Artist and archive hound Marc Fischer digs deep to find the un-fun side of play and games.

Industry trade periodicals represent a vast layer of publishing that lives outside of even the best magazine racks and news stands. In Chicago, where I live, our city’s main public library, the Harold Washington Library Center, has a rich browsing collection of these business magazines, with some dating back to the late 1800s. The library’s holdings reveal that there is a magazine for just about any trade or industry you can think of. Rubber World, Quick Frozen Foods, Gifts and Decorative Accessories, Scrap, Battery Man, American Shoemaker, and Institutions Volume Feeding are just some of the titles on offer.

While working on an ongoing publication series titled Library Excavations, I became particularly fascinated with the magazine Playthings, which describes itself as “The Toy Business Authority since 1903.” For a magazine about the business of toys and play, Playthings usually isn’t very fun. Its columnists are generally serious-looking older white men whose portrait photos head off columns about sales trends, rising and falling interest in particular types of toys, supply chain dilemmas, production problems, and seasonal expectations for key shopping periods like Christmas, Halloween, and the arrival of summer. Sometimes there is a column about how great Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles are doing in the market, and then maybe another about how they are no longer doing so well. A long winter with late snow in Chicago, we learn, will screw up toy sales in the spring and delay profits.

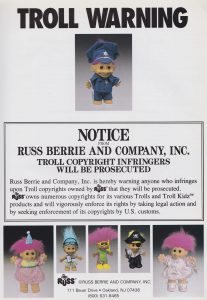

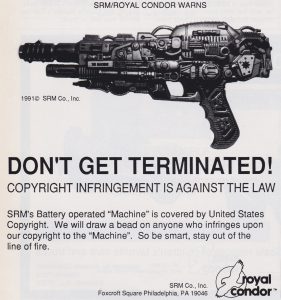

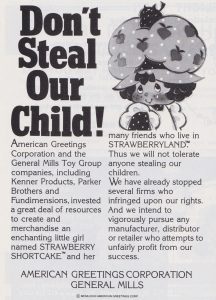

For this layperson, the most interesting feature in Playthings is not the content written by the magazine staff, but the legal notices placed by toy manufactures. It is here, unexpectedly, that the real play happens–though always with a hefty element of threat and sometimes more than a little menace. Having gone to the trouble to create Strawberry Shortcake, Trolls, and Super Soakers, corporations are not about to play around when it comes to competitor knock offs.

In a July 1992 editorial, Playthings editor Frank Raysen Jr. writes: “Unfortunately with its faddish nature, the toy industry is particularly prone to the copycat syndrome, as infringers seek to capitalize on the latest hits before the next one comes along. It’s a problem that never seems to go away, despite the best efforts of U.S. toymakers, the Customs Service, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission. And it’s a costly problem to combat with threatening ads, lawsuits, or other preventive measures.”

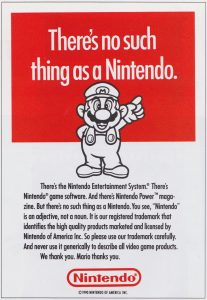

Hairs are split ever so finely in these notices. A 1977 notice for Marx Toys, makers of the Big Wheel tricycle, calls out another manufacturer that had the chutzpah to also describe their tricycle as “big.” A notice placed by Nintendo uses their game character Mario to implore the industry to use their company’s trademark properly. There is no such thing as “a Nintendo.” There is the Nintendo Entertainment System® and Nintendo Magazine®, but you should not get all generic with their trademarks and apply them indiscriminately to all video game products.

Most of these notices engage the reader in a couple ways. First, the companies want to remind everyone that they make things that are fun, so clever wordplay is a must. Second, they will not hesitate to sue you into the ground if you steal their stuff. There is a compelling friction created when these mixed goals rub against the enjoyable memories readers may have of playing with toys that are caught in the middle of a legal battle. There is an unexpected joy in coming across these notices at the odd intersection of childhood fun and corporate legal antics. ♦

(Image credits: Photo of advertisements from the defunct trade magazine Playthings by and courtesy of Marc Fischer.)