended to get me in with stiffer competition than my modest abilities rated, I was obliged to cultivate the specific skill of playing with and especially against one’s betters, a skill not identical to being good at basketball. My main challenge was to fend off humiliation when matched man-to-man against a member of the other team who, if we both did our best, could outscore me so badly that it would obviously be my fault if my team lost. That meant playing serious defense, which was not generally regarded as a principal virtue in pickup ball. I began by taking calipers to my man’s footwork, figuring out how much room he required to operate smoothly, then moved inside that limit, finding the sweet spot of his discomfort. I wanted to be just close enough that I was perpetually, irksomely there; rather than trying to prevent my man from doing what he wanted to do―get the ball, dribble, shoot―I just tried to make it unpleasant and difficult for him to do these things. By staying close and varying the rhythm of my intrusions to keep the irritation fresh, I could make him feel that there were extra feet where he wanted to step, extra bulk clogging up his movements. I used my hands on him as little as possible. I’d just follow, follow, follow, lining up my navel with his at the chosen distance and then trying to keep them lined up no matter what he did, so that he would begin to feel as if he was dragging around my body and will, my whole story, in addition to his own. I aspired to be like Jack Vance’s Chun the Unavoidable, who, even after the fleet and cruelly handsome Liane the Wayfarer slips into a sorcerous portable hole to escape him, shows up at Liane’s elbow in his coat of eyeballs and says, “I am Chun the Unavoidable.”

I appeared to be model citizen of the little commonwealth of the pickup team.

I appeared to be model citizen of the little commonwealth of the pickup team because I performed needful tasks that most other players, fixated on the universally acknowledged priority of racking up points, didn’t feel like doing. In addition to playing defense on my man with irksome persistence, I passed the ball to teammates with care and sensitivity, boxed out, rebounded, fetched loose balls, tipped away opponents’ passes, and ran the court on every possession. But this appearance of good citizenship was an illusion: other than wanting to win so that I could stay on the court, I was, at best, agnostic about the greater good of my teammates; at worst, I was willing to sacrifice them in the cause of preserving my own dignity. My basketball self, a bad person masquerading as a good neighbor, only incidentally made his teammates’ lives better by making opponents’ worse. Intent on holding my own by destroying my man’s virtuosity and dragging him down to my level, I regarded offense―the soul of the pickup game―as wildly overrated. Offense was mere slavishness posing as inspiration, a company man’s sorry campaign to make Employee of the Month. But defense―not the rah-rah kind but the I-live-you-die kind―was the essential business of denying your enemies their heart’s desire, which was to put your hamlet and crops to the torch and carry off your loved ones into the night.

Return to the first installment of “Ball Games and War Games.” Read part three here.

(Image credit: A pickup basketball game in Chicago’s Lake Meadow Park, 1970 (Lake Meadow Park (0263) Activities – Sports, 1970.). Courtesy of the Chicago Public Library.)