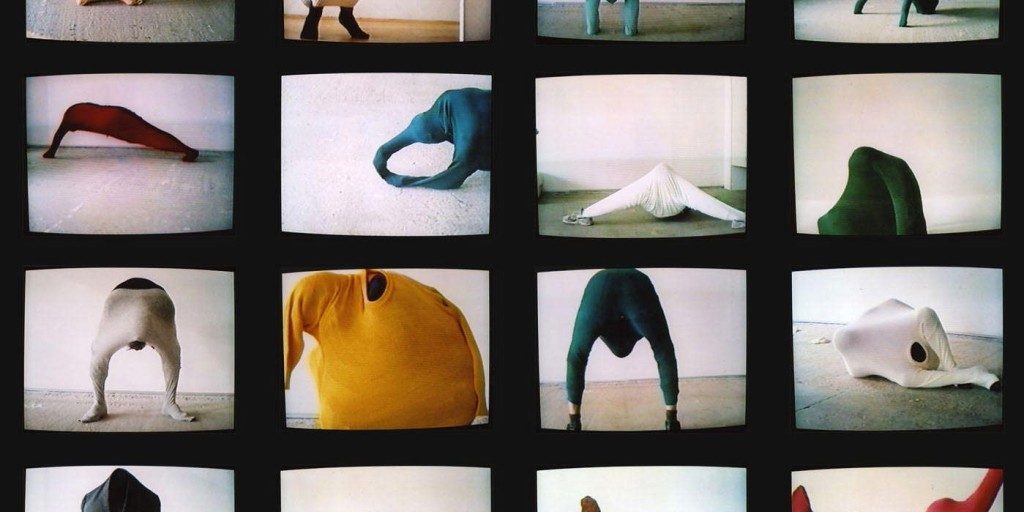

Long before social media made public embarrassment an everyday occurrence, Erwin Wurm’s One Minute Sculptures accomplished a similar feat by inviting people to play in public with common objects in uncommon ways.

By asking you to hold a pose for one minute, he pulls you out of the normal pace at which you view and consider art. In the process, you yourself become an artwork to be seen by others.

The instructions Wurm gives you often invite reflection on specific words or phrases, or, even in one case, you are invited to make up a piece of poetry to be recited while you pose.

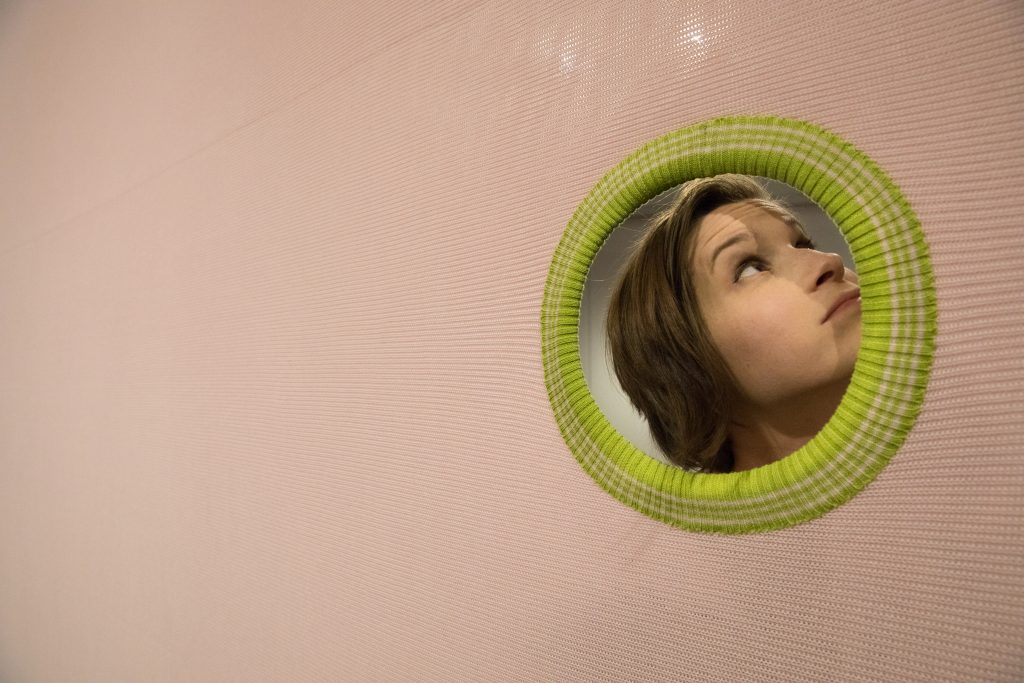

I performed a One Minute Sculpture at Wurm’s most recent show in New York a few months ago. His instructions invited me to lay my head on a plinth under a lamp and think about Epicurus, an ancient Greek philosopher. I knew that one of Epicurus’s ideas was about living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends, so I stood there, eyes closed in this public space, and thought about the many wonderful dinner parties that I have hosted in my home.

Some people only treat the One Minute Sculptures as an opportunity to laugh, but this misses something important. I was aware that by posing as I did I looked ridiculous, but the opportunity to step outside my normal behavior for a minute offered me a quiet moment of reflection and the work had a strangely calming effect on me.

How will you feel when you do a One Minute Sculpture?

Return to the artist page.