Journalist Charlie Hall offers a look into the art of making board games for the CIA. Acclaimed designer Volko Ruhnke shares a whole new meaning to the term “serious games” with him.

The United States intelligence community has a long history with gaming. Role-playing and simulations have been part of the Central Intelligence Agency’s best practices for generations, and are often conducted with the help of judges and mediators behind closed doors to explore complex, real-world situations.

But recently, the CIA revealed that they also use tabletop games—in effect, complex modern board games—to train its own analysts, and analysts from other agencies.

By day, Volko Ruhnke is an instructor at the CIA’s Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis. By night, Ruhnke is an acclaimed designer of commercial board games best known for the COIN Series, published by GMT Games. He said the CIA has been interested in tabletop games for a very long time, well before he started working there in the 1980s. Applying his knowhow in the commercial space to building games for CIA officers in a classroom setting was a natural fit. The goal, he explained, is to facilitate repetition in the practical application of intelligence gathering skills, about separating actionable information from noise and acting on it quickly.

Unlike commercial board games, Ruhnke’s projects at the CIA don’t need to be fun.

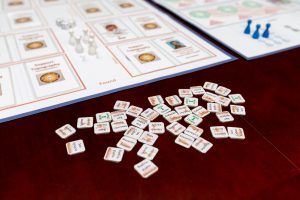

Ruhnke shared an example of his work, a project called Kingpin: The Hunt for El Chapo, which he co-designed with another instructor in the Defense Intelligence Agency. Kingpin uses the historical details of the capture of Sinaloa drug cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán as well as some fictional elements to create a challenging, asymmetrical game.

Kingpin is an adversarial game where one side plays the role of law enforcement and the other plays the role of Guzmán’s own handlers and associates. It revolves around hidden information, with each side playing on their own hidden game board behind a screen. El Chapo’s team is constantly moving around inside Mexico trying to evade the law, but the cartel leader has certain tastes and expectations. He’s not just willing to sit inside a hole somewhere, and one viable strategy is for law enforcement to use his proclivities against him. In the classroom, the game is played twice, with students taking turns playing on both sides of the table.

The key to the game, and to every other game played at the Kent School, is the facilitator. It’s their responsibility to keep things moving by interpreting the rules and feeding them to students on the fly. But in Kingpin, the facilitator also plays the role of referee. They have an important role in moving the action forward by revealing new information to both sides.

Unlike commercial board games, Ruhnke’s projects at the CIA don’t need to be fun. They also don’t need to support multiple playthroughs. In fact, they don’t even need to be played to completion.

“For a training game, it’s not nearly as important that you finish the game,” Ruhnke said. “It’s not even important that the game be balanced or have replay value. It might have those things. But our students are probably never going to play it again. It’s more about the insights and the process.”

Games are a very small fraction of what Kent School students will do in their coursework, but Ruhnke said the kind of hands-on work that tabletop gaming provides is invaluable.

Humans deal with complexity by forming mental models. . . . as instructors, we have to communicate those models to our students. Games do that very well.

“They are a tremendous tool for helping us prepare our understanding of complex affairs,” Ruhnke said. He likened it to studying the ongoing instability in Iraq and Afghanistan. “An insurgency is the interactions of many different actors, interests, tribes, forces, political movements, parties, village elders. It’s a complex compilation of factors, and that’s what we’re asking our analysts to understand. But human beings deal with complexity by forming mental models. So now, as instructors, we have to communicate those models to our students. Games do that very well.”

I was first introduced to the Ruhnke’s design work with a game called Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001 – ?, first published in 2010. In it, one player takes on the role of the United States while the other plays as Islamic jihadists. Each player takes actions by playing from a hand of cards that includes real-world, historical events. In one of my most memorable playthroughs the US prevailed only by keeping Benazir Bhutto alive long enough to drive the opposing player entirely out of Pakistan.

I asked Ruhnke about the potential conflicts that might arise between his commercial work and his classified work at the CIA.

“It is something that I have to watch,” he said. “I use my judgement in choosing to participate in work that’s outside of CIA work, and I’m not alone in that,” Ruhnke said. “I have . . . authorities here to double check. And in situation where I could have been exposed to sensitive information, I need to make sure that I’m okay here. That’s a routine procedure at the CIA. In my case, it happens to be that I’m making games, but if I were writing a book or writing an editorial in a newspaper it would be the same thing.”

The most gratifying part of the job for Ruhnke is in bringing intelligence officers together in a low-pressure environment in the same room with their peers. The Kent School isn’t just for members of the CIA, but provides instruction for analysts from the sixteen members of the United States Intelligence Community and all branches of the armed forces.

“It’s professionals coming together to practice their craft,” Ruhnke said, “separated from the immediate, pressing needs of our country. Of course, they’re interacting with each other every day, but in here it’s coming off the line, getting together as a brotherhood or a sisterhood of terrorism analysts. . . . I think it has to help.” ♦

(Image credit: Detail from Kingpin, a board game used by the CIA based on the capture of Mexican drug kingpin Joaquín Guzmán, popularly known as El Chapo. All images courtesy Central Intelligence Agency.)