Narrative designer Cara Ellison untangles the not-so-subtle distinctions between those who design games and those who design the narratives that drive them.

I design stories for video games. Some people think this means I’m the person who writes the line, Oh my god we’ve got to get out of here! Some studios still believe that this is all I should do: “Isn’t that what scriptwriters do? They write what characters say.”

But “narrative designers” have a broader remit. First we decide on the themes, the core motivation for telling a story, the politics of it. Then we create characters around those themes. Then comes the three-act structure: how the characters may change, and the minuscule plot details that lead you to a satisfying ending. Then, and only then, do you get to the dialogue. Slicing up the story so that it becomes a series of delicious, escalating, conflict-driven scenes (this is also how “branching narrative” is developed in games) is one of the hardest parts of the job. You decide what to show and how to make it the most interesting thing to show.

Most of this planning, this discussion, this detail work is the invisible part of the writing. Most people think that when someone sits down to make a story that it’s just as I am doing now: typing words into screenwriting software. But there are hours and hours of note taking, an agonizing amount of media consumption, standing in the shower, sitting in meeting rooms or cafes (notebook and pencil in hand), cursing and raging, and trying to entice a writing partner. Before you can begin writing the very first scene in a drama, many hair-pulling hours have been spent wondering if that scene will be worth the thousands of dollars that will be spent on making it to the screen. And that’s before even the first executive reads it (and probably hates it).

Each player becomes a performer of verbs within the virtual space.

Designing stories for video games is complicated further by one particular thing: the verb. Video games have a lot in common with theater and improv. The game designer creates a virtual space in which each player becomes a performer of verbs within that virtual space. The narrative designer’s job is not just to decide what is shown, as in film, but what it means that you can experience specific interactions. A film director may control what you are seeing and hearing at all times. But in games it is the set of verbs, or what labor you can do, that tells the story. It is the experience of what doing is available that tells the player who their character is, what their purpose is, and most importantly, gives them the experience of story. It’s perhaps the most empiricist of all mediums.

That a game’s story power comes from the verb is still controversial in games because a “game designer” and a “narrative designer” are not always the same person. When they are, the game has a better chance of being nuanced and meaningful. Yet game designers often are employed to undertake the considerable mechanical work of constructing the video game verb’s execution, while the narrative designer is supposed to give those verbs emotional resonance. This may not make sense to people outside of video games: Why isn’t the narrative designer directly constructing the mechanical production of narrative?

Unfortunately it has a lot to do with the separation of sciences and humanities in schools: the idea that tech or science know-how is for introvert non-fiction-reading, math-nerd men, while the humanities is for feelings-junkies and Austen-reading “girls.” This self-fulfilling prophecy, and a lack of a balanced education on both sides (a combination of communication, ethics, and literacy in the sciences, and tech literacy in the humanities) has hamstrung us. To look at blockbuster video games (and tech products like Twitter) is to recognize that few people in tech are schooled in the complicated Big Themes of Empathy and Communication, or in how to produce caring and nuanced people-friendly systems. This is often the result of a university system that proselytizes Product Innovation, Novelty, and the Free Market as king. Game developers are so overworked that by the time they get into the business with their hard-fought tech skills they have no time to sleep, never mind read Nabokov and contemplate theories of conflict resolution. And for the large part good storytellers are fantastically frightened of technology: when you’re already poor, taking two years to learn how to program is out of the question. So we two are stuck on the verb, and we have to work together, often with different creative languages.

If you cannot tell what the story is saying without sound or text, someone has failed as a storyteller.

As my technical skills in game design have leapt forward, one of the biggest realizations I have had is this: much like how animators or comics writers regard successful storytelling, it’s all in the action.If you cannot tell what the story is saying in a 3D game without voiceover or text, someone has failed as a storyteller. One of the best pieces of comics craft advice is: write each panel as if there were absolutely no dialogue. With just a glance at the page, the reader should know exactly what is happening and how the characters feel about it.

To implement this theory in a game, a narrative designer has to constantly pitch to her colleagues: the environment artists, the animators, the game designers, the audio designers, sometimes even the coders who determine the transition speeds and frequency of behaviors in-game. And these days I find myself more and more pitching to the team that we might consider having no dialogue at all. What if I design a story that needs no words? How can we do that well? What about using silence here? Isn’t that more powerful than being overloaded with sound and chit-chat?

We design for what the player can see or hear.

Some developers are incredulous at this coming from a job title they associate with screenwriting. But the advantage is that I am usually not asked to “fix” gameplay by having an obtuse piece of dialogue explain how to solve a puzzle, or how to connect A to B, or cover up a plot hole. We are forced to design so that mistakes cannot be made like this. We design for what the player can see or hear. There is less room for “Ah, Cara will fix it” (although, I still do fix things with story, plot, and character appearance). I sometimes glibly remark that I want to make my own job obsolete: the less dialogue the better the game is. But that’s me playing into my own complaint: narrative design isn’t just writing. It’s communicating in every form possible so that the natural output is that someone somewhere feels a connection to the material. After all, when we watch someone touch a loved one’s face, we don’t have to hear them say “I love you” to know that the action itself distills all the meaning we need. Now all we need to do is design a game capable of that gentle verb. ♦

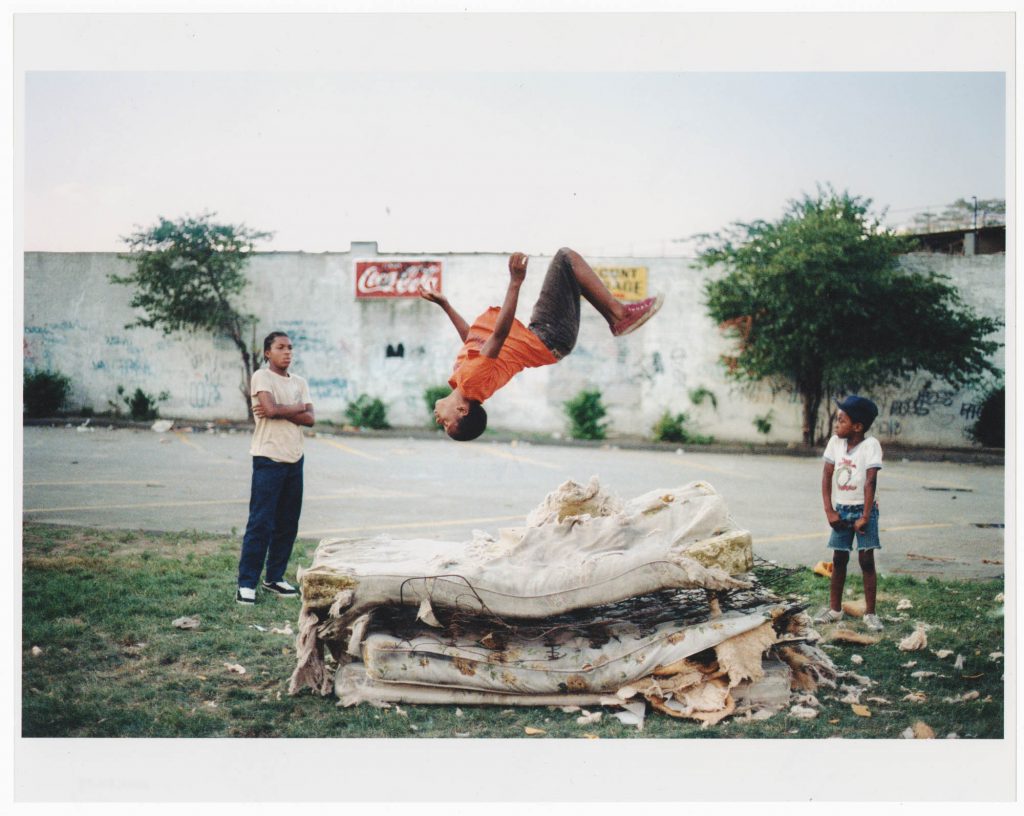

Photo credit: Image from caraellison.co.uk. Courtesy the author.

PLAY reinvents the rules.