“Play is movement within constraints.”

—Tracy Fullerton, director of the Game Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California

“Play is movement within constraints.”

—Tracy Fullerton, director of the Game Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California

We’ve met extraordinary artists, scholars, and fans of play while out and about in the field. We asked them to complete our manifesto and tell us “Play is . . . .” Here are their responses.

Featured in this video are Pedro Reyes, Eric Zimmerman, Jade Ivy, Eric Turiel, Tritemare, Charlotte Richards, Mattie Brice, Travis Larchuk, Jaden D. Francis, Tracy Fullerton, Jane Friedhoff, Sam Roberts, Alioune N’gom, Everett Phillips, Duke DeVilling, Kristen Skillman, Randall Roberts, Amanda Penny, Courtney Price, and Stephanie Barish.

Read the transcript.

(Music by Green North by DKSTR [CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US].)

Horner tells us more: “Times are changing. As technology continues to press into the social realm, the shape of our tools outlines how we create, identify, and PLAY. With quick access to camera and video technology, people around the world are sculpting themselves in ways previously unknown to the darkroom. The makeup industry is booming, and apps used to both define and contort are becoming a fixture of internet culture and self expression. Real-life communication and video game fantasy grow closer each day; in a way, we are each creating our own AVATAR . . . which player are you?”

Here, in the museum: a spectacle! To the melody of “Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity” from The Planets by composer Gustav Holst.

Look for a new installment from Juliana Horner next month.

“Play is a trust exercise. Close your eyes and fall backwards and hope that they catch you.”

—Sam Roberts, Festival Director, IndieCade

Music—loud, insistent, and dissonant—makes remaining calm difficult. Clanging bells, penny whistles, and what is probably a toy piano ride treble-high over a honking bass saxophone playing “Yakety Sax” at half-speed. It’s a funeral march for a suicidal clown, or that’s what Sandy surmises. She observes Bean at the kitchen table fiddling with his laptop, jumping from one noisy video to another and judges the probable success of hitting him from across the hall with the mug she squeezes with increased annoyance. Just thump him in the back. Divert his attention from playing whatever he’s playing. As this only slightly violent thought discharges its modest current, she’s conscious of the weight and hardness of the mug. An empathy too finely tuned allows her to absorb the sensation of being hit with it and there, in the big armchair, she flinches.

“Bean, please,” Sandy says. To herself, though. Louder then, “Bean, please turn it down.”

“Yeah, turn that shit off,” Jack shouts as he descends the stairs. He holds his hands out, palms up. “Who took the towel out of the bathroom?” “We need it for Blind Man’s,” Bean declares as he brandishes the purloined hand towel and calls the group to form a circle.

People from Jack’s office are here; some college friends of Jess’s, too. No matter the increased numbers, he chooses Sandy—she knew he would as if in retribution for those angry thoughts—and soon her face from forehead to the tip of her nose is draped in a towel held in place with a binder clip that catches a hunk of her hair.

“Hey,” she says. The towel smells like sink.

She sits in the big chair while they dance around her—yes, dance; it’s not a pretty sight—until she gives a signal. She could clap, or shout “Stop.” When everyone halts Sandy will point to one of the players and that person will have to make a vocal sound that’s been determined in advance. They may have to imitate the sound of an animal named by the blind man, sing a song, speak in tongues, or impersonate Lucille Ball discovering a bat in her bedroom. Tonight, Sandy asked that those she selects cry like an eight-year-old who has been sent to their room for backtalk. She has one shot at identifying the player; if she succeeds, the two trade places. If she fails, she will continue drawing breath through what increasingly stinks of drainpipe.

The circular cavorting begins; the floor’s vibrations make their way through the chair to Sandy. It’s a pleasant sensation, like she’s in a drink being stirred. She can’t see anyone and they can’t quite see her but she is at the center of things. She tightens a bit and calls out “Stop,” and the vibration recedes. People laugh. Someone trips, it seems, into someone else and there’s more laughing. Sandy stands, slowly turns, and with a regal flourish points into the darkness. She’s pointing out there, out past the circle, to the living room. Out there.

It’s a friend of Jess’s, the woman with chipped fingernail polish who has been popping out all evening to smoke on the stoop. She begins with tiny moans, more sexual than sad, but then pushes them higher, allowing a raggedness to creep in around their edges. It’s throaty and wet and everyone is quiet. They build quickly. Soon there’s something undeniably genuine; the choking catch begins to spark some small alarm. She is wailing and heads turn away or down because there is fear that this woman’s face will be streaked with tears. And then, as if a needle jumped its groove, the sound ceases and is replaced by her panting— healthy exerciser’s panting—as if she’d done a steep stretch on the elliptical trainer. Slack faced, smiling, she covers her mouth to cough. The room temperature drops a few degrees as the flush of embarrassment ebbs.

Sandy knows that crying; she hears all of its parts and pieces. In the dark, she can see it. Jagged streaks of chalk across a blackboard crisscrossing and swirling over and over until the blackness is almost hidden behind a veil of white dust and grit. And when it stops, she knows who is crying, too—the cough is the clue. She thinks about the fingernail polish, chewed away or just neglected. You would have to disown that cry wouldn’t you? Sandy is about to say her name but doesn’t. There’s someone else here who could cry like that. There’s someone whose name she says out loud with a little glee, with a little accusation.

Photo credit: Detail of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Blind Man’s Bluff, oil on canvas, 1755–56, Toledo Museum of Art, from Wikicommons.

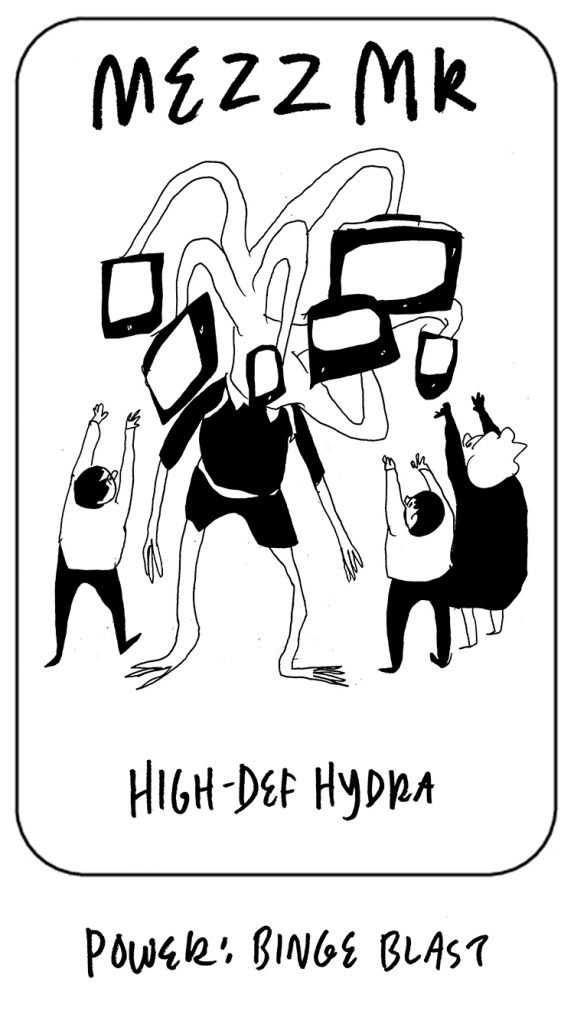

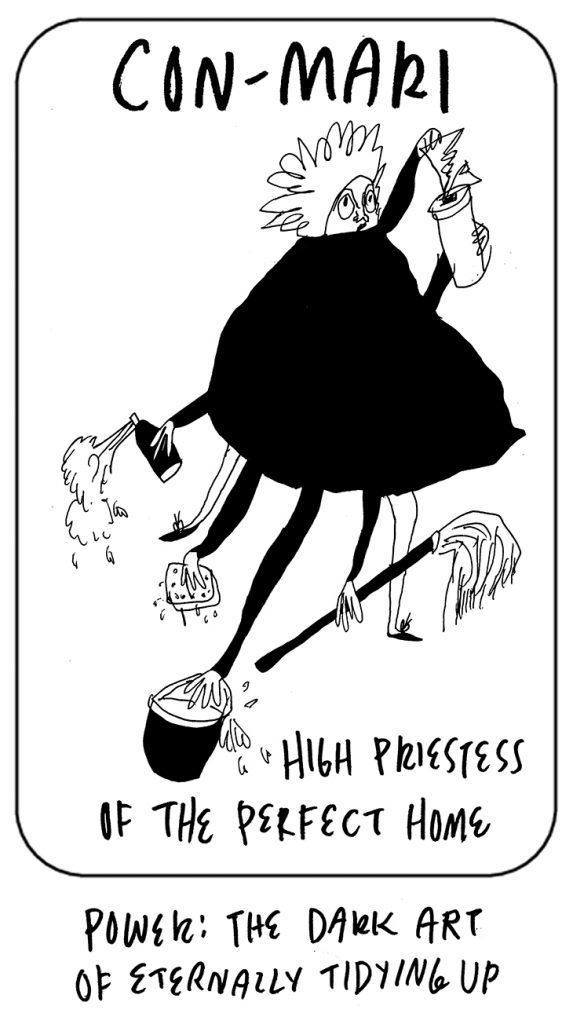

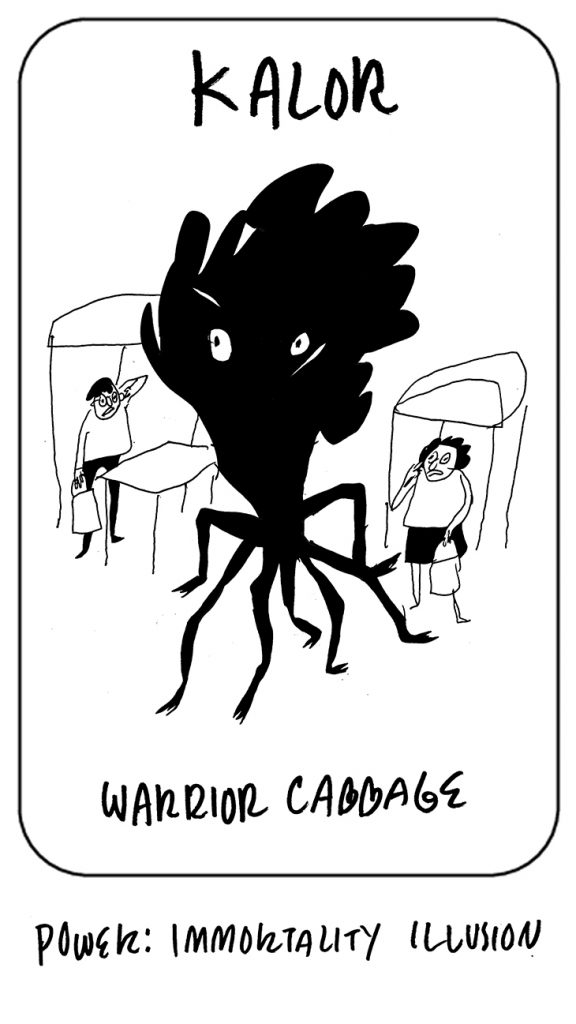

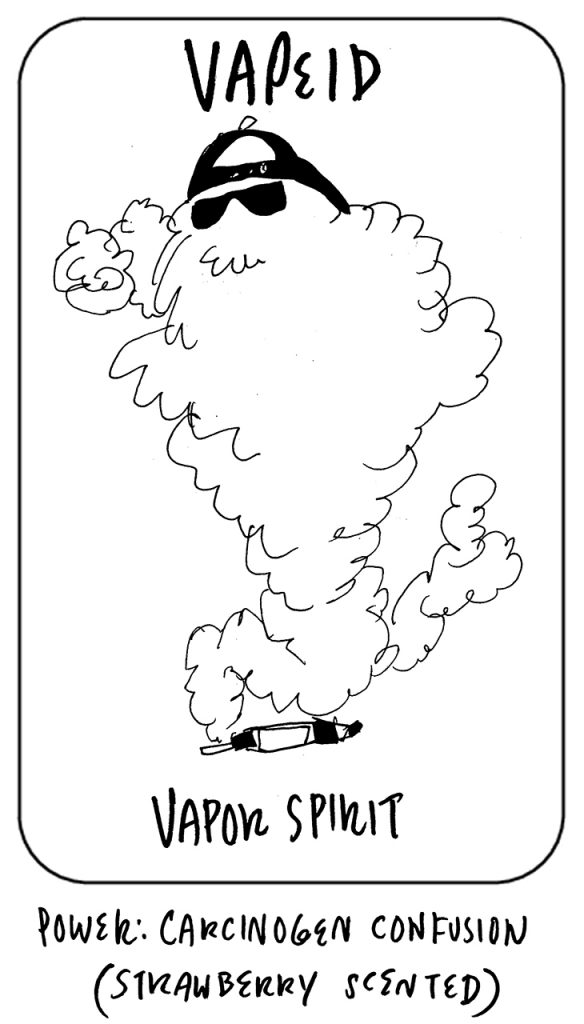

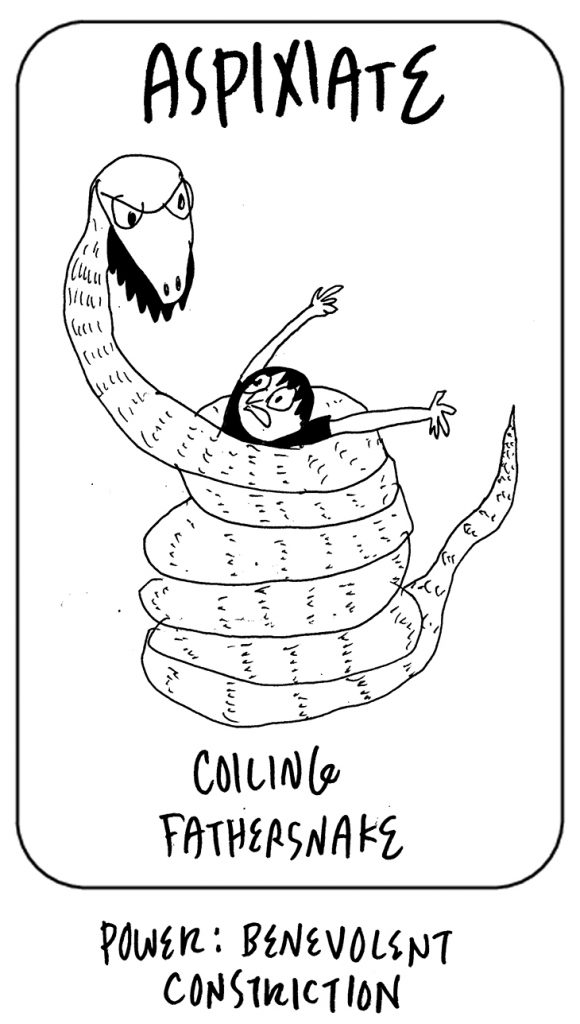

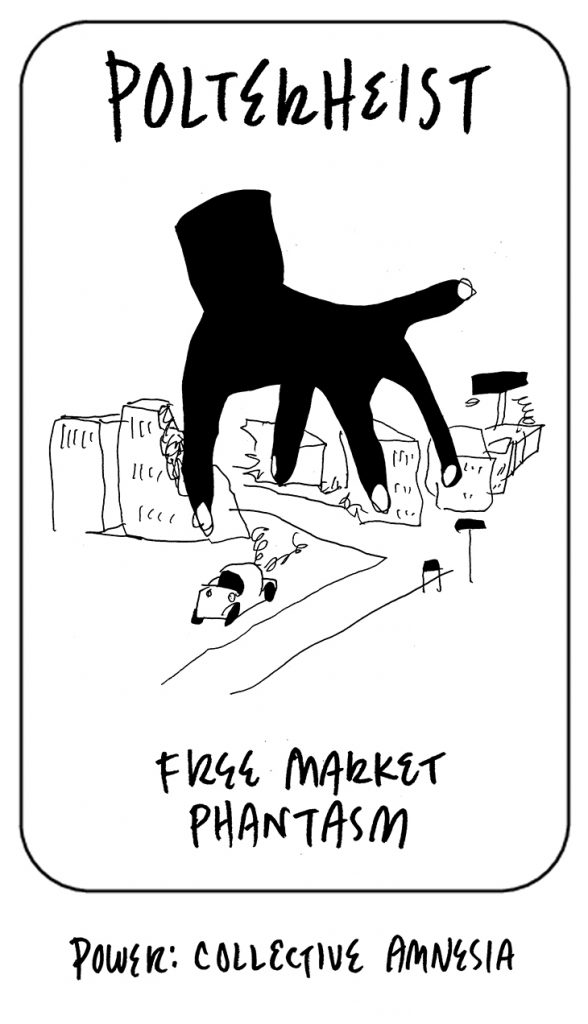

Before Pokemon gave us “Catch’em All,” there was Magic: The Gathering, a card game invented in the early ’90s that burned through teenage allowances faster than dragon fire. If you’ve never played Magic, you’ve certainly seen the fantasy roleplaying game at your local coffee shop, an entire table filled with animated characters—and that’s just the players, whooping and hollering after a ghost warlock decimates an upstart ice golem with a flaming spellblast. In 2017, what new magical creatures might we add to our deck?

Come back for next month’s installment in the Board Gaming the System comic series. Missed the last one? Check it out here.

The idea for the adventure playground originated in postwar Europe and was championed by the English landscape designer Lady Marjory Allen, who vocally advocated for children and their right to play. New York’s latest adventure playground, on the Governors’ Island, celebrates tinkering and “playwork,” a concept pioneered in what was known in the early years of the adventure playground movement in Denmark as “junk playgrounds.” Adventure playgrounds are many things: precincts of invention (of the self and of playscapes), environments for imaginations to run gleefully amok, and, significantly, an education in managing risk, as highlighted in the documentary called The Land, about the Welsh adventure playground of the same name.

The Land (Teaser) from Play Free Movie on Vimeo.

Adults aren’t typically allowed to even enter adventure playgrounds (unless they are one of the employee facilitators). In Berkeley, California, which has a well-known, nearly forty-year-old adventure playground on its waterfront,the coordinators observe that many parents don’t know how to play.

Some playgrounds spring from the imagination of the designer or architect with the full intention of freedom (Julia Jacquette’s graphic memoir will explore this a little, her father was an architect who designed a well-loved playground in Central Park), but many playgrounds fall victim to architectural “control.”

Last year’s Extraordinary Playscapes exhibit at the Boston Society of Architects looked at how playspaces impacted young minds and examined some of the best international examples of playground design.

The anonymous play sculptures of our childhoods (designed by Jim Miller-Melburg) get a show of their own in Detroit.

Accessibility and inclusivity should be not just social expectations of the playground experience, but physical ones too. Designing or finding accessible playgrounds shouldn’t be a chore—or even a question—for families with special needs.

Niki de Saint Phalle’s Golem slide in Jerusalem was ahead of its time and now dearly loved, but there are plenty of other artist-designed (deliberate or not!) playgrounds around.

Check in next week for a new roundup of the latest play news and stories.

(Photo credit: Image of the Monster Slide, Kiryat HaYovel, Jerusalem by Brian Negan on Flickr.)

“Play is your inner child reminding you not to take life so seriously. It allows you to explore the world in a way that’s free of limitations and fear.”

—Claudia Eliaza, musician, music therapist, and storyteller

“Play for me is always about using my hands and some sort of material, then letting my brain wonder and instinctively combine the two. It’s not about an outcome, it’s about the process of not having to think about an outcome.”

—Donna Wilson, designer

As fathers of young children, Jason and Adam have spent many fun hours playing board games, several of which were created by Parker Brothers, which made its start as a game company right in Salem, Massachusetts. These board games aren’t just about diverting play, but about rules you must follow to win. The rules of game often reflect the idealized rules and mores of the culture—by playing the game, you are learning how to behave in the culture. And thus, board games are like a time capsule, a way of seeing the dominant values of a place and time. Our five-part series, Board Gaming the System, honors the legacy of the board game (and the many hours we’ve spent playing them) and reimagines classic boards to reveal the unwritten rules of our culture today.

Come back for next month’s installment in the series.

Across

1. What some jeans do

4. Winter pear variety

8. Got along

13. “That’s so not cool!”

14. Sea creature that can swim 40 mph

15. Top 10 hit for Elvis Presley and Lil Wayne

16. S

E

R

18. Add lots and lots of

19. “Hell ___ no fury . . . ”

20. Kind of board used for spelling

22. Catch red-handed

23. “The Lord of the Rings” actor Sean

25. Ope[rat]ion

28. You might skip them

30. Carrier to Sweden

31. Letters on a stick, in cartoons

32. Nintendo game with a Balance Board

35. Bara of silent films

37. Sergio

40. Chicken serving

41. ___ meteor shower

42. Glass on the radio

43. Quarterback Manning

45. Like a small garage

49. TLARH

53. Chosen one in a kids’ game

54. Kung ___ chicken

55. Did some data entry

57. “Call of Duty: Black Ops” guns

58. Pitch perfect?

60. Peabody Essex Museum exhibition that suggests games . . . and an inspiration for this puzzle

62. Colorful aquarium fish

63. 2016 Isabelle Huppert film

64. Really long time

65. / or \

66. Female deer

67. Movie format, eventually

Down

1. “For example?”

2. Open-mouthed

3. Needy part of a city

4. ___ choy

5. Cookies and Cream cookie

6. Rugby formation

7. Timex competitor

8. Batman, to the Joker

9. French for before

10. Banter

11. My Chemical Romance and others

12. Place to do a jigsaw puzzle

15. Capital of Tibet

17. Friendly conversation

21. Angry partner’s dismissal

24. Disagreeable choice

26. Leftmost member of a violin quartet?

27. ___ meeting

29. Basic dog command

33. Adjective for a Persian

34. Wrath

36. Cops may search for one

37. Shell fragments

38. Italian bread inspired by the baguette

39. Palindromic singer

40. Shop ___ you drop

44. Facebook group?

46. Snuggled (up)

47. Author who coined the term “robotics”

48. Forward, perhaps

50. Personal letter sign-off

51. Did some data entry

52. Word on a name tag

56. Broad valley

58. They’re in the singular

59. “Meh, I’ll pass”

61. “Sure, I’ll do it!”