Roleplaying games, long defined by the likes of Dungeons & Dragons, have expanded—as game designer and writer Adam Dixon discusses here—to include broad new descriptions of the culture-impacting characters we assume playing them.

This is our ritual: every Monday we sit around this table, covered with paper and pencils, books, and dice. Six of us. We talk, share jokes, and catch up until the sky behind the window turns black. Then we begin, we take on our roles. Five of us become someone else, we become actors playing a character we’ve designed. The other leads us in the ritual. They knit together a fictional world and all the people within it.

Games create stories. In between their structures and rules are gaps we fill with our own narrative—a fruitful void. This void is everywhere a game isn’t, the places where art, world building, writing, and mechanics don’t touch. It’s an invitation for players to create, to be playful with story. For some games this is a happy accident, an aside—when we play Cluedo we might create personalities for Mrs. Plum and Colonel Mustard. It adds to our enjoyment of the game, but isn’t really intended. Other games use the void purposefully: The Sims gives us tools to build characters, a house, a world, and then asks us to infer our own narratives and motives from the abstract language and actions on screen.

Words are our most important currency.

A man, covered head-to-toe with strange tattoos, appears as if from nowhere under the streetlight. “Help me,” he says, grasping your wrists, “They’re coming.” What do you do?

You’d never paid much attention to Darius before. You’d always thought he was leagues above you, it could never happen. But it is happening. He is walking towards you, frost-fire eyes locked on yours. What do you do?

For days your head has been under bombardment—pain, hallucinations, fever. You’ve spent half of your week locked in your darkened bedroom, but they still won’t go away. Tonight, your friend who is normally half the world away, is in town. What do you do?

This is about games that tell stories on purpose, that use mechanics to create spaces for players to tell stories—roleplaying games. Games played as a group, usually in real life though sometimes through Skype or Hangouts. We collectively imagine a world and tell a story that happens within it. We play with paper and dice, though words are our most important currency.

Dungeons & Dragons is the most famous of these games. A fantasy game where we play as elvish paladins, half-orc mages, and halfling rogues, raiding dungeons to protect the world and steal treasure. It’s the roleplaying game that normally appears on television shows, it’s the one that most people play first, it’s the one other games rally against. Let’s get out from under its shadow.

Roleplaying games aren’t all Dungeons & Dragons. There are games of countless genres, that explore mature themes, that have simpler rules, that are radical in rules and content.

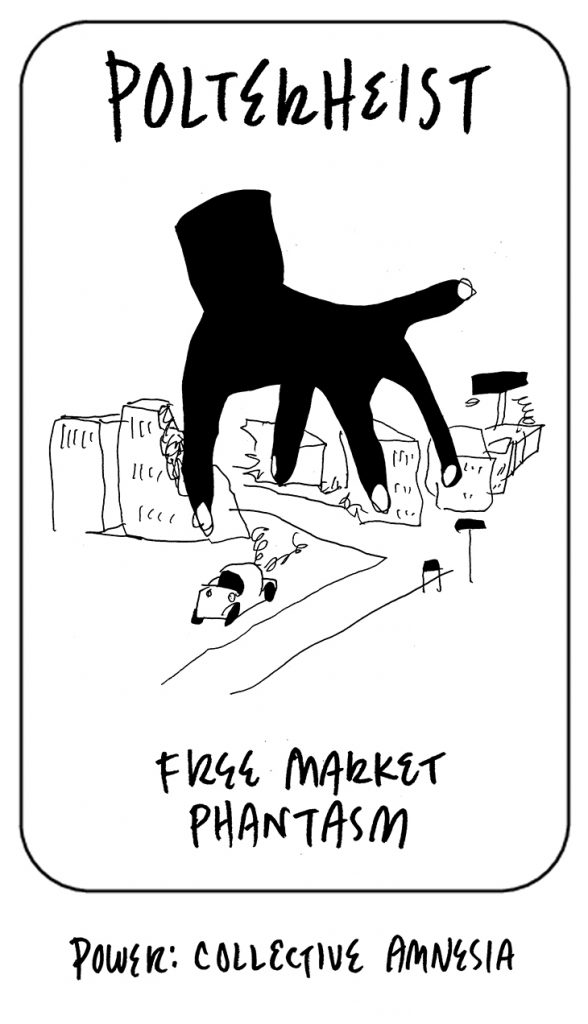

Storygames, or indie roleplaying games, began as a movement in the early 2000s, defined by both their independent development, and, more importantly, their narrativist design. At the heart of storygames is the desire to put story first, the mechanics work to drive the narrative forward. Storygames tend to focus on a particular kind of story, and give players the tools to best tell it. We might tell a story of people trapped in a love triangle, play out a Coen brothers heist where everyone is down on their luck, or remember a made up arthouse film.

Limits of character

Usually the first step of playing a storygame is to create characters. We spend time together designing the person we want to play. We assemble a rough collection of stats, abilities, and traits that go some way to define who we’re playing. We give everyone an idea of who we want to be and then we play to find out more about them. We use these fragments to create a rounded person.

We often play people who are different from us; we might be a different species or have abilities that we don’t posess in real life. This creates space for transgressive play. We can occupy characters that have different genders, social classes, or sexualities than us; we can use our characters to explore ourselves, our fantasies, and the issues we care about.

There are games that go out of their way to encourage this style of play. Apocalypse World creates an environment that explicitly undermines the masculine, capitalistic power fantasies seen in a lot of post-apocalyptic fiction. In its character creation it foregrounds different expressions of gender. We make a choice of both our gender—ambiguous, female, male, transgressing—and how we express it, through a choice of the fashion we wear.

Role-playing can be a space for transgressive play.

Apocalypse World has inspired a range of games. Using similar rules and mechanics, there are Powered by the Apocalypse games of every genre, from steampunk to comedy. Many of these games also adopt Apocalypse World’s progressive politics. Night Witches explores the realities of being a woman pilot in the Soviet air force, players dogfight the Nazis at night and face their own femininity—and people’s reactions to it—by day.

In Monsterhearts, we play teenagers in a high school where feelings of adolescent monstrousness are made literal. Our characters aren’t just students, they’re also werewolves, ghosts, witches, and ghouls. Figuring who we are and where we belong in the world is a central theme of the game, and our character’s sexuality is a large part of this. The rules explicitly tell us not to define our character’s sexuality, we must play in order to discover it. When someone tries to turn on our character, we use the dice to see if it works, to see what we find hot. How we react to that, how our character feels about what turns her on, is entirely down to us.

It is through our characters that we are given permission to explore our expressions and our fantasies, and whatever we choose, the implications of character bleed through into our game. ♦

In part 2, Adam Dixon looks at the growing impact of community, immersion, and empathy in role-playing games.

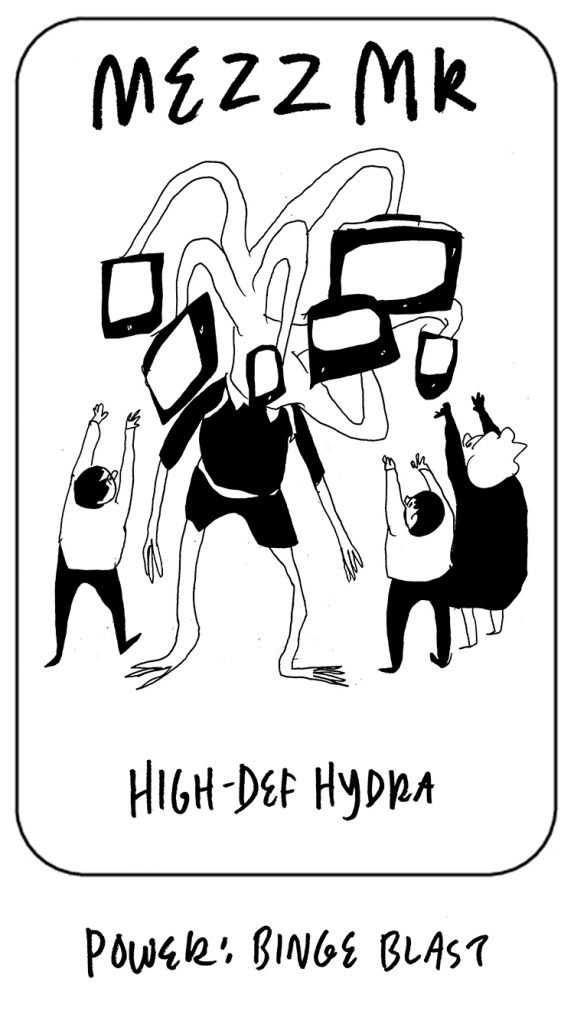

(Image credit: Feature image by and courtesy of the author. Apocalypse World image courtesy of D. Vincent Baker and Meguey Baker.)