Foosball, Babyfoot, table soccer: whatever you grew up calling it, it is as culture-crossing and universal as the game on the pitch. Writer Tom Vanderbilt takes us to the table.

Whenever I walk into some space vaguely associated with recreation—a sleepy bar, a bowling alley, the grease-scented shack at the community pool—my eyes, without active thought, always flick to the corners. What I am hoping to see, and so rarely do, is some surviving example of that vestigial class of indoor table games: a Brunswick air hockey table, ready for its air jets to hum into quiet life; a Williams “Master Strike” bowling game, with a jar of that curious granulated wax to smooth the travel of the chrome puck; or, perhaps most eagerly, a foosball table (bonus points if all its players are correctly aligned on the rods).

This impulse was no doubt ingrained in me by time spent at a Midwestern university, with its combination of copious spare time and long, punishing winters. I certainly lost many hours to video games, but these were typically frantic, solitary bouts in between classes—the shaky fix of an addict. What really enchanted me were these analog pursuits, these little curious representations of real-world sports (soccer, tennis, hockey, etc.), rescaled for indoor consumption and bearing only a symbolic connection to their parents (a good soccer player would not necessarily make a good foosball player, and vice versa).

I sometimes have the idea that things are just another way to forge social connections by other means.

What was ultimately so appealing about these games—and from here I will focus on foosball—was not the gameplay itself, but the fact that they were social (you can hardly play foosball by yourself). The object itself had a magnetic appeal, like a watering hole in the Kalahari. It was inviting a ritual (chess, so often deployed as a decorative element in hotel lobbies and other places, does this too, although I rarely see anyone actually playing). Unlike video games, a number of people could play at once, four was better than two, forging a spontaneous social bond that was absent in the autonomous individual turn-taking of, say, Pac-Man—and a game might even attract spectators. It was Pac-Man and its ilk, actually, that were attributed to ending what had been something of a wave of foosball mania in the U.S. and elsewhere in the 1970s. There were professional tours, coverage in Sports Illustrated, ads for tables in national magazines. The pro tour continues, and tends to be dominated by a white-gloved Belgian named Frédéric Collignon, but it has never regained such dizzying heights (though there is a movement afoot to have it installed in the Olympics).

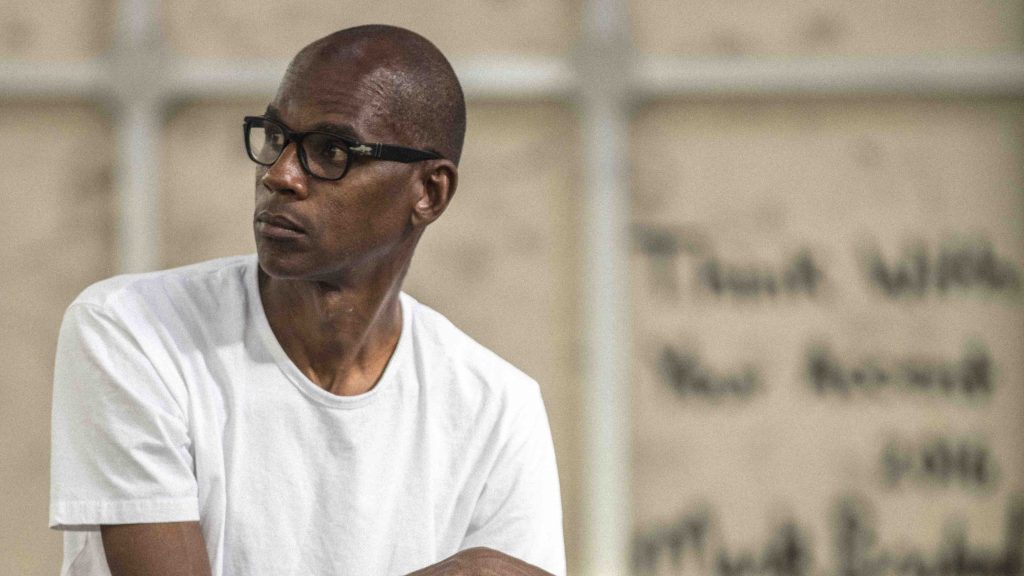

I sometimes have the idea that things are just another way to forge social connections by other means—that people go to events like collectible car shows primarily to talk to other people (about collectible cars). Here is where a foosball table, as a thing, has a power beyond itself. Take, for instance, a story that appeared in 2015 in the Boston Globe. It described one Cedric Douglas, an artist-in-residence at a group in the Boston suburb of Dorchester. After purchasing a foosball table for $50 off Craigslist, he began toting it around town, inviting strangers to play. He calls it “playmaking”—using the game to connect random people (who otherwise would not connect) to each other in the shared space of the neighborhood, around a kind of symbolic hearth.

The British artist Oliver Clegg had a similar impulse when he hosted a “Triathalon” at the offices of Cabinet magazine in Gowanus, Brooklyn. One of the featured contests was foosball (there was chess too, on a board designed by Clegg), conducted on a working table that was also a sculpture by Clegg, titled Self portrait with my wife (as foosball players), featuring hand-sculpted resin players that were, you guessed it, reproductions of Clegg and his wife, sans clothes (this personification brings to mind a news dispatch, from CNN, noting that the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria allowed the playing of foosball—so long as the faces or heads were removed “to prevent idol worship”).

We do not argue much over whether art can be a game.

The table was the art, but so was the play. This seemed meaningful. Enter the search terms “artist” and “game” and “play” into Google and you will get pages and pages of articles debating whether or not video games “are art.” We do not argue much over whether art can be a game. There was a quaintness in Clegg’s materiality, including his insistence that the foosball figures not be made using 3D modeling (so they had traces of real imperfection), as well as the idea of people interacting in real life over these human foosball figures. “Needing two hands to play a game of foosball meant you couldn’t post on Instagram,” Clegg noted in one interview, “and playing chess meant that your focus was more on winning than checking Facebook.”

It was not the first time foosball had been trotted out in the service of art. With his 1991 work Stadium, Maurizio Cattelan famously crafted an enormous foosball table—over nineteen feet long—to accommodate eleven players on each side (to mimic a real soccer match). At a time of increasing xenophobia, he paired a team of North African migrants against an “Italian” team; as the work’s Sotheby’s catalog entry describes, “the maneuvering of miniature color-coded figurines across a tabletop came to invoke a much larger metaphor for the greater theatre of world politics.” But like the other foosball-art interactions, what animated the work was the play. Without its human participants, Cattelan’s sculpture was mute; a symphony in a vacuum.

The foosball table can signify the sense of unstructured, campus-like fun of Silicon Valley culture or precisely as a symptom of the structural flaws of that culture.

If the iconic power of the foosball table helped provide a powerful medium for Cattelan’s socio-political expression, the foosball table has itself become symbolic. Anyone who had followed accounts of office life in Silicon Valley over the past decade or so will have noticed the inevitable appearance of the foosball table. The table became a kind of stock image. Literally—enter “foosball” into a site like iStock and you’ll get executives or hip-looking coders on break huddled around a table. Depending on the context, the table either seemed to signify the sense of unstructured, campus-like fun of Silicon Valley startup culture (where it became an amenity as standard as free snacks), or precisely as a symptom of the structural flaws of that culture (i.e., throwing employees a foosball table instead of good health insurance, etc.); “Is Anyone Really Using the Office Foosball Table?” as one article darkly put it. The foosball table rests uneasily in the office, violating an implicit boundary between work and play, raising suspicions that not enough work is being done or, perversely, that it’s gleeful team-building bonhomie masks a sinister campaign to get people to work harder and longer. But relax, it’s only a game. ♦

(Image credit: Courtesy Nicola via Flickr.)