Is it possible for the world’s playful introduction to capitalism to transmit a new set of values? Writer Naomi Russo looks at Monopoly as an ideological tool.

Monopoly is a game in which anyone from a child to a grandma can become a ruthless property mogul. Sold in over 114 countries, the game was first commercially marketed as a success story of the American dream—a game invented, its packaging claimed, by an unemployed man for whom it made millions during the Great Depression. As a potent worldwide symbol for capitalism it has become so well recognized that during the Occupy London protest in 2011, an oversized Monopoly board sat outside St Paul’s Cathedral, featuring a destitute Rich Uncle Pennybags and attributed by many to famous street artist Banksy. The message to everyone was clear.

The young woman who originally invented the game, however, had far different ideals. Elizabeth Magie was inspired by her passion for the anti-monopolist economic theories of politician Henry George, and her desire to teach them to others in a simple, compelling way led her to develop The Landlord’s Game. In the words of her 1903 patent application, the game was designed “not only to afford amusement to the players, but to illustrate to them how under the present or prevailing system of land tenure, the landlord has an advantage over other enterprises.”

[Elizabeth] Magie struggled to generate commercial interest in her game and told that it was “too political” because of its anti-capitalist message.

The game had two sets of rules. One was similar to today’s Monopoly, while the other rewarded everyone and avoided monopolies. The game was featured in The Review in 1902, where Magie was quoted as saying, “There are those who argue that it may be a dangerous thing to teach children how they may thus get the advantage of their fellows, but let me tell you there are no fairer-minded beings in the world than our own little American children. Watch them in their play and see how quick they are [ . . . ] to cry, ‘No fair!’”

Nonetheless, Magie struggled to generate commercial interest in her game. Parker Brothers told her it was “too political,” most likely because of its length, complexity, and anti-capitalist message. The game was fairly didactic, and its values were at odds with the American economic system, not to mention with Parker Brothers, a company that stood to benefit from the very practices that the game sought to censure.

Still, the game had popular appeal and quickly evolved beyond Magie’s control. Some changes were slight, such as adaptations of the street names to the players’ neighborhoods, but others were radical. Perhaps the biggest change was the reversal of Magie’s original intent: as players created their own boards and rules, they focused on the elements that were the most exciting for them, and for non-Georgists, those were accumulating capital, building a real-estate empire, and dominating the market. This shift was so marked that the game came to be known colloquially as “Monopoly.”

Communist countries were quick to ban the game as a bad influence.

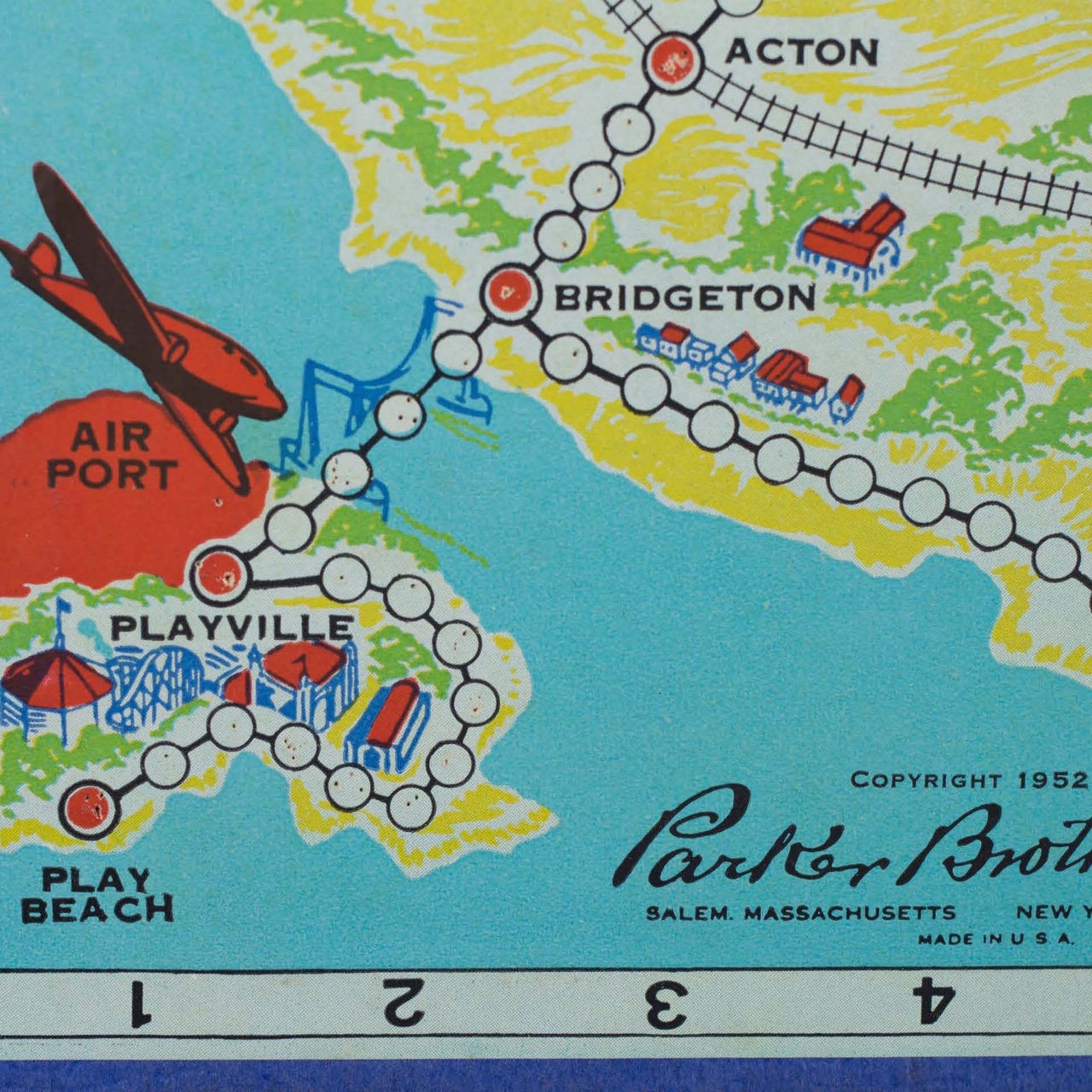

Monopoly was also the name used by Charles Darrow, an unemployed salesman, when he took the game to Parker Brothers, pretending it was his original invention. His version, stripped of Georgist ideals, was already selling well, so Parker Brothers decided to take a chance on it, and Monopoly’s popularity spread quickly across American and European nations.

Communist countries were quick to ban the game as a bad influence that spread capitalist values. In Cuba not only was the game banned, but the existing boards were destroyed after a direct 1959 ruling by the newly empowered Fidel Castro. Some countries such as Hungary adopted the alternative route of providing a replacement. After banning the Hungarian version of the game, Kapitaly, they began to sell a low-budget board game known as Gazdálkodj Okosan! Loosely translated as either “Economize Wisely,” or “Budget Shrewdly,” the game was far more politically correct, encouraging hard work and exercise with didactic Chance cards chastising bad behavior. “You have dirtied the street! Pay 10 forints,” read one such not-so-subtle card.

But as Professor David Stark writes, a state-sponsored game couldn’t usurp Monopoly as simply as that. He tells the story of a Hungarian friend, writing, “You did not need to be a nine-year-old dissident to see that Monopoly was the more exciting game,” and going on to explain that in his friend’s home Gazdálkodj Okosan! boards were turned over and used to form the basis of a homemade Kapitaly. The result was something of a hybrid born from remembered rules of Kapitaly, the cards of Gazdálkodj Okosan!, and the innovations of Hungarian children themselves.

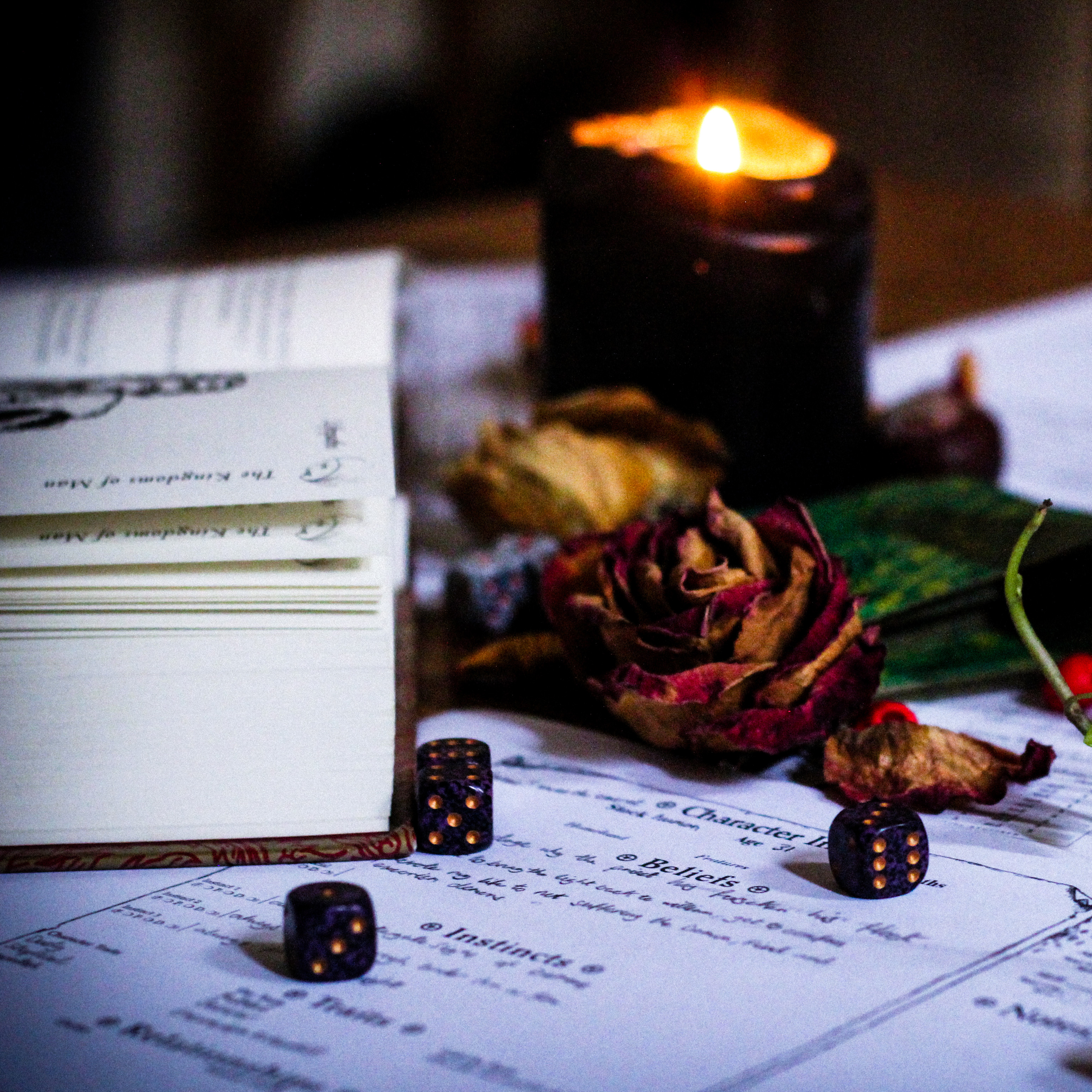

Monopoly spin-offs included a Hasidic version entitled Live Piously to Class Struggle, which aimed to show the superiority of Marxism.

The failure of Gazdálkodj Okosan! to impart its message has not discouraged others from creating their own politically motivated adaptations. In fact, the spin-offs by academics, artists, and others seem endless, from a Hasidic version entitled Live Piously that reinforces Satmar community values, to Class Struggle, which aims to show the superiority of Marxism. None of these adaptions have had anywhere near the success of Monopoly. Their small sales suggest that they mostly remain within their community rather than spreading their values more widely.

If games can transmit values, however, why did Magie’s version fail while Darrow’s succeeded? As Keith Devlin, the “NPR Math Guy,” told KQED ’s Mindshift, “Games are just simulators with an internal incentive structure.” And The Landlord’s Game lacks real incentive. As professors Dr. Mary Flanagan and Dr. Helen Nissenbaum discuss in Values at Play in Digital Games, students at Virginia Tech who played both versions found that while The Landlord’s Game made its point, Monopoly was much more fun.

So are users learning to be ruthless capitalists when they play Monopoly? Research fellow Dr. Marcus Carter says probably not, arguing that “despite the arguments and allegations of betrayal Monopoly is likely to cause in homes this Christmas, its morality is as unrealistic as that in Grand Theft Auto. Players are granted no moral choice whether or not to bankrupt their opponents and consequently, there is little moral involvement.”

A social psychologist found that Monopoly can be set up to simulate moral decision processes.

On the other hand, social psychologist Paul Piff believes that Monopoly might be able to be used to expose moral codes or ethics. Piff uses rigged games, in which the rules are changed to make one player unbeatably wealthy, to reveal what he believes his earlier research has shown: that wealthier people tend to lack empathy. His studies with rigged games showed that the person given all the advantages quickly became accustomed to them and played ruthlessly, feeling little to no regard for the other less fortunate player. His conclusions supported his continued work on the so-called “empathy gap,” but they also reveal two things about the game: first, that Monopoly can be set up to simulate moral decision processes, but second and more importantly, that those morals are affected by the rigged circumstances of the game. In other words, how people play isn’t necessarily how they act in the real world, but it is affected by the type of player the game sets them up to become. There is no evidence that they continue to act in such a fashion after they stop playing that role.

Flanagan contends that “Monopoly successfully imparts the values of competition, individual wealth, and exclusivity,” but it’s worth noting that these values weren’t a critique of the society in which the game evolved, nor of our society today, but rather a reflection of it. This makes it hard to know whether Monopoly really encourages such values, or simply represents the values its players already have.

So can games like Monopoly work to transmit new values? The more than 200 versions would seem to suggest that many believe so. But the lesson from the many adaptations that have failed to catch on, and from Magie’s original game, is clear: a game can be used to spread a message, but for it to reach beyond a limited target audience, first and foremost, it must be fun. ♦

“Propagandopoly” originally appeared in Works That Work, No 9. Photo credit: Courtesy of Thomas Forsyth, LandlordsGame.info.