Fiction writer Karen Russell’s visit to an aquarium unexpectedly reveals parallels between dolphins at play and the freedom of writing.

One uniquely perverse kind of movement is “play.” What could be a more audacious use of our time? Playgrounds are some of our most demented constructions, if you think about it—even more surreal, in their way, than cemeteries! Go to a playground, and what do you find? A do-nothing machine. A go-nowhere machine. The swing set, the see-saw. Human-powered pendulums that would appall Henry Ford. Here’s equipment that wheels in circles, going nowhere fast. Scaffolding to support kinetic dreaming. Stasis-in-motion. We set aside these nature preserves for the imagination; we stent a space for fantasy. Then we encourage kids to use a bunch of hot aluminum as the looms and struts for their waking hallucinations. No kid sees that rusty-ass equipment as we do: a bunch of lawsuits waiting to happen. They see: Spaceship. Gryphon’s nest. They see through, they see beyond. They do story-embroidery. Kids can see the symmetries, the underlying forms—and they play with them. A kid I am acquainted with saw the propeller on the back of a barge, and believed the boat was powered by a gigantic hair curler. Another saw a nun on television, and said with quiet conviction, “mermaid.”

Play may be how we consummate our humanness, but it’s certainly not unique to us.

Who knows what is actually happening to kids on a playground? Their real muscles contract; meantime, their names and their identities dissolve, reconstituting inside of some strange game. Play erupts on the threshold of the cognitive and the physical, the actual and the unreal. According to Friedrich Schiller, play cures our species’ “fragmentation of being” by reconciling the drive for form and the drive for sense, our longing to annul time and our desire for new horizons of truth and meaning. Why would anybody assume that this kind of movement is something gratuitous, or something to outgrow?

Play may be how we consummate our humanness, but it’s certainly not unique to us. Gregory Bateson has written about play in the animal kingdom. According to Bateson, play is the seedbed of language, all metacommunication. Take two wolves roughhousing. A certain kind of bite denotes “game on.” It moves them into a separate zone, marked off from ordinary time: a pageant of battle. This simulation constitutes a metacommunication between the wolves, says Bateson, because the play bite denotes a real one.

The value of play can’t be reduced to its effects.

“Now we are going to do a special theater of killing one another,” snarl the wolves. “This will be fun.” Their mock-battle makes possible a genuine encounter with ferocity, in the “safe,” cordoned-off arena of fiction.

Others will disagree with me, but I do not think the function of play is to build up muscle tissue or to discharge aggression. These things can and do happen, of course. But the value of play—like that cousin species of dreaming, reading—can’t be reduced to its effects.

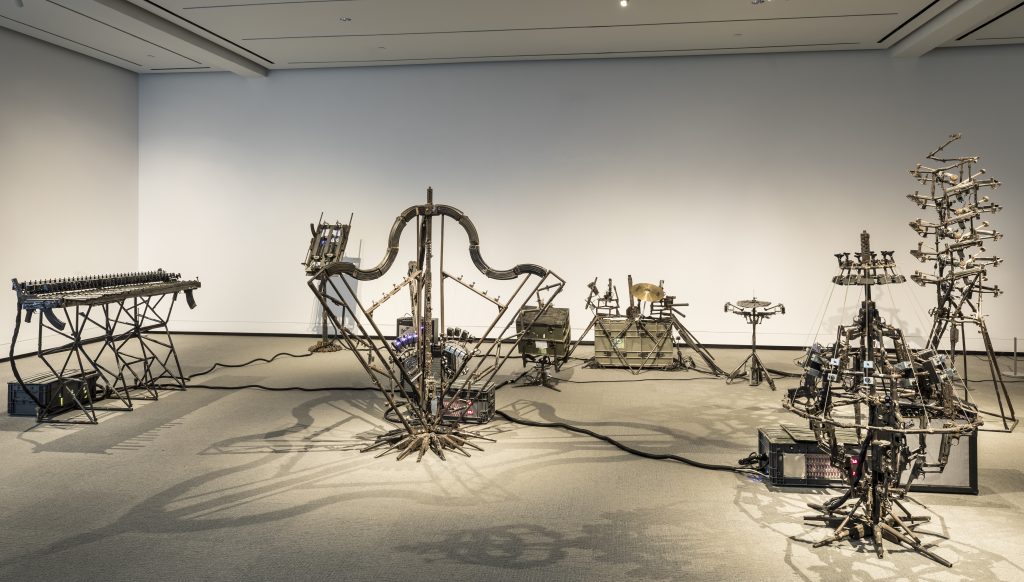

Play ceases to be play the second you hitch it to some utilitarian purpose. This is the paradox that challenges the game designers. It’s also the paradox that greets us writers at our desks, where it can feel truly insane to let yourself move through the dark, trying things out. It takes courage to move down the page without a definite goal, to discover through this searching process what remains to be said. It takes faith to make a not-for-profit movement, and it takes ingenuity and rigor to design the right structures to make play possible.

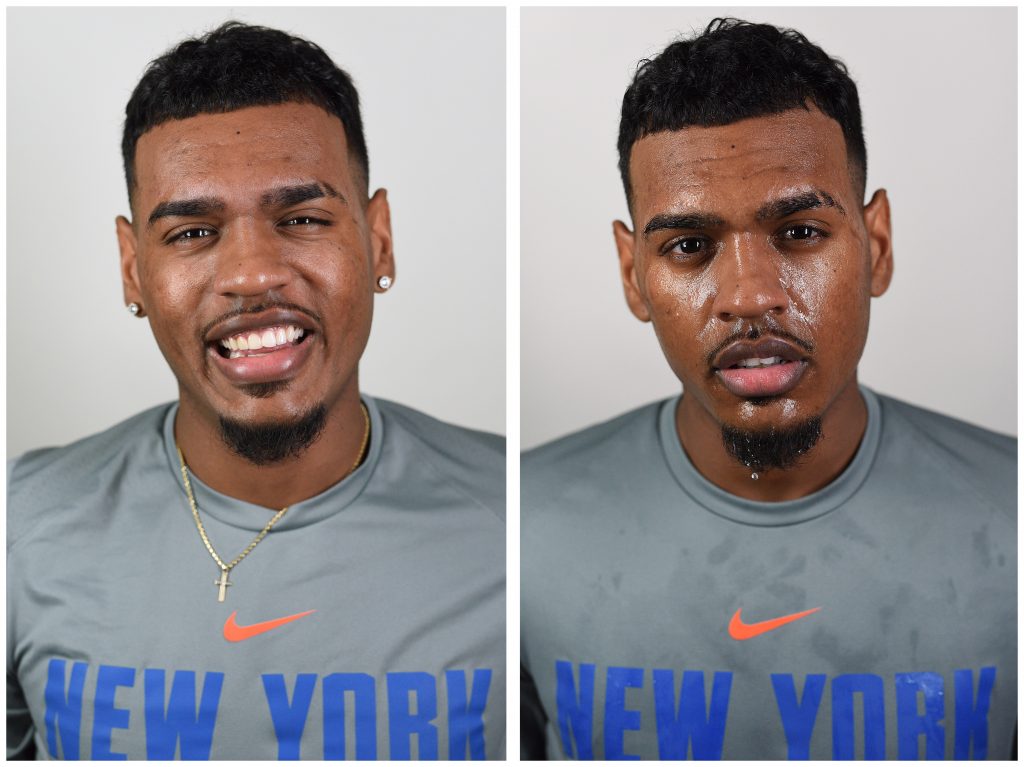

At the National Aquarium in Baltimore, I watched intelligent mammals playing, using their energy not for consumption or defense, but for creation. It looks like a game: they are making bubble rings. At Sea World, a dolphin figured out how to shape the bubbles, and now they teach each other how to do this; perhaps this is the dolphin’s bubble workshop. Evidently they take great pleasure in creating these elastic autobiographies. Artists of the moment, they watch the products of their bodies rise. Dolphins, I imagine, must also deal with survival questions, very important questions—the horizontal, linear ones, like, “Is there a shark behind that rock?” But they also design these bubble rings, each addressed by a unique sentience to the ocean’s surface. Up they rise, in shimmering flumes, for no reason, or for reasons that are as yet opaque to humans.

From where I was standing it looked like the animals were enjoying a radical freedom.

Viewed from a survivalist’s standpoint, the dolphin’s playful undulance seemed like a pretty dubious use of calories. In Schiller’s terms, they are “burning up their surplus.” Goofing around, where they could be mating or hunting or conserving strength. If they were our cousins, we might tell these dolphins to get a haircut and get a real job.

From another angle, however—from where I was standing, outside the tank—it looked like the animals were enjoying a radical freedom. They were reveling; they were revealing something hidden inside themselves, to themselves, in the form of these bubble chains. In a state of play with no clear goals, they were turning themselves inside out, discovering what a breath could become. And I have to confess, I was so moved by this. It was hard not to read into their fluid ricochet, something analogous to the free play of thought.

Jokes and dreams and games may be the only places—and I mean to evoke a physical place, a site—where a certain kind of truth telling is possible. Some of the best lines in our literature occur as parentheticals, asides. Shakespeare’s fools and ghosts murmur truths that would be otherwise inadmissible in any king’s court. This playfulness must pose a double threat to authorities; the second they take such writing seriously, they risk looking ridiculous themselves.

It’s simplistic to reduce a writer’s playfulness to a tactic, a device.

Critiques of human monstrosity get encoded in fables about pigs and overcoats and Yiddish demons. But these writers also joke for joking’s sake. It’s too simplistic, I think, to reduce their playfulness to a tactic, a device. The human exuberance and irrepressible strangeness of their books is an implicit critique of global monoculture and local tyranny; these authors resist the homogenizing, dehumanizing forces on their own terms. Such writing waves a freak flag, signals a freewheeling intelligence. It says: we are free to move down the page, regardless of our physical circumstances. You can shut down the roads, control the news, imprison our bodies, deluge us continuously with reasons for paralyzing fear, and still we can move invisibly in that other territory. In these writers’ hands, play becomes a celebration or everybody’s upward mobility, where the imagination is concerned.

It can be a revolutionary act, to take the scenic route.

I love being reminded that no matter what we are writing, we are playing with sound, patterning music for another’s mind. And that once you find the rhythm of a piece, that music can tug you irresistibly toward sense. I wanted to write about this topic in no small part because play hasn’t felt safe to me for a while, and that scares me. You have to fight to preserve a space to wander, where movement is its own reward. I don’t mean to sound naive here—groping in the dark can also feel totally miserable. Our fun is not everybody’s fun. Play is a risky use of resources, it is a waste of time, if you demand that it deliver a payoff.

“Dolphins play to test the contingencies of their world,” I was told. And so do we. ♦

(This piece is a condensed and edited version of the 2015 AWP Conference & Bookfair keynote address by Karen Russell. Used with permission from the Association of Writers & Writing Programs. Image credit: Photo by Mathias Appel from Flickr.)