Lydia Gordon, assistant curator at PEM, pays a visit to the studio of artist Derrick Adams and considers the racial politics of play and the pool.

On a recent research visit to New York City, I had the privilege of sitting down with multidisciplinary artist Derrick Adams in his Brooklyn studio alongside PEM’s Curator of the Present Tense Trevor Smith and George Putnam Curator of American Art Austen Barron Bailly. Adams is finishing up a body of work that depicts black bodies in water: figures relaxing on floats, embracing each other, and playing. Using a brilliant mix of warm and cool colors, Adams deconstructs his subjects into collages: a figure’s arm is a different hue than her leg, one’s cheek is a different color than his nose, and their swimsuit patterns stand in vivid contrast to their deep turquoise environment. While the treatment of color and flatness of paint initially captures one’s attention, it is the content of Adams’ series that begs further thought. What are the politics surrounding representations of leisure and the black figure?

Representations of the figure in states of leisure are not new to the history of art. We can trace representations of recreation and leisure to the art-making of ancient civilizations, including Egyptian, Roman, Greek, and Assyrian. But in modern Western societies, the practice of leisure became an arena of racial, class, and gender divisions alongside the development of cities and growing populations. Particularly after the French Revolution, it was only the bourgeoisie who had regular access to the parks, cafes, and operas, while the working class had free time only on Sundays. This imbalance and the mundane ambivalence associated with bourgeois leisure activity is captured in many of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works of European artists, such as Mary Cassatt (born in the U.S., lived and worked in France), Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The representation of figures swimming was also a worthy subject of art, and made popular by Renoir, Gustave Courbet, Viggo Johansen, as well as American Impressionists, including Childe Hassam. To this day, artists take inspiration from the figure aswim, such as British artist David Hockney whose work on this subject is arguably his most iconic. Yet, all of these canonical examples fail to depict a figure who is not white. Where do we find representations of black figures swimming—at leisure at all—in art and why has it taken so long?

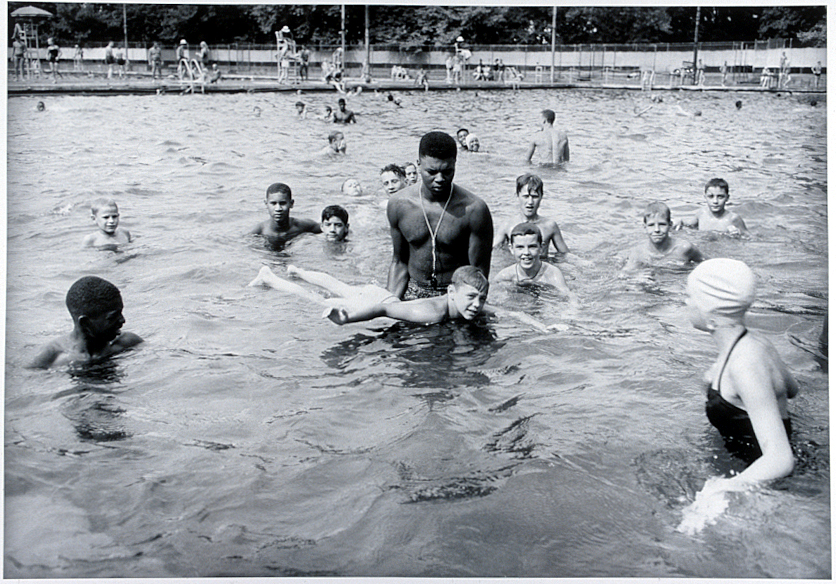

A recent exhibition at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, in Lincoln, Massachusetts, called Bodies in Water, explored representations of the human relationship to water. The wall label that accompanied Charlie “Teenie” Harris’s Swimming Instruction at Integrated Pool (1959) explained how most public pools in the U.S. were segregated until the 1950s, and almost no pools were built in black communities in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. When African Americans did have access to pools, they were small and insufficient compared to the grand resort-style pools built in white communities. In places with racial segregation policies (whether official or community-policed), swimming pools became sites of extreme violence and oppression against black children and patrons. The effects of this racial injustice and oppressive site continue to plague our society: seventy percent of black Americans do not know how to swim.

Harris’s photograph presents an uncommon image: a black lifeguard giving a swimming lesson to a white student in a 1950s integrated pool. While Swimming Instruction shows no immediate conflict, the story behind the image perseveres: the Highland Park community members and city officials resisted integration of Pittsburgh’s public pools through 1951. It was only the threat of legal action that forced the city to pass non-discrimination laws at swimming pools and to hire black lifeguards. While the central figure in Harris’s photograph is unknown, we understand he is giving more than just a swimming lesson. At the time, an image of a black lifeguard in a position of authority was a political one: the boy is responsible for not only for his student’s safety, but he is also seemingly risking his own well-being against a backdrop of very recent oppressive and violent actions that occurred at his very site of employment. Swimming Instruction at Integrated Pool represents the racial politics of staying afloat.

Considering this history of swimming pools as inaccessible sites of leisure for black Americans, Derrick Adams, like Harris, carefully selects which scenes to signify. By depicting his subjects in reclined and relaxed positions, Adams’s work confronts this legacy with optimism and ease. His subjects take the place of white America’s (read: Taylor Swift’s) obsession with swan floats and flourish, many of them seemingly posing for their own close-up. And it’s about time. Adams’s figures are so diligently rendered that the paintings serve as portraits as much as they do to capture a scene. His representations of black bodies swimming and floating work to insert a kind of humanity within a long trajectory of everyday subject matter and the omission of black figures within it. It is through this lens of being and belonging that Adams’s art creates new ways of understanding sites of leisure as not only raced and privileged, but also optimistic and playful.

(Image credit: Derrick Adams, Floater No. 58 (two rafts), 2017, courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery.)