Play has multiple benefits for children—and adults. But what is it about how we play that’s so beneficial? In part 2 of his essay, neuroscientist Sergio Pellis tells us: it’s the comfort of the familiar combined with the spirit of the unpredictable. Missed part 1? Check it out here.

Beyond childhood and the adult uses of play

While play is most commonly associated with childhood, some species, including rats, dogs, and more than fifty percent of all primate species, retain play into adulthood. Some of this play may be useful to relieve stress, maintain friendships, and ensure skills are kept well honed.5 The very qualities that make play fighting playful, and that in juveniles generate the experiences important for brain development, are also the qualities that make it a useful tool for social assessment and manipulation. When two adult playmates have an established social relationship, with one dominant over the other, the play fighting involves the same give and take routine already noted, but the inferior partner may reinforce that social status by altering the role reversal ratio in favor of its partner. Alternatively, the inferior partner may play more roughly than expected, not conceding the advantage to its partner. If the dominant partner tolerates such a situation, the inferior animal may push its luck further and so test whether it can reverse its status. A forceful put down by the dominant, conversely, signals that the dominant is retaining its superior position.

Similarly, when strangers meet, a playful interaction may be a way to assess one another without having to resort to serious aggression. For example, consider the use of jokes between colleagues when settling into a new job. Such jokes, as a form of play, can test the relationships and personalities of your potential colleagues and allow you to assess your position in the order of things. If a joke is too off color, or perceived as a put down, then you can back away with, “sorry, I was only joking.” Indeed, playful flirting is a common tactic for humans to break the ice in more romantic settings. In this case, a playful, gentle punch to a shoulder can be very informative as to whether such closeness is welcome or unwelcome – again, allowing either partner a graceful exit before a bigger faux pas is made.

In play, any given action can be ambiguous. Was that a deliberate transgression of the rules, or was it a mistake due to the excitement of the moment? Yet such ambiguity serves a purpose. Among juveniles, such ambiguity taxes the capabilities of their developing prefrontal cortex, helping them to hone their skills. With adults, such ambiguity creates plausible denial—“I didn’t mean to punch you so hard, I was just playing.” The nuanced skills needed for navigating such ambiguity in adulthood depends on the same prefrontal cortex mechanisms that are improved by juveniles via the experiences gained during play. Species with larger brains, and hence a larger prefrontal cortex, can create even more complex cycles of ambiguity.

Playing with play

A core feature of play fighting is that it involves following a species-typical sequence of competition, such as the attack and defense of the nape in rats (figure 5 in part 1). To a degree, the sequence has a predictable pattern. A rat perceiving its partner approaching will adopt a defensive tactic that blocks access to its nape, even if its partner has just contacted its rump, not its nape. The unpredictability arises from the partner in the advantageous position momentarily relinquishing that advantage. For some species, however, a different form of unpredictability can be introduced. In the close cousin of the chimpanzee, the bonobo, play fighting involves competing for access to the shoulder, which if contacted is gently bitten. Typically, two animals approach one another face-to-face then they grapple with their hands and weave in and out, lunging to bite each other’s shoulders while evading counter bites.

Such encounters have a stereotyped predictability about them, and yet they remain subject to unpredictability. On one occasion, I saw a young, juvenile female and an older, adolescent male playing in this way for many minutes, with repeated attacks, wrestles and withdrawals. Then, suddenly, the female came running toward the sitting male as she had done countless times before, but this time, did something different. As he raised his arms ready to grab her as she lunged at his shoulder, she rotated around fully as she jumped toward him, landing with her mouth contacting his groin and her feet grasping his head. He fell backward, chest heaving, mouth wide open, and making noises like human laughter. I suspect that he was as surprised as I was by this unexpected maneuver. She broke the species-typical play theme!

Such “theme breaking” must be even more demanding of the prefrontal cortex, both for the theme breaker and the ability of the partner to identify this correctly as play and not some aberrant action by a demented animal. Yet theme breaking is relatively common not only in bonobos, but also in chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans. It is less common, but present in some other species of primates, especially some monkeys, such as the New World spider monkey. What these species have in common is a particularly large brain, with a well-developed prefrontal cortex. A demanding social system that entails complex social relationships also challenges the development of the prefrontal cortex in a species. Being well endowed with a prefrontal cortex and confronting a demanding social system appears to generate the kinds of capacities in the prefrontal cortex that can create the ability to play with play that may be particularly valuable as a means of further sharpening those prefrontal cortex–derived abilities.

Humans have these two attributes—a very large prefrontal cortex and an exceptionally complex social system. As such, it may not be surprising that humans are highly playful and play in more diverse ways than any other species. We have taken the heritage we have in common with bonobos and developed it to unanticipated dimensions.6 Art may be the quintessential expression of such playfulness. After all, much art repeats well-known themes, but artists can insert unexpected twists and turns into those themes. This unites the comfort of the familiar with the frisant of the unpredictable, tapping into the roots of what we find pleasurable in play: it is a way in which to explore the unknown while remaining anchored in the known. ♦

5 For further reading, see Charmalie A. D. Nahallage, Jean-Baptiste Leca, and Michael A. Huffman, “Stone handling, an object play behaviour in macaques: Welfare and neurological health implications of a bio-culturally driven tradition,” Behaviour 153 (2016), 845–869; Elisabetta Palagi, “Playing at every age: Modalities and potential functions in non-human primates,” in Anthony D. Pellegrini (ed.), Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011), 70–82.

6 For further reading, see Angeline S. Lillard, “Why do the children (pretend) play?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21 (2016), 826–834; Sergio M. Pellis and Vivien C. Pellis, “Play and cognition: The final frontier,” in Mary C. Olmstead (ed.), Animal Cognition: Principles, Evolution, and Development (Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, 2016), 201–230.

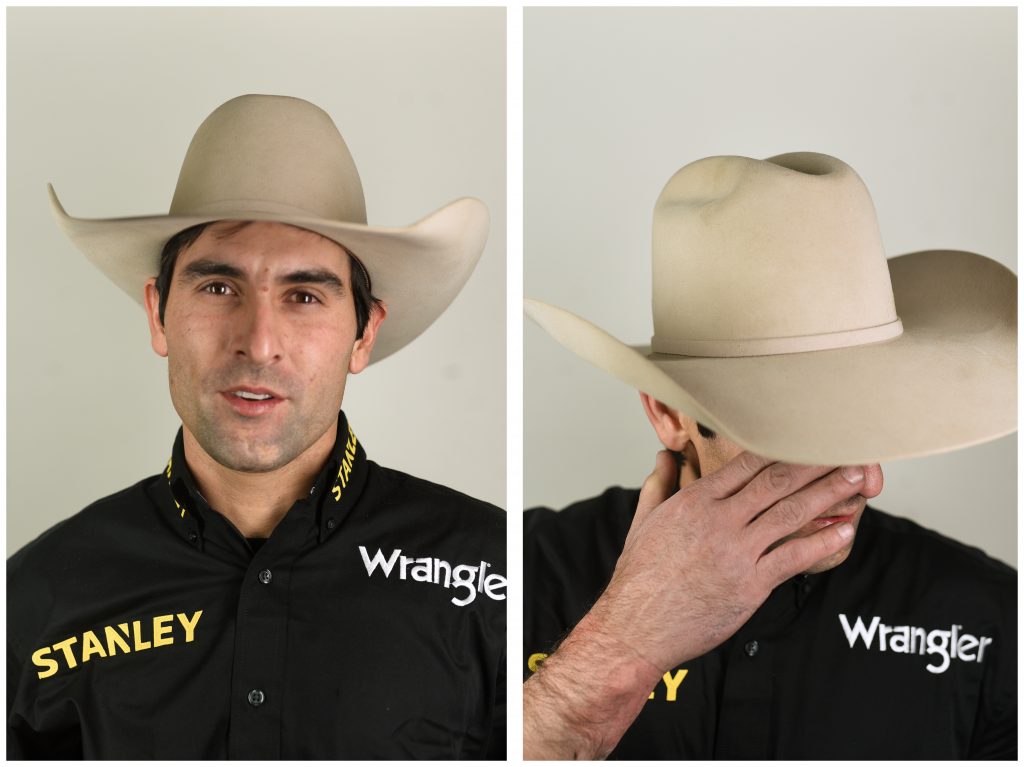

(Image credit: Nick Cave performers at the Peabody Essex Museum. © PEM.)