Writer and critic Katherine Cross examines the fundamental truths—and benefits—of identity in role-playing games and how they provide the chance to reveal players’ true natures.

Look at the back of the box for any video game and you’ll find a bullet-pointed list of features. “Pulse pounding dungeons,” “hyper realistic graphics,” “exciting multiplayer.” The real joy of gaming, however, comes from what’s silently lurking between those points. They don’t tell you about breaking up loveless marriages, changing your gender, finding the love of your life, or coming out as queer.

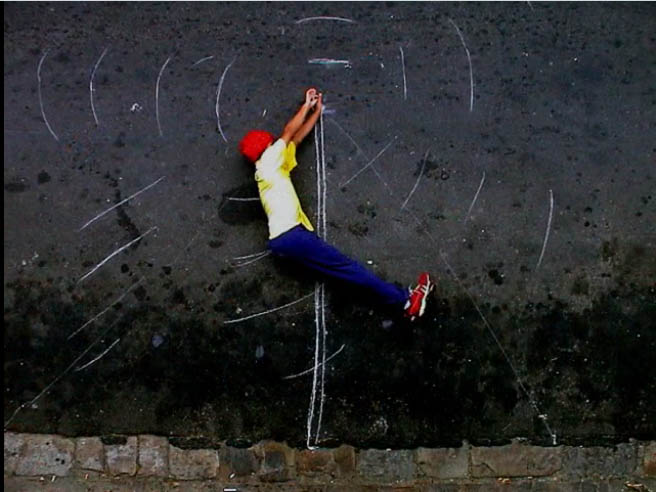

Video games are a mirror in which we may see an unfamiliar reflection. They entice players with the promise of an ideal self—the heroic warrior, space marine, or Chosen One who can save the world with countless magic powers that Ordinary You can only dream of. But every person’s “digital ideal” scatter-plots around the mean as a proliferation of perfected, experimental selves who will invariably stray from the intentions of game developers. I’ll never forget how World of Warcraft sparked an affair between two women I gamed with, one in Australia, the other in Hawaii. I never knew what became of them, but the game became intrusively and inescapably real for them both.

The real adventure is what transpires beyond the promises on the back of the box.

That’s always been the trick, you see. Video games, especially those that take place online and throw us all together in some virtual arena, aren’t just games. The game, the ludic matter of scoring points and showing mastery of your skills, becomes a mere excuse for everything not covered by an ESRB rating. The real adventure, often as not, is what transpires beyond the promises on the back of the box. In my time as an online gamer I’ve taken on the role of therapist, talking people I’ve never met down from the ledge of suicide. Imagine my character running through a forest, gathering herbs for her Alchemy skill, and in every spare moment I’m typing out messages to a friend, letting her vent and cry, while sending her missives that I hope will make her hate herself less.

When you play a game like this, the gulf between who you are and who you want to be becomes painfully evident—and yet it’s the pocket of netherspace you dwell in. It’s a mixture of inadequacy, thwarted ambition, and innervating eros that seizes every ounce of your attention. That mixture is alcoholic in its vintage; if booze is liquid courage, the frisson of gaming is a kind of digital courage. What people do with that courage, as is so often the case with its liquid variety, varies widely. Sometimes the inadequacy wracks you and becomes the only thing you know; this becomes an impetus to abuse, to use the illusion of power granted by the game to become a raging wanker whose license is the very concept of play. “It’s just a game, don’t be offended,” or “It’s just words on a screen,” they might say. Such people, almost invariably, try to bring cruel bigoted abuse and sexual harassment under the umbrella of gaming culture. Someone says you can’t shoot straight because you’re a girl? That’s just “trash talk,” the currency of competitive gaming’s realm.

The gap between who you are and who you want to be causes a monstrous mutation; you take it out on anyone in reach, battering them in the hope of feeling strong and powerful because you need one more hit of that elixir, one more shot to the arm in order to feel like a Big Man (and it is so often men who fall prey to this). This is the world in which GamerGate—a harassment campaign spawned by reactionary, self-identified “gamers” against women and queer people in the gaming industry, to purge us and our “corruption”—seemed to prefigure the resurgence of the wider “alt-right”; where the Ubermenschen lifestyle promised by gaming’s consumer-king culture has inadvertently become a fertile recruiting ground for actual neo-Nazis.

It’s hard not to feel despair at this. But there’s more to this world than its darkness, even if that’s all we can see now. There is, and always has been, another reality in the virtual. It’s the reality of the young transgender woman who finds her voice as a woman thanks to videogaming, or the reality of the game developer who speaks in a register only a game can fully express; the queer indie developer whose use of new game development tools allows her to tell a story that would never make it past the gatekeepers of traditional publishing. For all their artifice, these interactive realms have a way of drawing the truth from us, dissolving closet doors and puritanical inhibitions in ways that are redolent of underground scenes. But the pulse of the club or burr of the speakeasy are replaced instead with visions of the fantastical, which for all their blatant falsehood make it strangely impossible to lie to yourself. What you play, especially when you’re given a wide choice, says a lot about your innermost yearnings.

You know that insufferable question everyone gets asked at job interviews? “If you could have one superpower, what would it be?” Supposedly, the answer reveals a lot about you. Super strength indicates, perhaps, an aggressive personality; invisibility may suggest a subtler, shyer one. But with the act of roleplaying in a video game you’re surrounded by people you don’t really have to impress with your answer. It instead takes flight amid a carnival of other answers, loudly competing for space in the digital crowd. As a consequence, it says a good deal more about some aspect of you.

I had discovered what it was that I was really getting out of all my playing: a chance to be my truest self.

Some games play this to the hilt. Kitfox Games’ Moon Hunters—an enchanting prehistorical fantasy where you discover what happened to a missing moon goddess—marketed itself as a “co-op personality test RPG,” where your character’s choices added up to some truth about the player, writ large in an in-game constellation. Most games don’t embrace this so openly, however, leaving it to you to discover on your own just what it is that compels you to role-play a certain kind of character.

But the next time you get really into a game, especially one that allows you a wide degree of latitude in customizing the character you play, it’s worth asking yourself what you’re really playing with here. For my part, my World of Warcraft days drew to a close not long after I came out. I went from twelve-hour days in the game to barely being able to log in. I had discovered what it was that I was really getting out of all my grinding, raiding, and farming: a chance to be my truest self. As soon as I found a way to do it in the physical world I had less need of a digital facsimile. I owe gaming that much—and I owe it to the medium to remember the best of its potential, even in these dark days. ♦

(Image credit: Still from World of Warcraft courtesy Martin Chung via Flickr.)