In the first segment of a two-part essay, Owen Hatherley looks back on the signal gallery of his youth and the birth of “fun” and “entertainment” in the white cube.

Every now and again, I visit the municipal art gallery in the English port city where I grew up. I won’t name it, because it could be pretty much anywhere in north-west Europe, and definitely in any provincial city in Britain—this is not a specific story. Placed in a town that had otherwise staked its post-industrial future on gigantic retail parks and malls, it was a highly unusual space. Part of a sprawling Civic Centre built in the 1930s, clad in pale and icy Portland stone, you entered it through a stripped classical entranceway and walked up a flight of steps to a wide, vaulted space. One of the things that can give you shivers down the spine is the sudden emptiness and quiet, the sense of space and graciousness, almost weightless. After its foundation in the 1930s, the gallery’s curators and its backers at the Labour-controlled City Council enlisted the upper class art historian and head of the National Gallery Kenneth Clark to advise on their purchases. By the 1990s, when I first started visiting the City Art Gallery regularly, that collection had just a little bit from each era. One Renoir painting (of a man, disappointingly for adolescent visitors). One Rodin statue. One Quatrocento altarpiece, one Renaissance painting, and one baroque painting all placed facing each other in one darkened room. One William Blake watercolor. When you came to the modern art, it specialized in work that was, in the 1990s, extremely unfashionable—the seedy London scenes of the Euston Road group, the aggressive industrial modernism of the Vorticists, the apocalypses of Stanley Spencer, the post-Constructivist abstraction of the systems group—nary an unmade bed, a light switching on and off, or a pickled animal to be found. Instead there was a high seriousness, with an assumption throughout that this was a place you were meant to spend time in, and get lost in. It was not meant to be fun. It was meant to take time. Nothing was explained, merely captioned. It didn’t get many visitors.

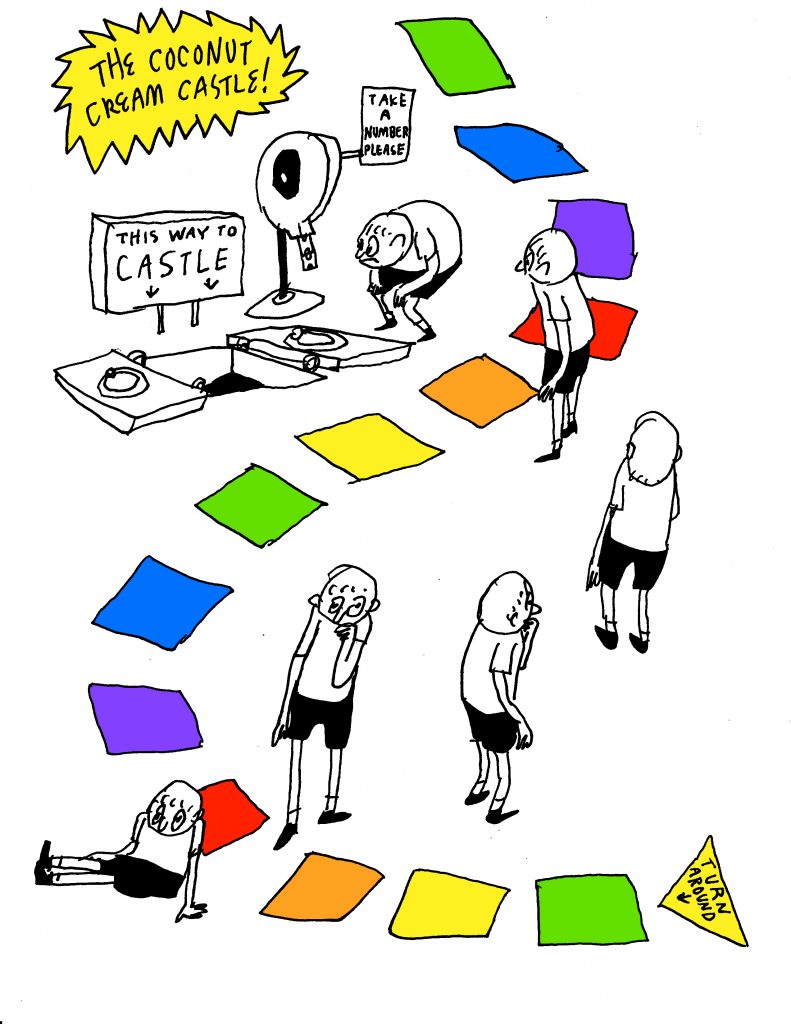

There was—still is—one exception to this rule, one little piece of play in among all of these intricate, moody, adult canvases. It’s a work by the Czech sculptor and animator, and perhaps appropriately, it doubled as a (perhaps not incredibly successful) generator of revenue. Placed in a glass box was a wooden head and a complex series of pulleys, gears and wheels. You would put in a coin—a note cello-taped to the contraption tells you not to drop in anything larger than a two pence piece—and the mechanism would start working, and the odd little head, one part phrenology aid and one part surrealist sculpture, would chomp away at your gift to the municipal Art Gallery. It seems in anachronistic retrospect a little like a parody of the way that art has come to be seen—you pays your money, you watches a little play, you interacts, you goes home.

There was a high seriousness; that this was a place to spend time and get lost in. It was not meant to be fun.

Except, when the thing was installed, that can’t have had much to do with the sort of art gallery this was. It was a strange self-referential toy, and for around ten years, it sat in the corner of the great vaulted hall, its mechanism broken, unable to take any money at all. At the same time, the City Council, undergoing a mercifully brief period of Conservative control, was trying to plug a hole in its finances, partly produced by funneling cash into an interactive exhibition aimed at children on the subject of the Titanic (it sailed from the port nearby), by selling off artworks from the collection—the Rodin Eve, and a bafflingly collectible equestrian painting. This was ruled illegal, but the collection was dumbed down nonetheless, and temporary exhibitions nosedived in seriousness. An exhibition of third rate Warhol offcuts, which contained a room supplied with wigs and leopard-skin jackets that you could get yourself dressed up in, was the least bad of these—exhibitions on Animals in Art and (no, really) Fairies aimed to get in the punters. Only last year was the collection reorganized properly and in a nice, optimistic gesture, the Czech mechanism was fixed, and takes loose change once again.

The problems this Gallery has faced seem indissolubly linked to the sort of institution it was imagined to be in the 1930s. Reflecting the historical Labour movement’s uneasy alliance of “class-conscious” and educationally-minded workers with patrician, intelligentsia thinkers, the Gallery was meant to be the finest things, available for free, to anyone and everyone, funded not through sales of works or ticket purchases or anything other than taxation and the occasional Arts Council grant. The lack of explanation came with that—it was assumed that once all the good things had been assembled and laid out for the worker to see, he or she would be able to understand what was happening, and would respond with intelligence, distance, and respect, because they had been treated in the same way. In that, it reflects the model of artistic enjoyment set up by its famous adviser. There is no “play” or “interaction” in Clark’s TV series Civilisation. When Sir Kenneth Clark strides through the castles and palaces and historic cities in Italy and France (so distant from this city, with all its malls! You would never think the city was a historic medieval port), he has on his snaggle-toothed face a look of calm and ironical consideration, of detached disinterest that doesn’t preclude an occasional moral disgust (at slavery, at the industrial revolution, at all that is bellicose and “uncivilized,” like the Vikings, however elegant the design of their ships). That light and floating walk that he does through these places is the kind of movement you are expected to make when walking through the City Art Gallery—only, unlike Clark, you aren’t meant to touch the art, not expected to run your fingers along the contours of the paintwork, to grope the Henry Moore sculpture—he owns that Moore and can touch it, we own that Rodin, and can’t. Even the little head in its box is under glass, and can be touched only by your penny, not your fingers.

Like many of Bourriaud’s ideas, it is seductive precisely because it appears to resist the atomization symbolized by all of those strip malls and motorways, cutting across the city just yards from the City Art Gallery.

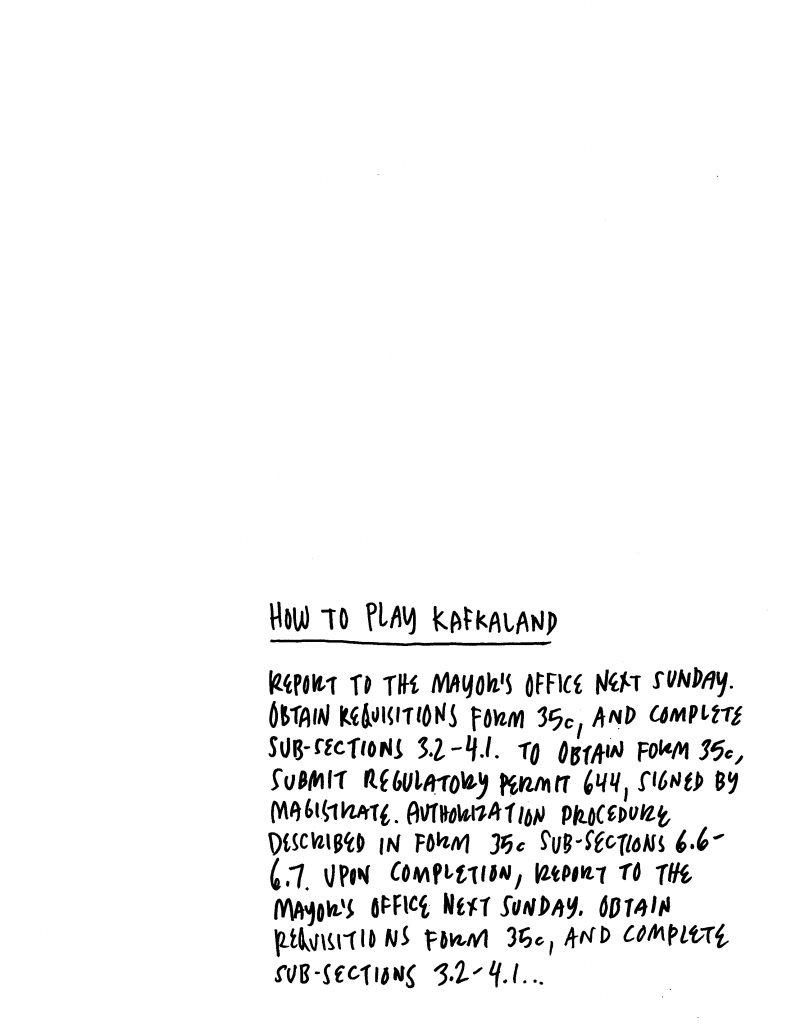

If the work of the 1990s, so conspicuously absent from the City Art Gallery, however “shocking” its content, remained at the level of objects to be looked at and not touched—to be “engaged” with using only the mind—the City Art Gallery would seem to be equally out of place with the new paradigm developed in the 2000s, by Nicholas Bourriaud and his stable of artists; the world of Relational Aesthetics. Whereas the City Art Gallery considered that individual members of a community would come and visit their treasures, Relational Aesthetics was all about establishing what a community was, or trying to create it, as if in acknowledgement that this endeavor had been a failure. So these were works you could play with, sift through, and that would come to you, rather than you coming to it. An artist would turn up in your “community,” and play you some tunes, serve you some dinner, do a little dance for you. Like many of Bourriaud’s ideas, it is seductive precisely because it appears to resist the atomization symbolized by all of those strip malls and motorways, cutting across the city just yards from the City Art Gallery. It wants to bring people together. Of course, the majority of the people who are consuming the art are not those in the community in the first instance, but as with much recent experimental art, merely watching it after the fact, on a video in a white-walled room, with the only remnant of the warmth and conviviality originally promised being the softness of the beanbag you’re sitting on to consume the work. ♦

Part two of “New Babylon” will appear next week.

(Image credit: Photo courtesy Nochn Nordlicht via Flickr.)