When it comes to brain development, we know play is essential. But what kind of play and how? Neuroscientist Sergio Pellis goes in depth on how the brain produces play and how we—and our animal counterparts—benefit from playful engagement.

What makes play play? Many of the actions performed during play are the same as those performed in non-playful situations, yet we are often able to recognize intuitively the playful version as play. A year-old infant may swing a hammer, but compared to an adult, their prowess is clumsy, misdirected, and ineffective. Given that we mostly associate play with young animals, what we regard as “play” may simply be an artifact of immaturity. The problem is that “play” looks playful even when adults are performing the actions that we perceive as playful. Consider adult Japanese monkeys collecting stones, then banging them on the ground, rubbing them together, throwing them in the air, and so on. They look no different to the same actions performed with stones by immature monkeys (figure 1). There is something about playful engagement that is distinctive.

Long-time play researcher Gordon Burghardt puzzled over this problem for years and eventually pulled together all the elements that different observers had noted into a cohesive framework. According to Burghardt, for a behavior to be considered as play, five criteria need to be met.1 For example, consider the difference in the actions of a young child using a spoon to feed himself/herself versus when he/she is using a spoon playfully. When eating, the spoon is used to pick up food and deliver it to the mouth, so that the actions are clearly functional in relation to ingesting food. In contrast, the same actions when performed in play may not lead to such a functional outcome; rather, the spoon may be used to pick up food or some other item, but then, as it is brought to the mouth, may be flung past the right ear. That is, the actions in play are incompletely functional in the context expressed (criterion 1). When eating, the movements are adjusted to facilitate delivery of food to the mouth, as the ingestion of food is what rewards the actions.

In contrast, during play, the lifting, moving and flinging of the spoon are rewards onto themselves. That is, the actions in play are performed voluntarily and are self-rewarding (criterion 2). When eating, the successful delivery of food from plate to mouth constrains how the spoon can be moved. In contrast, during play, the spoon can be moved willy-nilly. That is, the movements are modified from how they are performed in the functional context (criterion 3). When eating, movements that are rewarded by a successful outcome—such as picking up food or bringing food to the mouth—may be repeated over and over as long as the food lasts or the child remains hungry. In contrast, during play, movements that are irrelevant to any such functional outcome, such as flinging the spoon past the right ear, may be repeated again and again, although the speed and exact trajectory may vary from case to case. That is, during play, movements may be performed repeatedly, but not necessarily in an invariant form (criterion 4). Finally, when eating, especially if the child is very hungry, or offered food they like very much, a sudden noise may have little effect other than cause a momentary distraction. In contrast, during play, a sudden noise or some other scary intrusion may lead to a complete cessation of the play and hunger is likely to lead to seeking food rather than for opportunities to play. That is, play is initiated and maintained when the subject is healthy, relatively unstressed and in a secure environment (criterion 5).

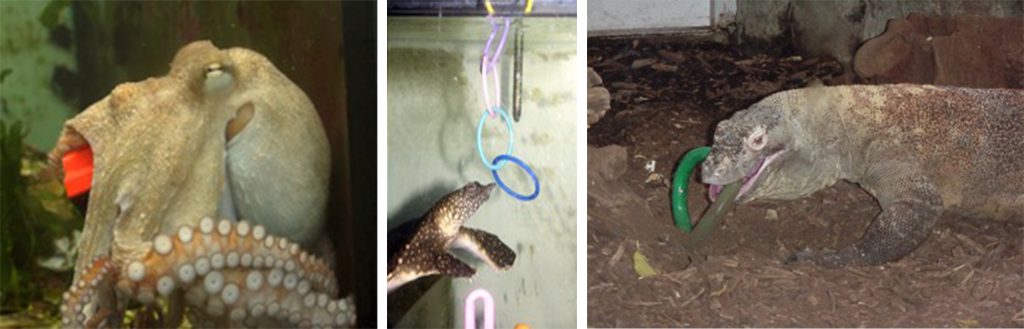

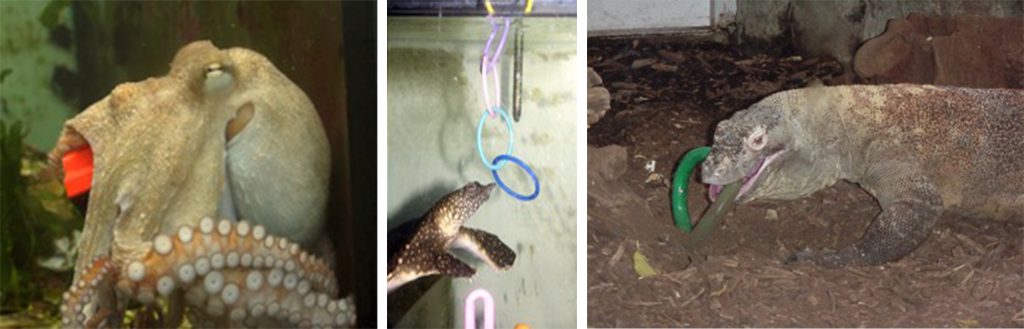

This criterion-based definition of play has had some revolutionary consequences. the most dramatic of which has been to find that not only the mammals with which we are most familiar, such as dogs, cats, monkeys, and, of course, people, can produce behavior that fulfill these criteria, but also some birds, reptiles, fish, insects, and octopus do (figures 2, 3, and 4). Across a diverse range of species on the tree of life that encompasses the Animal Kingdom, nature has thrown up animals that can produce the qualitatively distinctive behavior that can be recognized as play.

This drags us away from our self-centered view of play—a property of humans and some other animals that are human-like—to one recognizing that play is a recurrent feature of life more generally. Another consequence of Burghardt’s definition is that it makes clear that play is not about what is done, but how it is done! This ‘doing’ side of play becomes most glaringly evident in its social expressions, such as when two young children playfully wrestle one another to ground. ‘Rough-and-tumble’ play like this exaggerates the actions performed, ensuring that the partner perceives them as playful. How this is achieved has been well documented in non-human animals.

Rough-and-tumble play

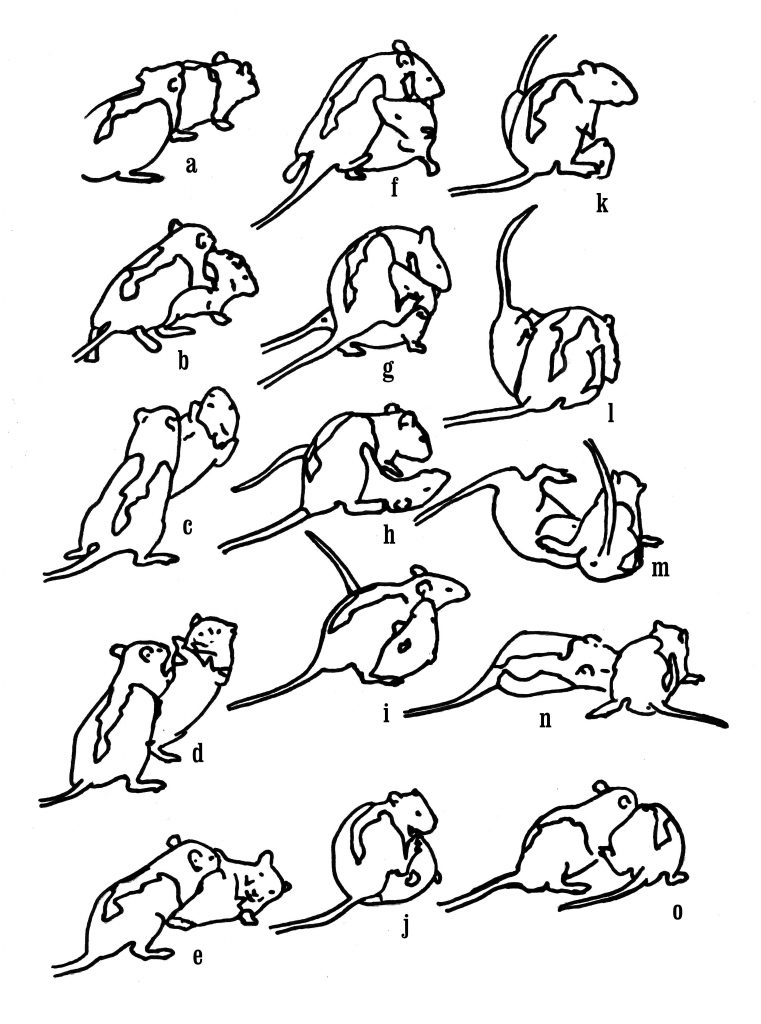

One of the most common forms of social play in the Animal Kingdom is rough-and-tumble play or play fighting. In such play, partners may compete to bite one another, as in aggression, or mount or groom one another as in sex and social bonding. The playful versions of such encounters can be distinguished by the rules that govern the actions that are strung together. During the initial phases of sexual encounters the male attempts to nuzzle the female’s nape as a prelude to mounting and copulating. Now consider two rats engaging in play fighting. They too compete for access to the nape of their partner’s neck, which if contacted is gently nuzzled with the snout. The same actions occur during the initial phases of sexual encounters when the male attempts to nuzzle the female’s nape. In play fights, the competition for the nape is repeated, often to exhaustion, without ever leading to copulation. Thus, while the rules for mating allow a copulatory ending, those for play fighting do not. We can derive further rules of play by considering the dynamics of an actual interaction between two rats.

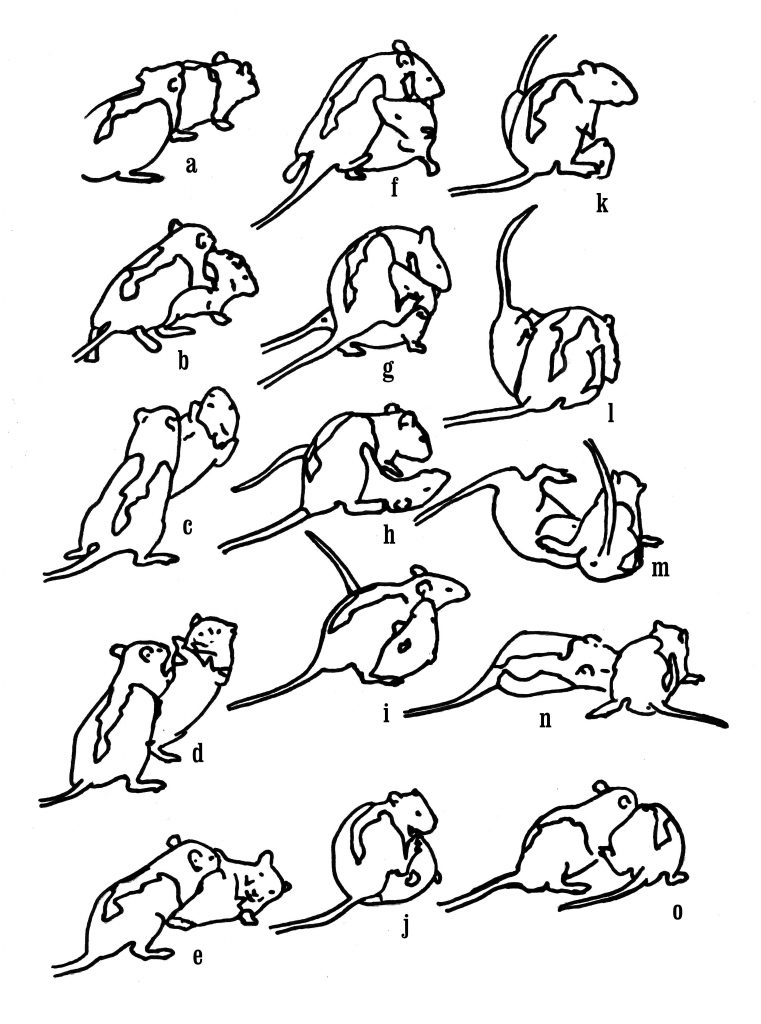

Two juvenile male rats are shown engaging in a play fight in figure 5 starting with the rat on the left approaching from the rear (a) and pouncing towards the nape of its partner’s neck (b).2 However, before contact is made, the defender rotates around the longitudinal axis of its body (c) to face its attacker (d). As the attacker moves forward, the defender is pushed onto its side (e), but then rolls over onto its back as the attacker continues to reach for its nape (f–h). From the supine position, the defender launches an attack towards its partner’s nape (i), but is blocked by its partner’s hind foot (j, k). Following another attempt to gain access to its partner’s nape, the rat on top is pushed off (l) by the supine animal’s hind feet (m), which thus enables the original defender to regain its footing (n) and lunge to attack its partner’s nape (o).

Two important facts about play fighting emerge from this sequence, a sequence that is mirrored in the play of a diversity of animals, from wasps, parrots, dogs, and monkeys to people. First, note that the rats are actively countering attacks with defensive maneuvers. That is, they are actively competing to gain access to the play target, in this case, the nape. Second, the rat that was initially attacked eventually manages to push off its attacker, and launch its own attack. That is, there is a role reversal. Unlike serious fighting, during play fighting, not only are the animals competing, but they are also cooperating. Sometimes the cooperation present in play fighting, which facilitates role reversals, can be very dramatic.

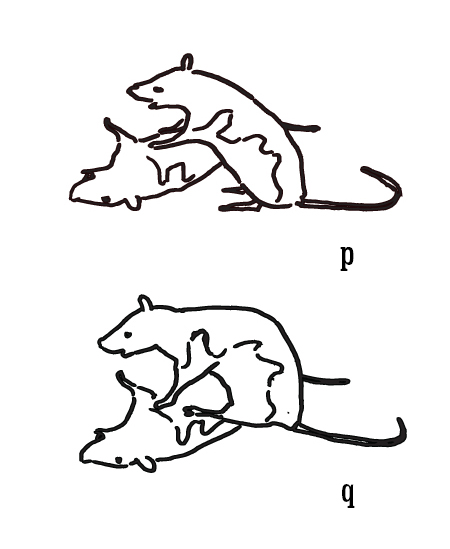

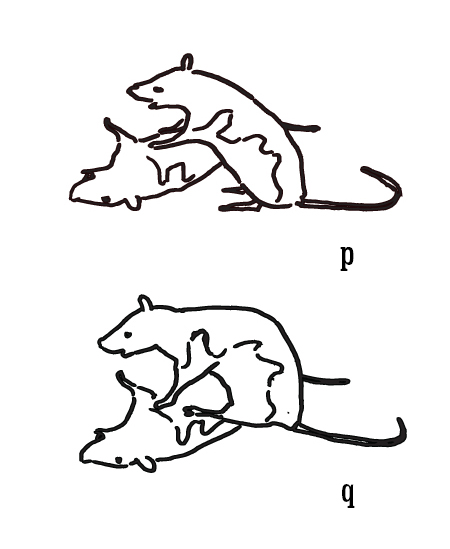

Although there are species differences in how cooperation is injected into play, it is a necessary element of engaging in play. In the rat, the obvious advantage for one partner standing on top of its supine partner is that it can use its paws to restrain the movements of its partner and so block counterattacks (see f–k in figure 5). In order to use its forepaws effectively, and to make any necessary, accompanying shifts of body weight with its upper trunk, the rat on top stands with at least one of its hind feet on the ground; this provides a solid base of support for its upper body movements. By anchoring its body weight on its hind feet, the rat standing on top has considerable stability and so can maintain a high degree of control over both its own movements and those of its supine partner. However, rats will sometimes do something seemingly stupid when on top during play: they stand on their supine partners with all four of their limbs (figure 6).3 When they do this, they have less control over their own movements, and a reduced ability to restrain their partner’s movements. Indeed, role reversals skyrocket from thirty percent when in the anchored position to over seventy percent when in the unanchored position. That is, the rat with the advantage handicaps itself, making it easier for its play partner to gain the upper hand. There are species differences in how cooperation is injected into play, but without some way of injecting a cooperative aspect into playful interactions, they fall apart.

Recall your own childhood experiences. Imagine engaging in play fighting with a partner that always gains the upper hand, or one that you always dominate – both are boring play partners. A partner over whom you can gain the advantage—at least sometimes—and who makes it a challenge to do so, provides a much more satisfying experience, an experience worth repeating again and again. For example, my only brother is six years older than me so that when I was at the height of eagerness to engage in play fighting, between eight and eleven years old, he was already past it. Moreover, he was bigger and stronger so most of my attempts to engage him in play were rebuffed or ended with me being pinned to the ground. Not much fun! Still, he wasn’t past the occasional fun wrestle so, on occasion, not only did he respond to my overtures, but he let me gain the advantage, even if only momentarily. The allure of an occasional play fight, and one that I had at least an outside chance of winning kept me coming back for more. Even though most attempts ended in the same way, the fact that any particular instance did not have a predictable outcome, made continued attempts to play with my brother all the more exciting. In this regard, I am no different to the rats and other animals discussed earlier. It is the assurance of a well-rehearsed routine interspersed with the frisant of unpredictability that makes play enjoyable.

How the brain produces play and how the brain benefits from play

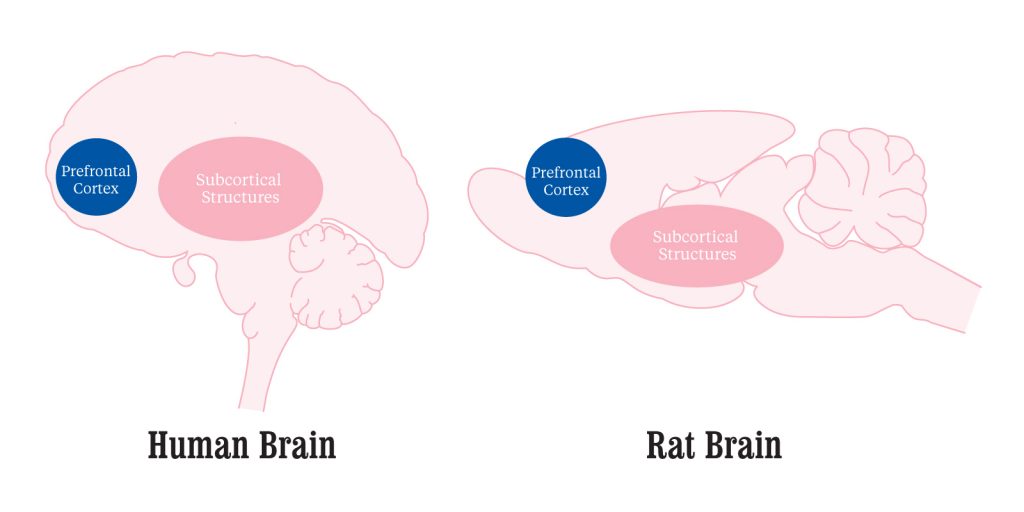

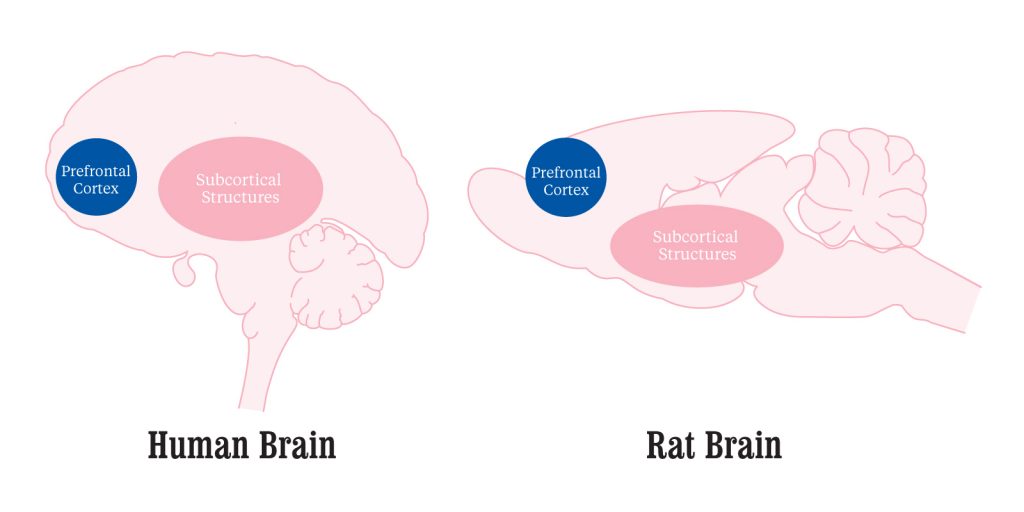

Both casual observation and systematic scientific research show that play is at its most frequent and exuberant in animals with the biggest brains. When comparing the brains of mammalian animals like us with other species, we see that the biggest size differences in brain size are in the anterior regions of the brain, the cortical hemispheres (figure 7). This is the large, greyish folded tissue that would be exposed if the top of your skull were removed. Animals with an enlarged cortex tend to be more playful. However, surprisingly, juvenile rats that have had their cortex removed at birth are just as playful as their siblings with an intact cortex. They play as frequently, perform all the same actions, have the same percentage of role reversals and show the typical age-related pattern of waxing and waning in the frequency with which they play. To understand this seeming paradox, we need to know some neural and behavioral details about play.

Decades of work from various laboratories have revealed the network of neural circuits that are necessary to generate play. Some of the circuits that are activated are necessary for making play enjoyable, some select the actions to be performed during play, and others still are necessary to ensure that play remains reciprocal. Importantly, all the necessary structures comprising these circuits lay beneath the cerebral cortices and hence are not visible from an outside view of the brain (as in figure 7). While play is generated and maintained by this network of subcortical structures (i.e., beneath the cortex), the cortex is not inactive during play. The nerve cells of various parts, especially the prefrontal cortex, are activated.

This area of the cortex is known as the “executive brain,” receiving information from the rest of the cortex and having many reciprocal connections, including to subcortical systems that are critical for planning and implementing actions and for regulating emotion. Rats reared without peers during their juvenile period (from weaning to the onset of sexual maturity) exhibit a range of social, emotional, and cognitive deficits that implicate changes in the functioning of the prefrontal cortex. A particularly noteworthy function of the prefrontal cortex is impulse control. In humans, an example of impulse control would be the ability to count to ten before responding to someone’s insult. Rats that have not had play experiences with peers as juveniles over- or underreact to threats and fail to plan or execute a strategy that solves a social problem. They can execute all the rat-typical behavior, but appear to be deficient in modifying the timing and vigor of the behavior that is executed. Indeed, damage to areas of the prefrontal cortex in adult rats produces deficiencies similar to those seen in rats with intact brains, but which have been deprived of peer play as juveniles.

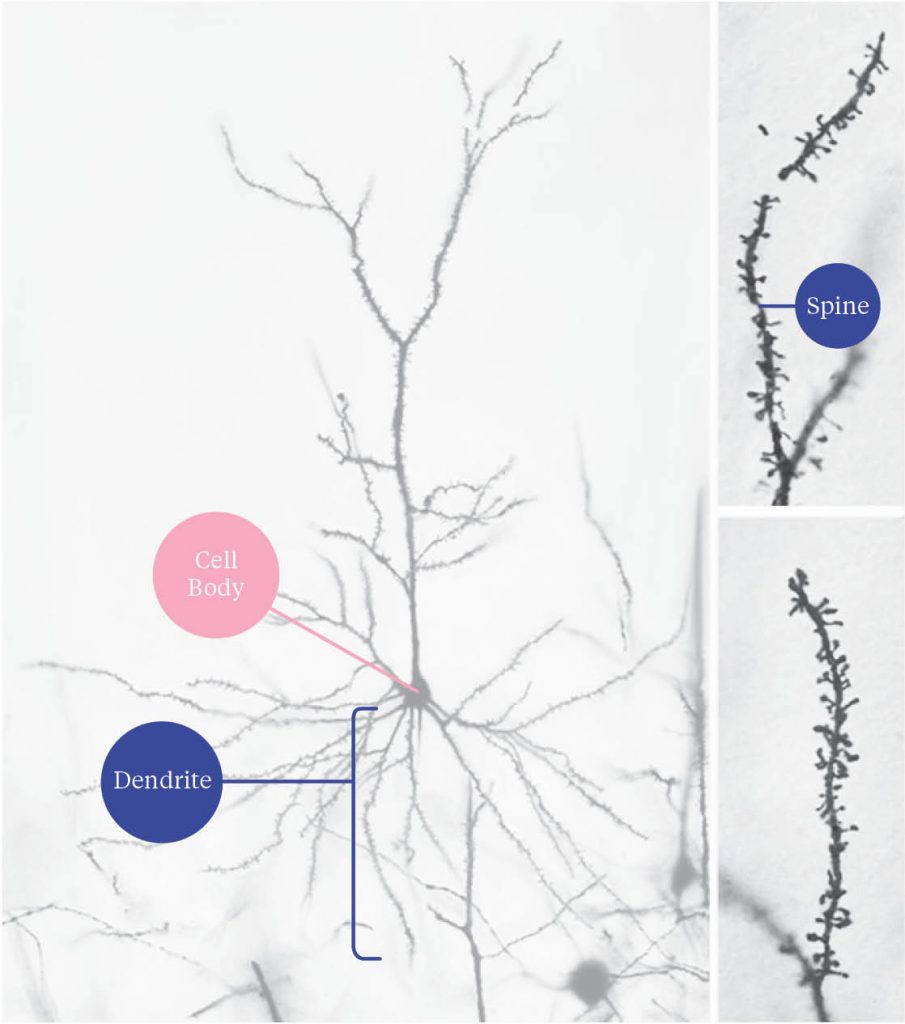

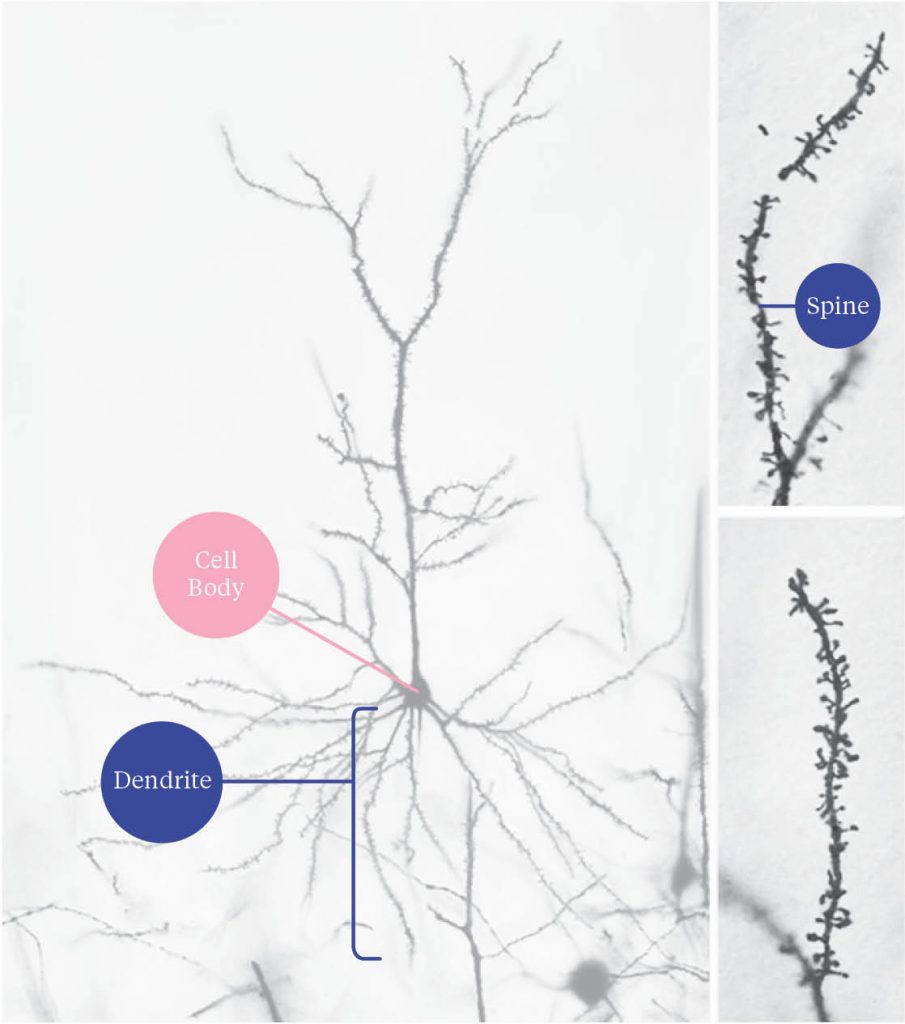

The photographs in figure 8 show what a neuron, a nerve cell, in the prefrontal cortex looks like. There is a central cell body, a long extension—called a dendrite—from which thin branches radiate, much like limbs on a tree. From those thin branches, smaller extensions known as spines receive chemical signals from other neurons. The complexity of the branching and the density of these spines allow neurons to form the many connecting networks that produce and regulate thoughts, feelings, and actions (figure 8). When damaged, the prefrontal cortex does not disable the animal’s ability to execute species-typical behavior; instead, the damage leads to a deficiency in contextually modifying that behavior to correspond with the identity and behavior of a partner.

The behavioral experiences provided by a normal peer compared to those provided by a relatively non-playful partner are revealing as to how these may influence the development of the prefrontal cortex. Rats reared over the juvenile period with a relatively non-playful partner have, as adults, deficiencies in such contextual modulation and atypical development of the anatomy of the prefrontal cortex. These changes in social experience affect the normal development of the neurons of the prefrontal cortex—altering the complexity of the neuronal structures involved in interneuronal communication. How do such changes come about?

The normal juvenile initiates more play with such a partner and has as many playful interactions as does a juvenile with a playful peer, but there is an important difference. With a non-playful partner, the juvenile experiences fewer opportunities to gain the advantage and then to relinquish that advantage by self-handicapping itself (as in figure 6), and so giving the partner an opportunity to reverse roles. That is, the juvenile engages in just as much play, but that play does not offer the opportunity to make social decisions about when to withhold its advantage. When a rat self-handicaps itself, it essentially relinquishes control over its own body, creating unpredictable conditions. Not overreacting to loss of control, coping with unpredictability and deciding on socially appropriate actions are all requirements on the performer when engaging in normal play fighting with a peer. The experiences generated call upon the skills associated with the prefrontal cortex, training this brain area to become more adaptable in an unpredictable world. So, although the cortex may not be necessary for generating play, the cortex, especially the prefrontal cortex, benefits from the experiences generated during play.4

Read on with the second half of Sergio Pellis’s piece on the uses of play for children and adults tomorrow.

1 Gordon M. Burghardt, The Genesis of Animal Play (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).

2 Sergio M. Pellis and Vivien C. Pellis,”Play-fighting differs from serious fighting in both target of attack and tactics of fighting in the laboratory rat Rattus norvegicus,” Aggressive Behavior 13 (1987): 227–242.

3 Afra Foroud and Sergio M. Pellis, “The development of ‘roughness’ in the play fighting of rats: A Laban Movement Analysis perspective,” Developmental Psychobiology 42 (2003): 35–43. See also Sergio Pellis and Vivien C. Pellis, The Playful Brain: Venturing to the Limits of Neuroscience (Oxford, UK: Oneworld Press, 2009), to place these actions in a broader comparative context.

4 For further reading, see Sergio M. Pellis, Vivien C. Pellis, and Brett T. Himmler, “How play makes for a more adaptable brain: A comparative and neural perspective,” American Journal of Play 7 (2014): 73–98; L. J. M. J. Vanderschuren and Viviana Trezza, “What the laboratory rat has taught us about social play behavior: Role in behavioral development and neural mechanisms,” Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience 16 (2014), 189–212.

(Image credits: Nick Cave performers at the Peabody Essex Museum. © PEM. Two Japanese monkeys playing, courtesy of Jean-Baptiste Leca, University of Lethbridge. Octopus engaged in object play, courtesy of Michael Kuba, Max Planck Institute for Brain Science, Frankfurt. A soft-shelled turtle and a Komodo dragon engaged in object play, courtesy of Gordon Burghardt, University of Tennessee. Drawings of two juvenile male rats engaged in a play fight, reproduced from Sergio Pellis and Vivien C. Pellis, “Play-fighting differs from serious fighting in both target of attack and tactics of fighting in the laboratory rat Rattus norvegicus,” Aggressive Behavior 13 (1987), courtesy of Wiley. Drawing of a rat standing on its partner with all four paws, redrawn from illustration in A. Foroud and Sergio Pellis, “The development of ‘roughness’ in the play fighting of rats: A Laban Movement Analysis perspective,” Developmental Psychobiology 42 (2003), with permission from Wiley. Dendrite images, courtesy of Bryan Kolb of the University of Lethbridge.)