Cory Arcangel

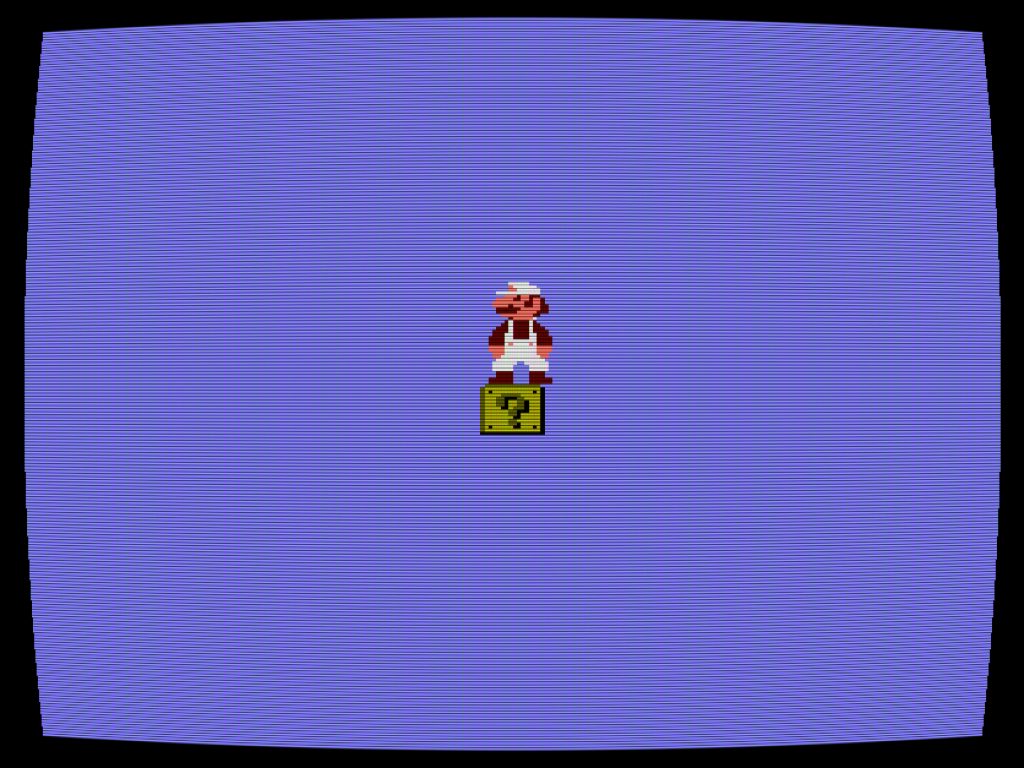

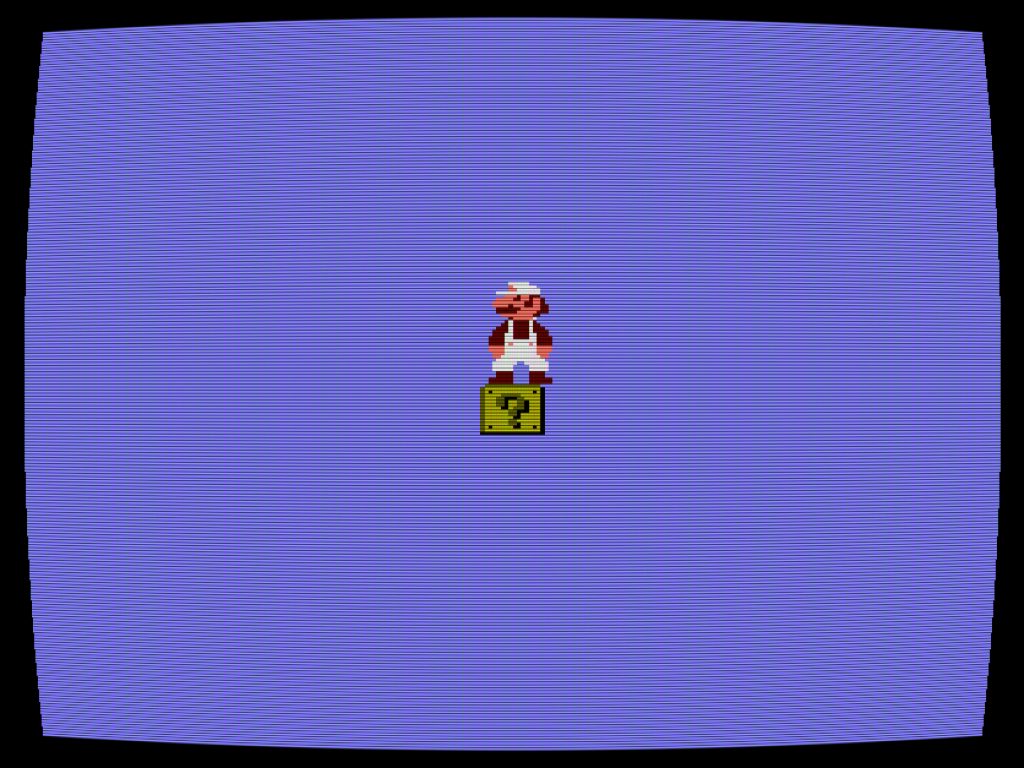

Cory Arcangel, still from Totally Fucked, 2003, hacked Super Mario Brothers cartridge and Nintendo NES video game system. On loan from the artist. Photo by Maria Zanchi. © Cory Arcangel

Cory Arcangel, still from Self Playing Nintendo 64 NBA Courtside 2, 2011, hacked Nintendo 64 video game controller, Nintendo 64 game console, NBA Courtside 2 game cartridge, and video. On loan from the artist. Photo by Maria Zanchi. © Cory Arcangel

Learn more about Cory Arcangel.

Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford, Practice, 2003, video (3 minutes). Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland.

Learn more about Mark Bradford.

Nick Cave

Nick Cave, clip from Bunny Boy, 2012, video (14 minutes). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Nick Cave

Learn more about Nick Cave.

Martin Creed

Martin Creed, Work No. 329, 2004, balloons. On loan from Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Martin Creed, Work No. 798, emulsion on wall, 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Learn more about Martin Creed.

Lara Favaretto

Lara Favaretto, Coppie Semplici / Simple Couples, 2009, seven pairs of car wash brushes, iron slabs, motors, electrical boxes, and wires. On loan from Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Learn more about Lara Favaretto.

Cao Fei

Cao Fei, Rumba 01 & 02, 2016, cleaning robots and pedestals. Photo courtesy of the artist and Vitamin Creative Space. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Cao Fei, still from Shadow Life, 2011, video (10 minutes). On loan from the artist and Vitamin Creative Space. Courtesy of the artist and Vitamin Creative Space.

Learn more about Cao Fei.

Brian Jungen

Brian Jungen, Owl Drugs, 2016, Nike Air Jordans and brass. On loan from the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York. Photo by Jean Vong.

Brian Jungen, Horse Mask (Mike), 2016, Nike Air Jordans. On loan from the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York. Photo by Jean Vong.

Brian Jungen, Blanket no. 3, 2008, professional sports jerseys. On loan from the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York. Photo by Jean Vong.

Learn more about Brian Jungen.

Teppei Kaneuji

Teppei Kaneuji, Teenage Fan Club (#66–#72), 2015, plastic figures and hot glue. On loan from the artist and Jane Lombard Gallery, New York. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Teppei Kaneuji, White Discharge (Built-up Objects #40), 2015, wood, plastic, steel, and resin. On loan from the artist and Jane Lombard Gallery, New York. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Learn more about Brian Jungen.

Paul McCarthy

Paul McCarthy, Pinocchio Pipenose Householddilemma, 1994, video (44 minutes). On loan from the Marieluise Hessel Collection, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. © Paul McCarthy

Learn more about Paul McCarthy.

Rivane Neuenschwander

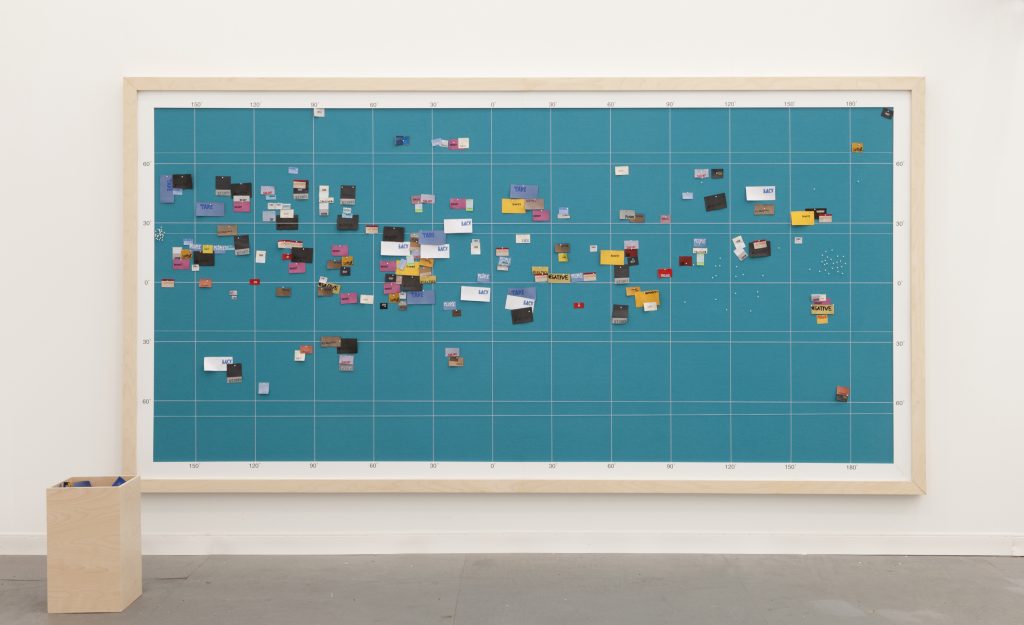

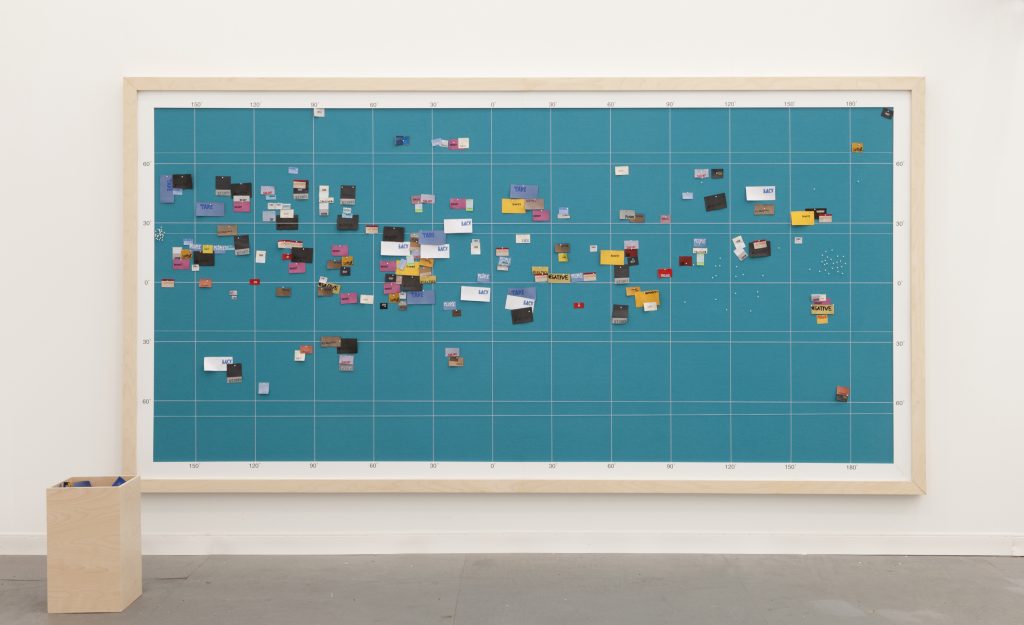

Rivane Neuenschwander, Watchword, 2013, embroidered fabric labels, felt panel, wooden box, and pins. On loan from the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, São Paulo, Brazil; and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London.

Learn more about Rivane Neuenschwander.

Pedro Reyes

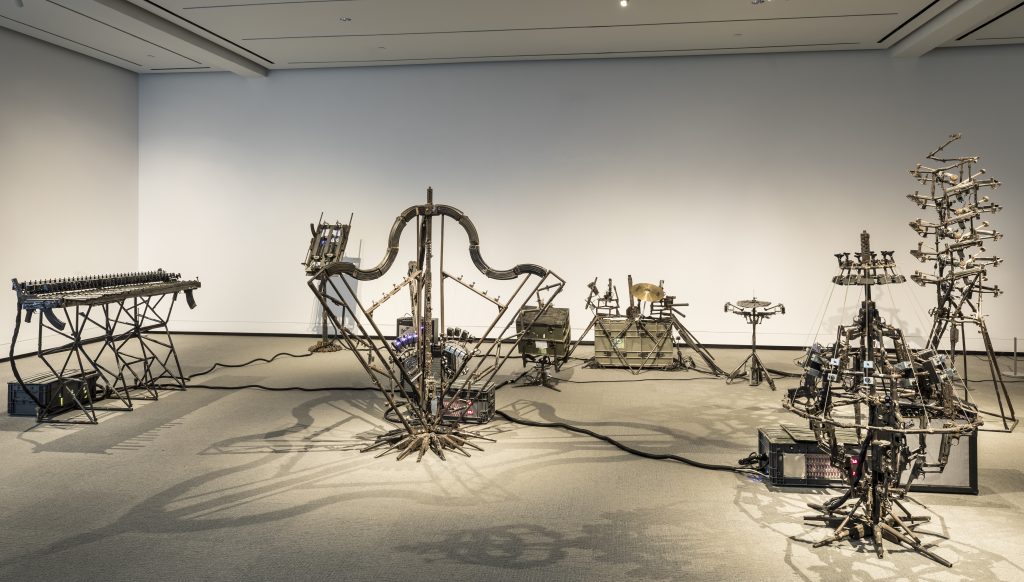

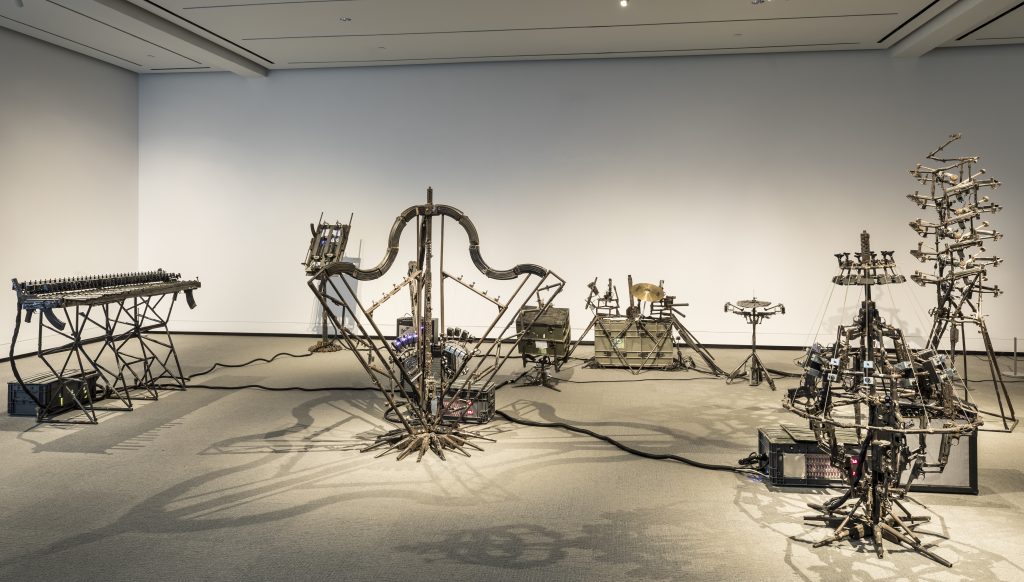

Pedro Reyes, Disarm Mechanized II, 2012–14, recycled metal from decommissioned weapons. On loan from the artist and Lisson Gallery, London. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Learn more about Pedro Reyes.

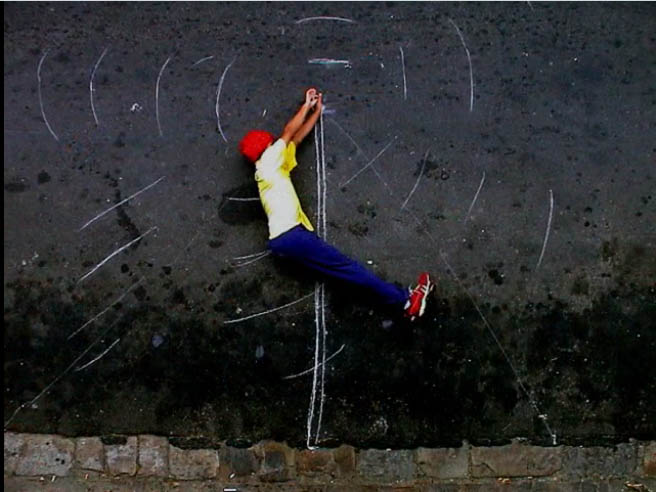

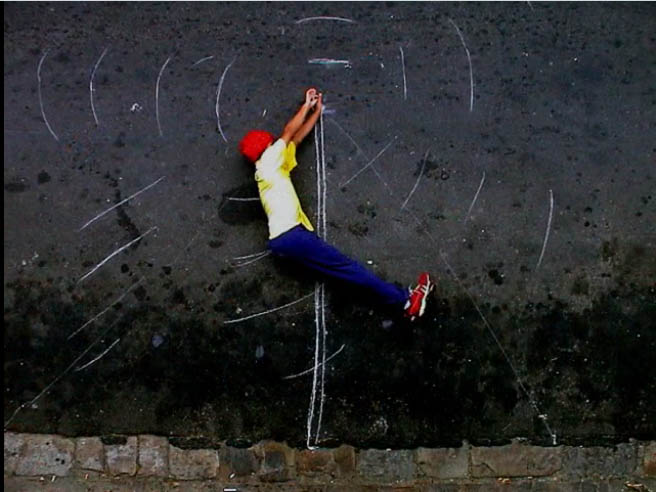

Robin Rhode

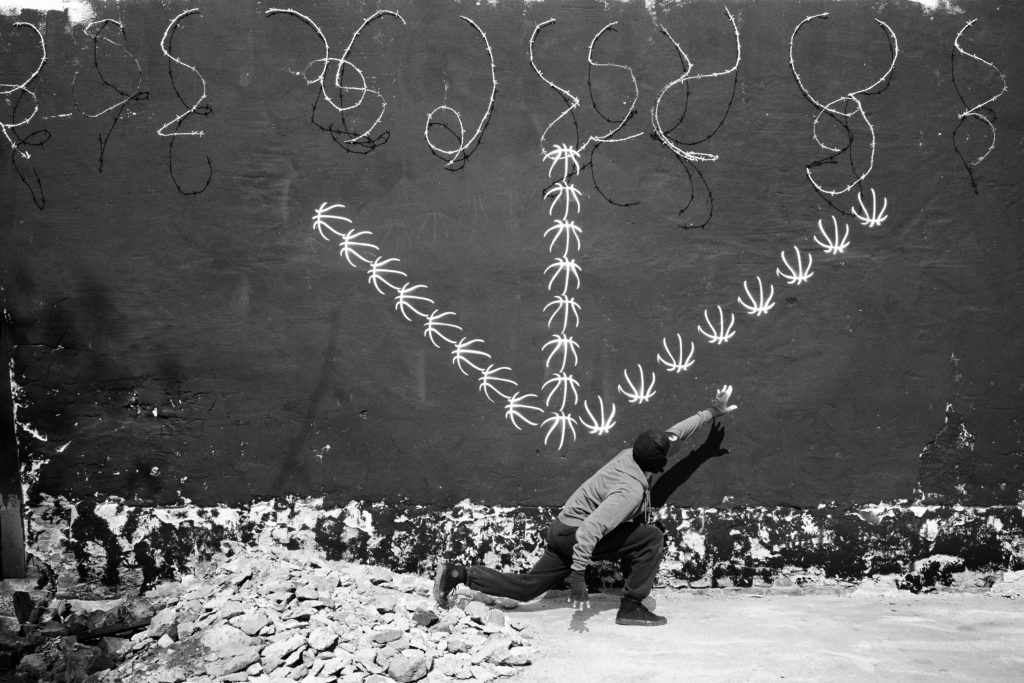

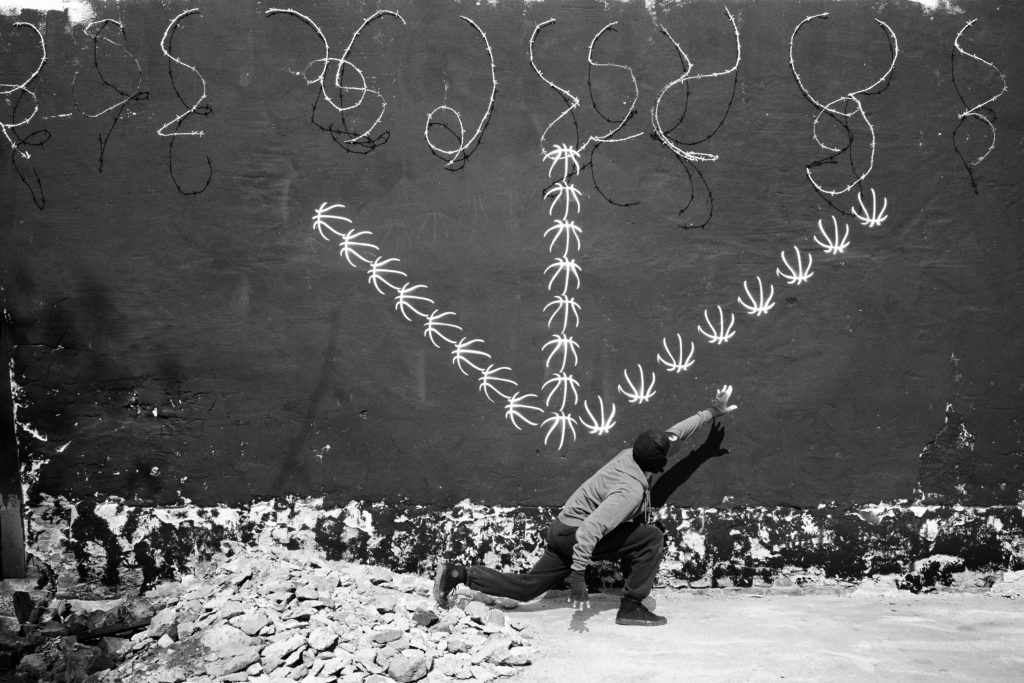

Robin Rhode, still from He Got Game, 2000, digital animation (1 minute). On loan from the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

Robin Rhode, detail of Four Plays, 2012–13, inkjet prints. On loan from the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

Robin Rhode, Double Dutch, 2016, chromogenic prints. On loan from the David and Gally Mayer Collection. Photo courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

Robin Rhode, See/Saw, 2002, digital animation (1 minute). On loan from the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

Robin Rhode, Street Gym, 2000–2004, digital animation (1 minute). On loan from the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

Learn more about Robin Rhode.

Roman Signer

Roman Signer, Kajak (Kayak), 2000, video (6 minutes). On loan from the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland.

Roman Signer, Punkt (Dot), 2006, video (2 minutes). On loan from the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland.

Roman Signer, Bürostuhl (Office Chair), 2006, video (1 minute). On loan from the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland.

Roman Signer, Rampe (Ramp), 2007, video (30 seconds). On loan from the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland.

Learn more about Roman Signer.

Gwen Smith

Gwen Smith, from the series The Yoda Project, 2002–17, sixteen inkjet printed photographs. On loan from the artist.

Learn more about Gwen Smith.

Angela Washko

Performing in Public: Ephemeral Actions in World of Warcraft, 2012–17, three-channel video installation. Courtesy of the artist.

Performing in Public: Four Years of Ephemeral Actions in World of Warcraft (A Tutorial), 2017, video (1 minute, 44 seconds). Courtesy of the artist.

The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft, 2012, video.

Nature, 2012

7 minutes

Healer, 2012

4 minutes

Playing A Girl, 2013

21 minutes

Red Shirts and Blue Shirts (The Gay Agenda), 2014

24 minutes

We Actually Met in World of Warcraft, 2015

52 minutes

Safety (Sea Change), 2015

44 minutes, 19 seconds

Courtesy of the artist.

/misplay, from The World of Warcraft Psychogeographical Association, 2015, video (1 hour, 15 minutes). Courtesy of the artist.

Learn more about Angela Washko.

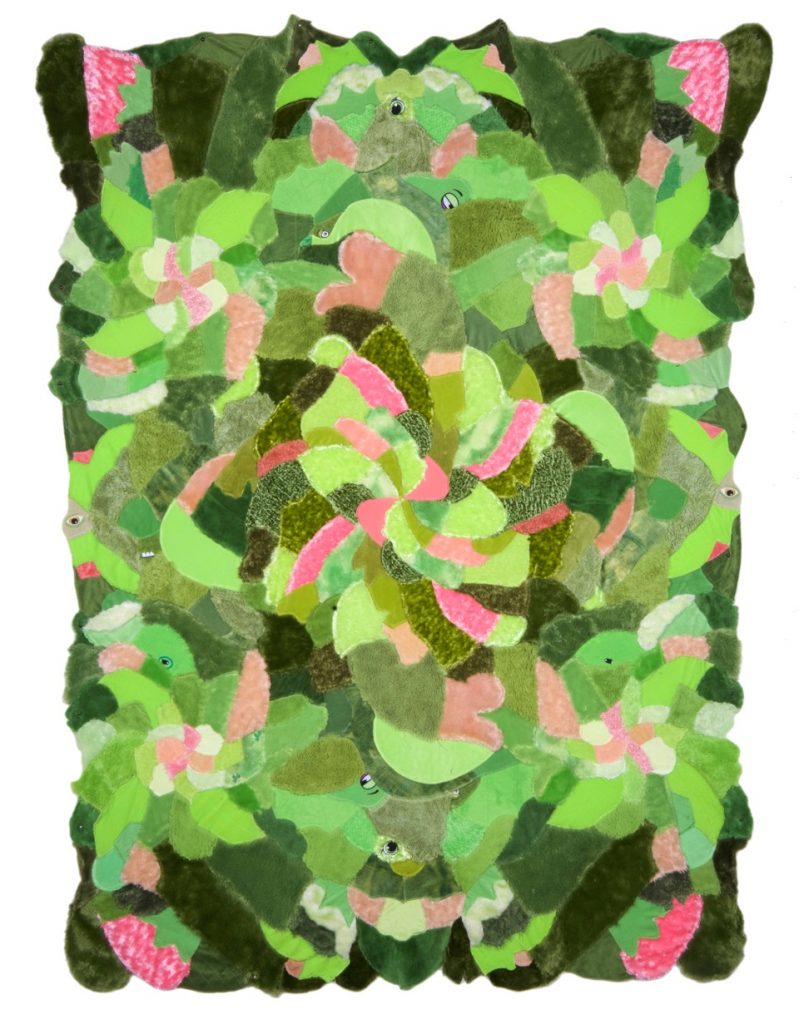

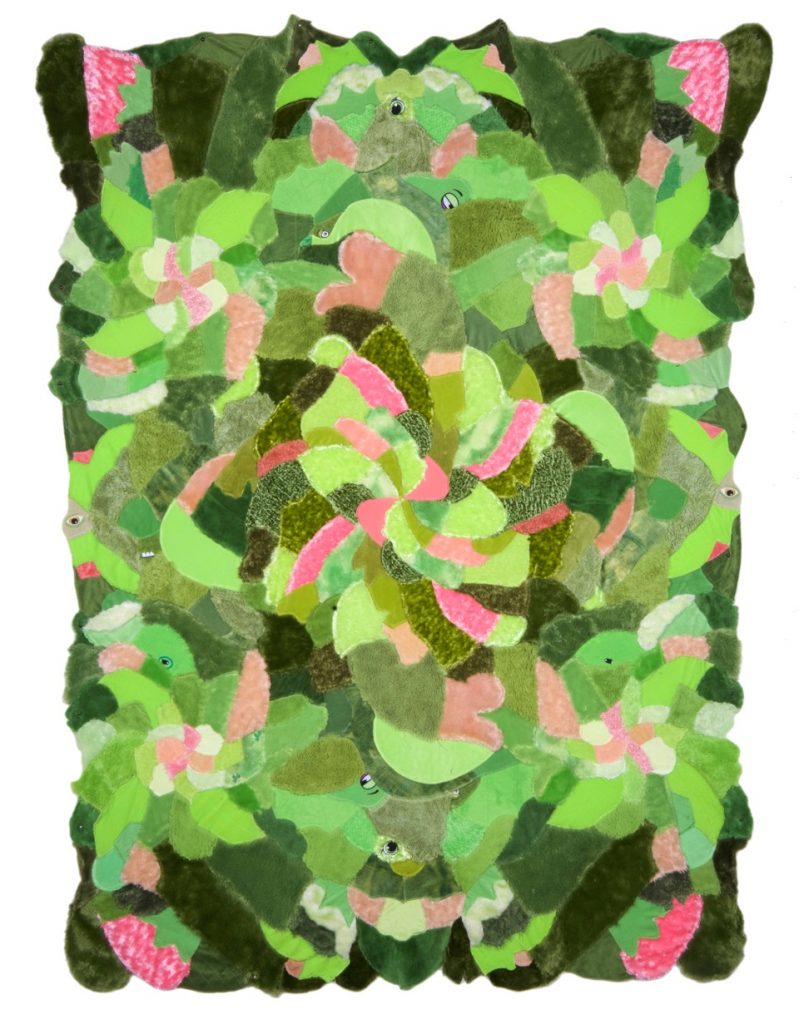

Agustina Woodgate

Agustina Woodgate, Rose Petals, 2010, stuffed animal toy skins. On loan from the Benjamin Feldman Collection. Courtesy of Spinello Projects, Miami.

Agustina Woodgate, Galaxy, 2010, stuffed animal toy skins. On loan from the Collection of Charles Coleman. Courtesy of Spinello Projects, Miami.

Agustina Woodgate, Royal, 2010, stuffed animal toy skins. On loan from the Collection of Alan Kluger and Amy Dean. Courtesy of Spinello Projects, Miami.

Agustina Woodgate, Peacock, 2010, stuffed animal toy skins. On loan from the artist and Spinello Projects. Courtesy of Spinello Projects, Miami.

Agustina Woodgate, Jardin Secreto, 2017, stuffed animal toy skins. On loan from Alex Fernandez-Casais. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Learn more about Agustina Woodgate.

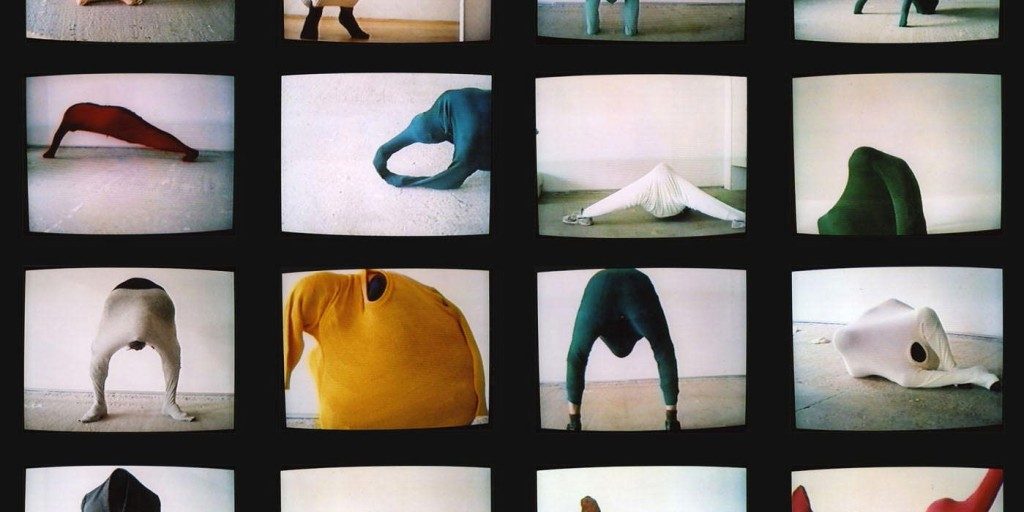

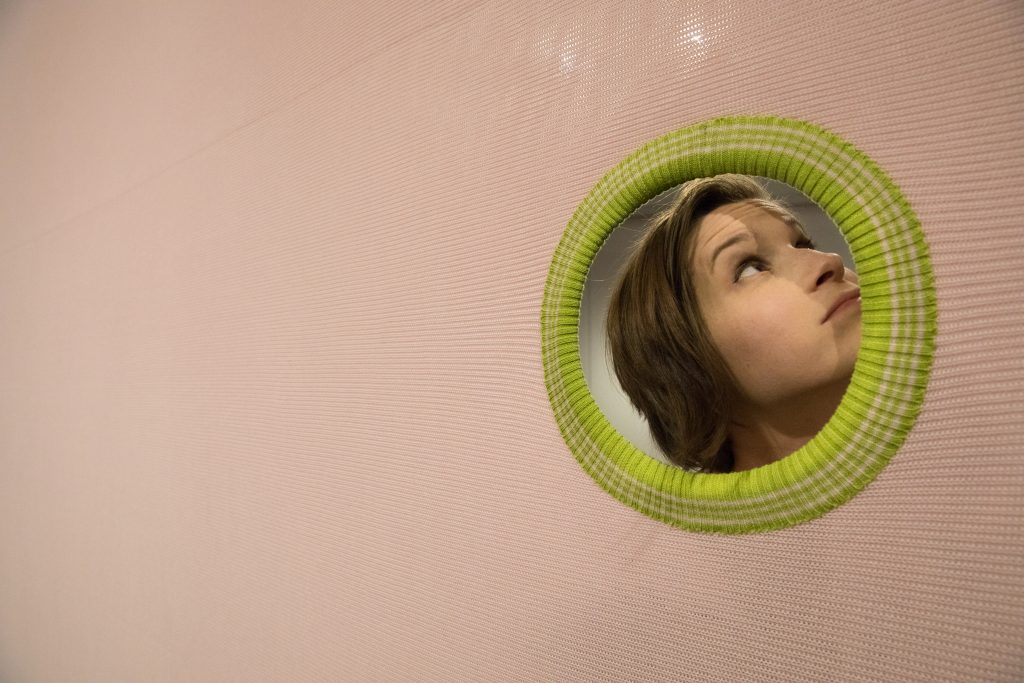

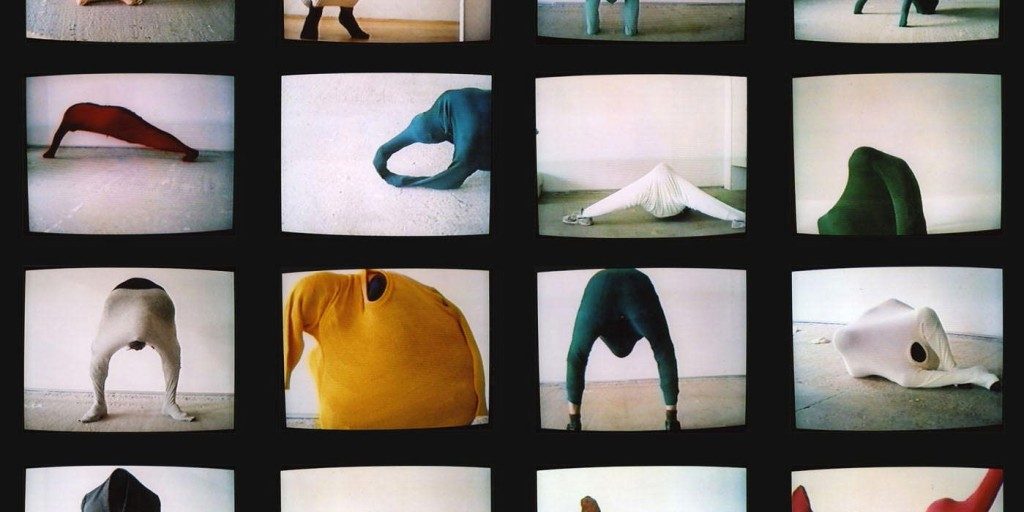

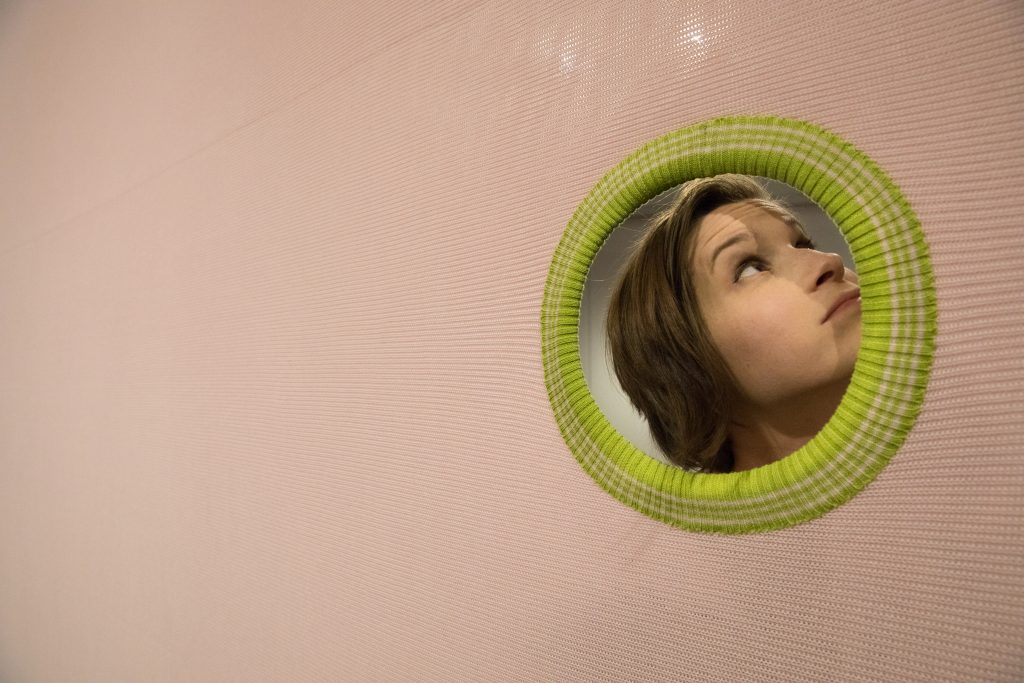

Erwin Wurm

Erwin Wurm, 59 Stellungen (59 Positions), 1992, video (20 minutes). On loan from Studio Erwin Wurm. Courtesy of Studio Erwin Wurm.

Erwin Wurm, Double Piece, 2002, from the series One Minute Sculptures, ongoing, sweater, instruction drawing, and pedestal, performed by the public. On loan from Studio Erwin Wurm. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Erwin Wurm, Organisation of Love, 2007, from the series One Minute Sculptures, ongoing, utensils, instruction drawings, and pedestal, performed by the public. On loan from Tate Modern. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Erwin Wurm, Metrum, 2015, from the series One Minute Sculptures, ongoing, shoes, instruction drawing, and pedestal, performed by the public. On loan from Studio Erwin Wurm. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Erwin Wurm, Sweater, pink, 2018, cotton-acrylic blend fabric and metal. On loan from Studio Erwin Wurm. Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

Learn more about Erwin Wurm.