Carlo Rotella takes us on a playful meander through his formative years on Chicago’s South Side, remembering a youth spent shuttling between the solitary world of military board games and the complex social dynamics of the pickup basketball court. This is the first installment of a three–part series.

Growing up on the South Side of Chicago in the 1970s, I played the usual games. Indoors, I did most of my world-thinking with wooden blocks and toy soldiers, though we also had a tabletop hockey game that pitted the Blackhawks against the Bruins. One of the Bruins had somehow ended up with two backs and no front when we applied the decals that turned two-dimensional plastic blanks, centaur mergers of human and hockey stick, into men. The two-backed, no-faced Bruin lurched and flailed in a blind rage as he and his yellow-and-black teammates and red-and-black opponents, each mounted on a rod and constrained in his own slot like a chained dog, chased the skidding, rolling puck up and down the pasteboard ice.

Street football, especially when played two-on-two, reduced the sport to a permutative series of binary deceptions.

Outdoors, I played chase, guns, Moose and Wolves, and other such hunting- and fighting-themed games, and there was an across-the-street guts Frisbee mutation that resembled doubles tennis, but mostly I played ball. Street football, especially when played two-on-two, reduced the sport to a permutative series of binary deceptions―fake going long and stop short or vice versa, fake a pass and run or vice versa―periodically interrupted by someone calling out “Car!” and then a pause while we all struck postures of enforced idleness as we let traffic pass. I played baseball-derived rubber-ball games adapted to street (piggy move-up), sidewalk (running bases), stoop (pinner, also known as ledge), wall (strikeout), and schoolyard (all of them). I did some of my earliest batting in a side yard squeezed between two bungalows, so at first I drove everything back up the middle, a fine professional hitter in the making, until I graduated to regular fields and devolved into just another lout dead-pulling everything to left. When we had enough kids and a suitable stretch of grass, we played sixteen-inch softball―a barehanded variant, fetishized in Chicago, suited to showcasing the potency and grace of fat men. Fielding a lumpy, much-hit old sixteen-inch ball was like handling an overripe cantaloupe, but catching a new one fresh out of the box, rock-hard and blindingly white, felt like flagging down a cannonball. I avoided playing with these finger-crushing juggernauts because I needed my hands in working order to play pickup basketball, which I did in driveways, backyards, schoolyards, parks, gyms, wherever a rim and opposition could be found. One driveway court had several inches of ankle-threatening length of pipe coming out of the pavement under the basket, and another had no corners and a high hedge that played permanent impartial zone defense against anyone attempting to shoot from the left wing, but we played the changes, as musicians say: you got an extra point if you made a basket from behind the hedge.

As I entered my teens, two kinds of play rose to dominance. Among ball games, pickup basketball defeated all comers to become the sport of choice. It was the most formally complex and satisfying of our ball games, a chess among checkers, and so navigating inside its workings offered the most intense pleasure: the forking intricacy of the pick and roll, the cavalry-charge momentum of the fast break. Of all our ball games, it was the most obviously connected to advanced versions one might see on TV or in an arena. Street football or piggy didn’t look much like real football or baseball, but a steady two-way flow of style and players joined the pickup basketball circuit to uniformed, referee-supervised, clock-bound league play on the high school and college levels. And the man-to-man ethos of the playground game most closely resembled the most advanced version of all, the pro game played in the NBA, where zone defense was outlawed. Also, because basketball was known as a Black Thing and therefore endowed with special cachet on the South Side, competence in it was expected of a game-playing boy, especially one who wanted to explore the city and engage with people. Pickup ball gave me a plausible reason to show up with a crew somewhere I otherwise didn’t belong, negotiate with strangers on the sideline to claim a spot on the court, and run that court with a confidence that transmuted it from a strange place to one located on my expanding map of the world.

War games were almost entirely a solitary pursuit, somewhere between reading a book and writing one.

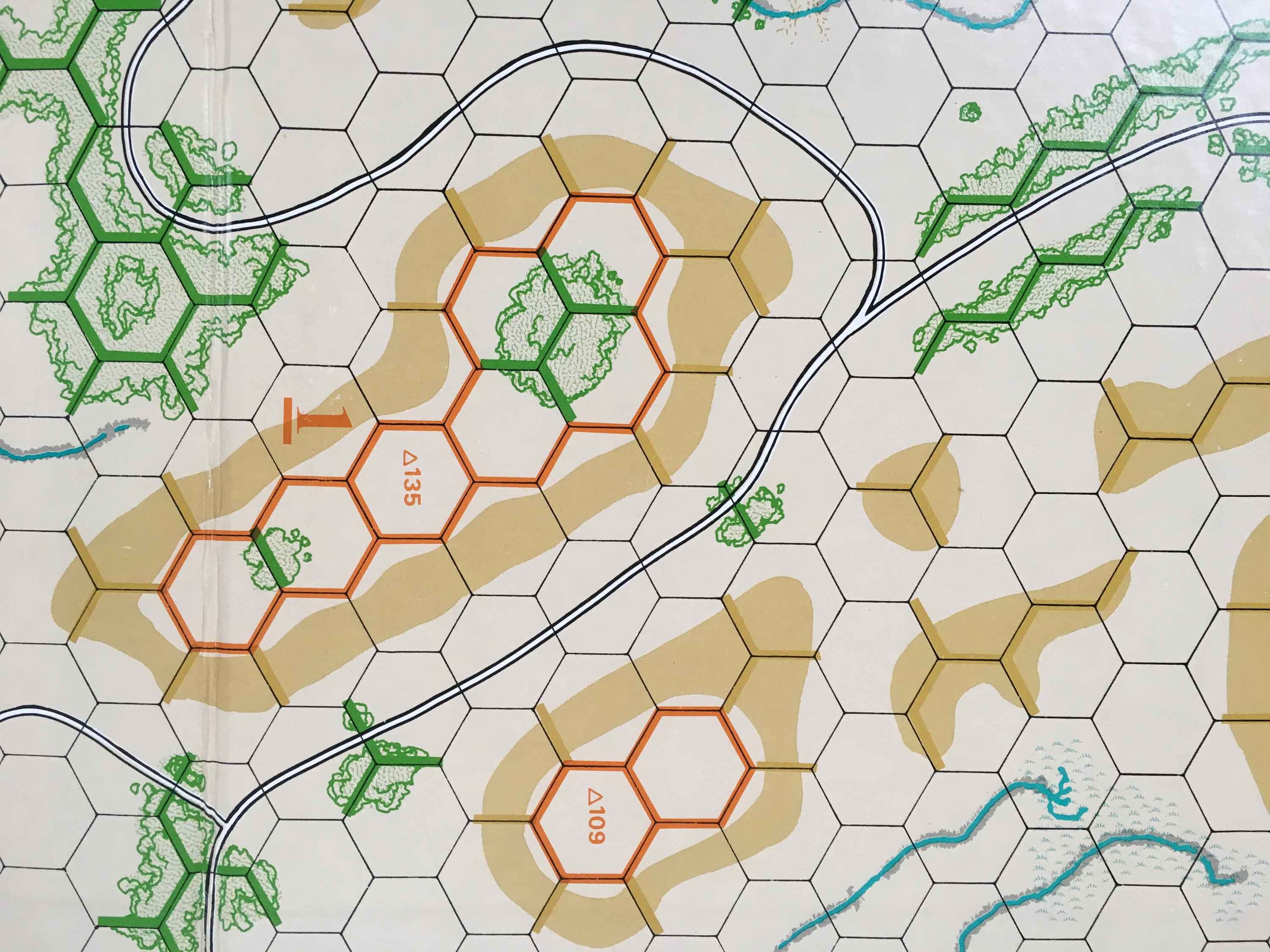

Among sedentary indoor games, military simulations gradually conquered everything else. I had progressed from murmuring “dooge” while knocking over green army men to laying out elaborate period dioramas of Airfix HO-scale miniatures―Napoleonic, Civil War, Second World War―to working out rudimentary rules to put those tableaux vivants in motion as war games. At some point it grew unseemly to play with toy soldiers, just as it had grown unseemly to run around on the block making gun noises, though the formal elegance of maneuver in miniaturized landscapes still drew me. When I discovered the martial board games made by Avalon Hill and Simulations Publications, Inc., the toy soldiers went into permanent storage, Wellington’s Highlanders and Union artillery and the French Foreign Legion all entombed in the same box in a promiscuous jumble. The war games had inch-thick rulebooks that reeked of intellectual respectability; the very existence of, for instance, rule 8.9.2, governing how Flemish Dragoons in a brigade stack can be used during Rainy Weather scenarios, offered reassurance that you were not just some little kid saying “dooge.” Each game had scores of little square cardboard pieces representing military units, each bristling with coded information in tiny print: nationality, unit type, offensive and defensive combat strength, movement allowance, strength when disorganized, and so on. The units were deployed on hexagon-covered maps on scales ranging from a scattering of country villages to continents and empires.

I would disappear into these hex-gridded worlds for hours, days, at a time. I didn’t know anybody else who found war games appealing or even knew about them―other than Eric, a gentle night-walking insomniac my parents’ age who sometimes came over for Sunday dinner―so they were almost entirely a solitary pursuit, somewhere between reading a book and writing one. Playing both sides and preferring the stately symmetry of preliminary dispositions to the messiness of pitched battle, I could march and countermarch almost indefinitely, trying to outsmart myself. Serially re-contesting Guadalcanal or Austerlitz or the siege of Constantinople in nearly absolute solitude was like doing pushups with my imagination. Mostly, it built up my ability to do more pushups.

Check out the second part of “Ball Games and War Games” here and read part three here.

(Image credit: Amy Blechman.)