In 2003, a posse of artists, programmers, and musicians raised on first-generation computers and early programming languages embarked on a cross-country house tour. Los Angeles Times music writer Randall Roberts tells the story, including the details on a stop at his home.

A few years after graduating from college, the dozen-odd creators included, at various stops, an outfit known as the BEIGE Programming Ensemble, the electronic noise group Extreme Animals, whose screaming singer Jacob Ciocci was a co-founder of the Paper Rad artist collective, the elusive stunt-mixer who performed as DJ Shoulders, and ghetto-tech producer Bitch Ass Darius. They dubbed it “The Summer of HTML.”

The pitch for the series of events was this: “on this tour we will be doing live HTML performances as well as audio music nintendo hacker adventures audio rave nightmares and video showings of our cartoons. We are going to make new webpages and put them on a cool webpage.” Like a package concert tour but minus the concert part, the two week expedition took them to galleries and performance spaces in New York, Boston, Chicago, Milwaukee, and elsewhere. In St. Louis, the tour landed at my house, a.k.a. the Louis Hartoebben Contemporary Art Museum, named in honor of the retired fireman who had sold me the building for a song.

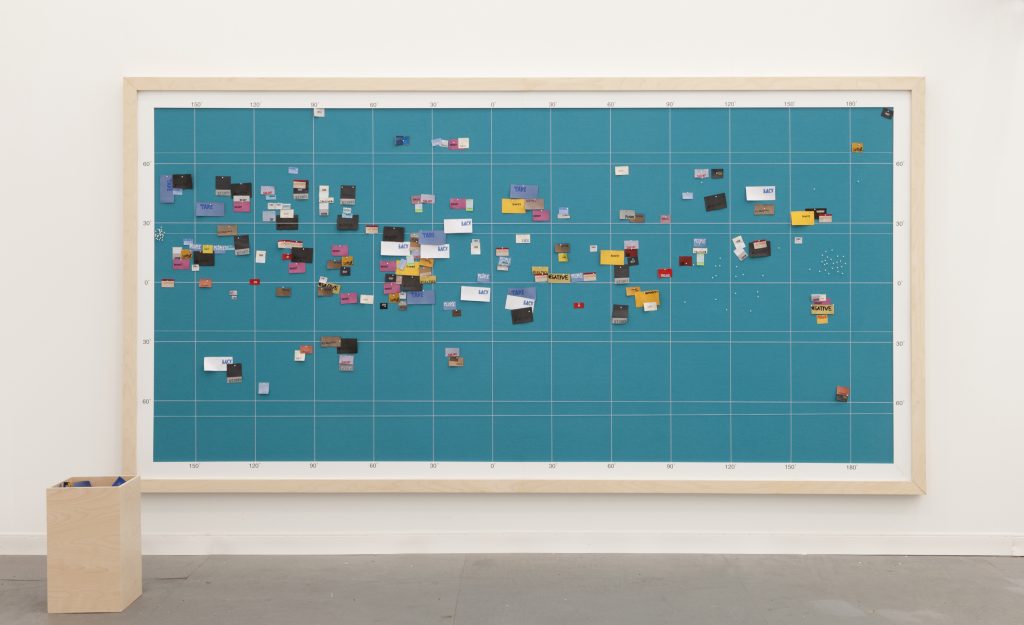

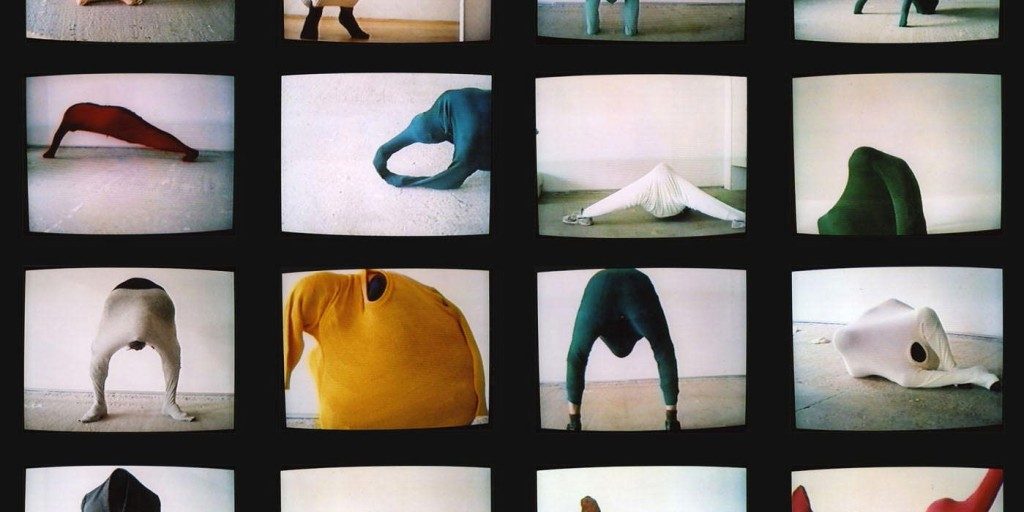

The BEIGE Programming Ensemble, which featured multimedia artists Cory Arcangel and Paul B. Davis, sound engineer Joseph Bonn, and high-level programmer and DJ Joseph Beuckman, had recently issued a record called The 8-Bit Construction Set: Commodore 64 vs. Atari 2600, an interactive 12-inch “DJ kit” on which they had transferred a few dozen of their programmed locked-groove beats. The sounds on one side were programmed using a Commodore 64; the B-side on an Atari 2600, each of which had its own distinctive synthesized tones. When employed by a DJ with a pair of turntables, a mixer, and two copies of the record, the looped grooves served as building blocks—the construction set—to create on-the-spot, 133 beats-per-minute, 8-bit tracks. Place the needle in the groove and rather than progressing through a song as it glides toward the center, the stylus moves in an infinite circle, looping whatever recorded sound is contained therein. The record also featured sound samples of Atari- and C64-related tones and two wildly complex original Davis compositions, “Dollars” and “Saucemaster.” The inner band on each side was a data track, or stored program, that—when taped onto cassette and loaded into a computer tape drive connected to a computer—ran a Roland 303 emulator.

Raised on first- and second-generation computers and gaming consoles, BEIGE was exploring ways to harness interfaces and their low-level programming languages in service of visual and sonic art. Most famously, Arcangel and Davis, both students at Oberlin (along with Bonn, who is now an accomplished music editor for film and just concluded work on Star Wars: The Last Jedi), were cracking open Nintendo cartridges and reprogramming the chips to create striking video game vistas and blippy 8-bit music scores.

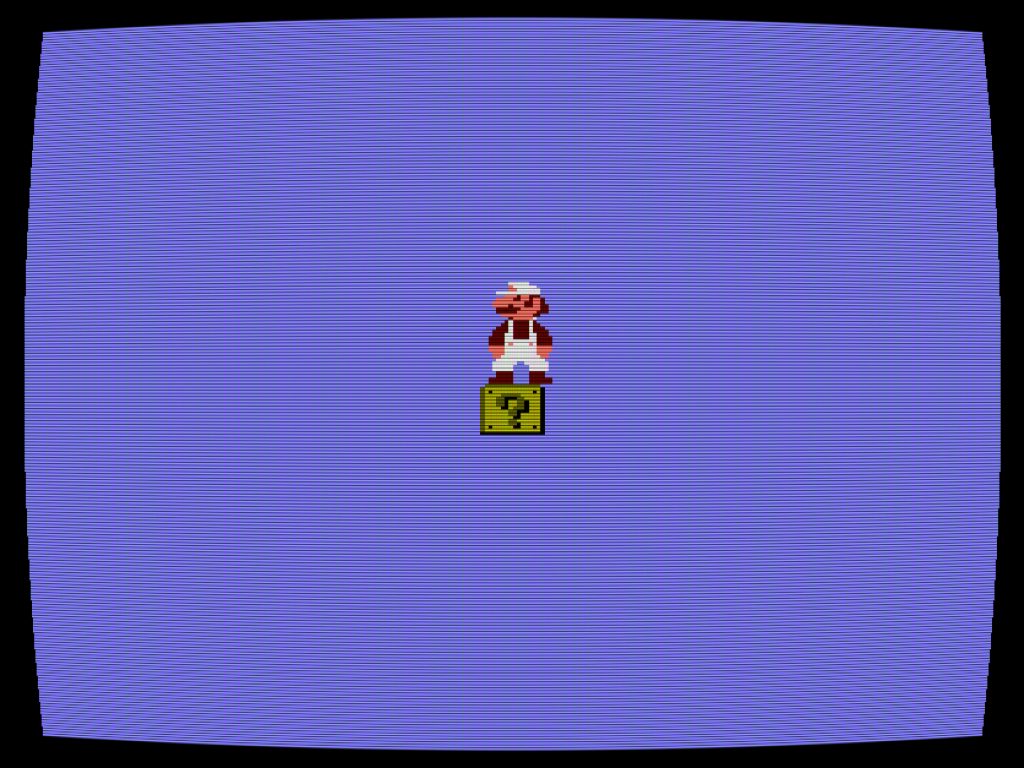

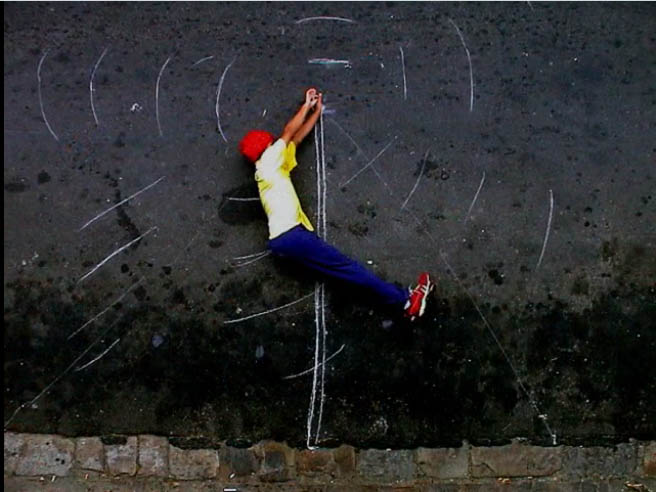

“Arcangel had recently unveiled his acclaimed hack Super Mario Clouds, and offered a step-by-step tutorial.”

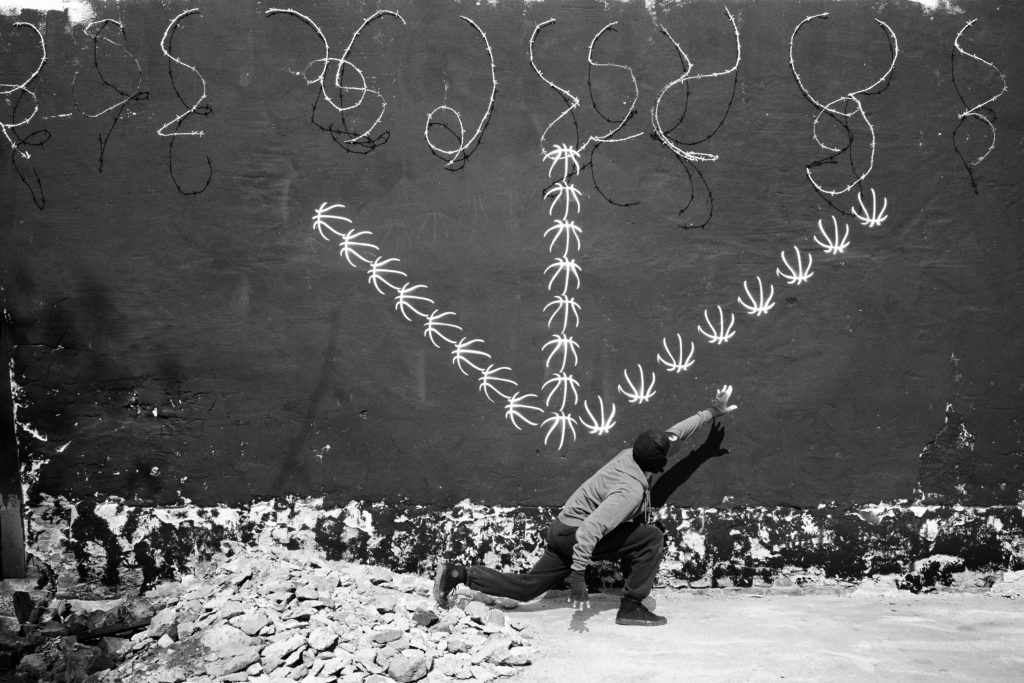

Along with Beuckman, who was living, studying, and spinning records in St. Louis under the name DJ Cougar Shuttle, the quartet weren’t a musical group per se. “It was barely a band,” Arcangel told me during a recent conversation. “I always thought of it more like a crew—like a graffiti crew or a drum ‘n bass crew.”

During the performance at the Hartoebben, Arcangel delivered a PowerPoint demonstration that included a detailed explanation for how he and Davis hacked Nintendo cartridges and messed with the innards. Arcangel had recently unveiled his acclaimed hack Super Mario Clouds, and offered a step-by-step tutorial. Davis teamed with the mysterious spinner DJ Shoulders to tear through a set that mixed Detroit techno – a lot of Underground Resistance, if I recall correctly—and improvised Construction Set compositions featuring squiggly-sounding acid house tones and Atari and C64 samples. Extreme Animals—Ciocci and David Wightman (a.k.a. DJ George Costanza)—performed a frantic set of synth noise. Ciocci also screened short Paper Rad films created by him, his sister Jessica Ciocci, and the visual artist Ben Jones.

BEIGE seldom “played” music as a band would, either on the tour or any other time. “It was even more disparate, which is more in line I think with how one would operate over a computer,” Arcangel said, describing the process as “more electronic or something, where we were never all in the same place at the same time.”

Now an artist and lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, Davis told me that when he was working on the already anachronistic machines in the early ’00s, he was thinking about “the explosion of the internet and how it often felt like the interfaces were leading you where whoever designed the interface wanted you to go, rather than, from a programming perspective, where you might tell the computer what to do.”

The video game character Mario might seem to be content to race through his programmed course upon boot-up, but he was locked in a Sisyphean cycle. What if, pondered ensemble members, Mario and his gaming environment could be freed from the shackles of the creator’s programming?

One piece that Davis programmed featured Mario set against a black background, staring to the side. Above him in Nintendo-era digital lettering were the words, “Now I just stand here silently among data that grows cold.” Arcangel said that when he, Davis, Bonn, and Beuckman were working on the record, he’d just switched majors, was overwhelmed with schoolwork, and was making beats onto a Commodore 64 at off hours. Working with what the artist described with affection as “a beautiful, simple tracker that just showed a screen full of hexadecimals” called Future Composer 4.0, he built loops one coded line at a time. “The game was to get these really raw sounds,” Arcangel said. “Just make these really nasty, raw loops.” It didn’t hurt that the record was mastered in Detroit by legendary techno engineer Ron Murphy, who made the loops sound gritty and deep.

“Working with what the artist described with affection as “a beautiful, simple tracker that just showed a screen full of hexadecimals” he built loops one coded line at a time.”

In addition to being an awesome object, Davis stressed that aspects how they made beats for the 8-Bit Construction Set were, for him, “slightly political in their response, I think, to the way I saw computer usage progressing in society at the time.” Describing “anti-reverse-engineering and surveillance laws then coming into effect,” Davis recalls being critical of the corporatization of programming. Now, he said, “It’s like par for the course. No one even thinks about it. It’s understood that that’s how these devices are in our lives. They’re not supposed to be investigated in any way.”

Simultaneously, Arcangel said, the goals of the project and the tour “were very unclear, but that was part of the fun. Nothing was planned. There was just a lot of energy, and that is kind of what sustained the enterprise. Especially with the tour. You saw the tour. It was chaotic. You couldn’t do it if you’re forty.” ♦

Photo credits: Feature image of Cory Arcangel’s Totally Fucked, 2003, courtesy of the artist. Marginal images of the 8-Bit Construction Set in St. Louis and posters, courtesy of Randall Roberts. Lower left image by and courtesy David Wightman (Paper Rad).