PLAY spurs productivity.

PLAY is a catalyst for creativity.

PLAY is an escape from conformity.

PLAY reinvents the rules.

PLAY empowers the players.

PLAY stimulates innovation.

PLAY enables exploration.

PLAY is a response to uncertainty.

PLAY rewards misbehavior.

PLAY negotiates conflict.

PLAY resists productivity.

PLAY is _______________.

What’s your take on the MANIFESTO?

#PEMplaytime

Month: September 2017

The Trouble with Losing at Chess: An Essay

In the first of a two-part essay, writer and tech philosopher Tom Chatfield looks at an early progenitor of artificial intelligence.

In 1770, the inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen displayed a mechanical marvel to the Viennese court. Watched by the Archduchess Maria Theresa and her entourage, he opened the doors of a wooden cabinet four feet long, three feet high and just over two feet deep, illuminating its interior by candlelight to display glistening cogs and gears. Seated at the cabinet was a life-size model of a man in Turkish dress—a turban and fur-trimmed robe. In front of the Turk, on top of the cabinet, was a chessboard.

Kempelen closed his cabinet and asked for a volunteer to play a game of chess against the Turk. It was astonishing request. Finely crafted automata had been entertaining royalty for centuries, but the idea that one might undertake an intellectual task such as chess was inconceivable—something for the realm of magic rather than engineering. This was precisely the point. Six months earlier, Kempelen had claimed to the Archduchess that he was utterly unimpressed by magic shows, and could build something far more marvelous himself. The Turk was his proof.

Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, the first volunteer, approached the table and received his instructions: the machine would play white and go first; he must ensure he placed his pieces on the centre of each square. The count agreed, Kempelen produced a key and wound up his clockwork champion, and with a grinding of gears the match began. To its audience’s astonishment, the machine did indeed play, twitching its head in apparent thought before reaching out to move piece after piece. Within an hour, the Count had been defeated, as were almost all the Turk’s opponents during its first years of growing renown in Vienna.

Humanity, for so long self-defined as the pinnacle of nature, had begun to feel less than mighty in the face of its own creations.

A decade later, Maria Theresa’s son, Archduke Joseph II, asked Kempelen to bring his creation to a wider public. The Turk visited Paris, London and Germany, inviting fervent speculation wherever it went. Among its losing opponents were Benjamin Franklin, visiting Paris in 1783, and—under its second owner after Kempelen’s death—the emperor Napoleon in 1809. Napoleon tested the machine with illegal moves, only to see the Turk sweep the pieces off the board in apparent protest.

It was, of course, a fraud—a magic trick masquerading as a mechanism. Behind the cogs and gears lay a secret compartment, from within which a lithe grandmaster could follow the game via magnets attached to the underside of the board, moving the Turk’s arm through a system of levers. In his book The Turk, the British author Tom Standage tells the story in captivating detail—noting that even the unmasking of its workings in the 1820s scarcely diminished the age’s fascination with the Turk. The image of man and machine locked in combat across the chessboard was simply too perfect—and too perfectly matched to a growing unease around technology’s usurpation of human terrain.

Humanity, for so long self-defined as the pinnacle of nature, had begun to feel less than mighty in the face of its own creations. The Industrial Revolution brought fire and steam as well as clockwork into the public imagination, together with anxieties that have echoed across society since: of human redundancy in the face of automation, and human seduction by new kinds of power.

Kempelen’s desire to make not simply a machine but also a kind of magic trick was no accident. The Turk set out to inspire belief, and had picked the perfect arena for persuasion: a bounded zone within which complex questions of ability and intellect were reduced to a single dimension. Sitting down opposite a modern reconstruction of the Turk in Los Angeles, Standage found himself surprised by how “remarkably compelling” the illusion remained, speaking to “its spectators’ deep-seated desire to be deceived.” Tools that can master a task are one thing—but it’s when they are also able to engage and enthrall that enchantment begins.

Long before digital computers had gained a genuine mastery of chess, one man devised a twentieth-century game with some remarkable similarities to Kempelen’s scenario. “I propose to consider the question, ‘Can machines think?'” wrote Alan Turing in his 1950 paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” The trouble with such a question, he observed, was that answering it was likely to involve splitting hairs over the meaning of the words “machine” and “think.” Thus, he continued, “I shall replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words. The new form of the problem can be described in terms of a game which we call the ‘imitation game.’”

Turing’s imitation game entailed a conversation between a human tester and two hidden parties, each communicating with the tester via typed messages. One hidden party would be human, the other a machine. If a machine could communicate in this way, such that the human tester could not tell which of their interlocutors was machine or human, then the machine would have triumphed. “The game may perhaps be criticized,” Turing noted, “on the ground that the odds are weighted too heavily against the machine. If the man were to try and pretend to be the machine he would clearly make a very poor showing. He would be given away at once by slowness and inaccuracy in arithmetic.” Pretending to be human meant embracing limitations as much as showing strengths.

The answer was likely to involve splitting hairs over the meaning of the words “machine” and “think.”

Turing’s thought experiment suggested that, if the impression created were robust enough, the means of its achievement became irrelevant. If everyone could be fooled all the time, whatever was “really” going on inside the box ceased to matter. A game was the perfect test of intelligence precisely because it abandoned definitions in place of a challenge that could be passed or failed, as well as endlessly restaged. By excluding the world in favor of a staged performance, it made the ineffable conceivable.

Turing’s game is today played for real during the annual Loebner Prize, which since 1991 has promised $25,000 for the first AI that judges cannot distinguish from an actual human—and that convinces its judges that their other, human conversation partner must be a machine. No machine has got close to winning this award, but competing AIs are ranked in order of achievement. To the frustration of many AI specialists, the most successful chatbots tend to use tricks based on stock responses and emotional impact rather than understanding. Much like the grandly dressed Turk two centuries ago, the setup rewards the use of distractions and deceits: bogus bios, pre-programmed typing errors, hesitations, colloquialisms and insults. To win an imitation game, in certain circumstances at least, is not so much about perfect reproduction as targeted mimicry.

This is echoed in the world at large. If and when people are fooled by modern AIs, something more like stage magic than engineering is going on—a fact emphasize by the importance that companies like Apple, Amazon, and Google attach to quirky features which make their creations more appealing. Ask Amazon’s digital personal assistant Alexa whether “she” can pass the Turing test and you’ll get the reply, “I don’t need to pass that. I am not pretending to be human.” Ask Apple’s Siri if “she” believes in God and you’ll be told, “I would ask that you address your spiritual questions to someone more qualified to comment. Ideally, a human.” The responses have been pre-scripted both to amuse and to disarm. They’re meant to fool us into perceiving not intelligence but innocence—products too charming and too useful to provoke any deeper anxiety. The game is not what it claims to be.

Check out part two of Tom Chatfield’s essay here.

Tilt: An Essay

Digital devotee Virginia Heffernan finds herself seduced by pinball and the wonders of the arcade.

In the middle of the journey of life, I found myself astray in a vast executive conference center, my pulse ramping up as it can during weekends of airports, strangers, and vertiginous hotels cold as meat lockers. I was trying to avoid a tech conference. I aimed to look intent on something, improvising a straight path, though all I was really looking for was an armchair where I could be alone with my phone.

Down one hall and up the next was nothing but evidence of other conferences: still lifes of coffee and KIND bars flanked by signs announcing plenary and breakout sessions on subjects ranging from—well, the one I remember was “Rendering.” Horses to glue. But it wasn’t as simple as that; rendering had made giant strides.

At last I found what it turned out I’d been looking for all along: an arcade. Dated, neglected, this oddly shaped chamber, lined in cola-stained linoleum contained maybe seven gaming machines, three of them lightless and lifeless. It was a floor down, visible through a slanted window, two glass doors away from a swimming pool. I zagged around and burst into it.

Over the last twenty-five years, the Internet has doggedly modeled for us a strange but familiar truth.

A vintage machine offering the holy trinity of nostalgia—Ms. Pac Man, Asteroids, and Centipede—presented itself as melancholia too picked over. I admired a bulky game with a low-slung vinyl seat that turned out to be an entry in the Cruisin’ World driving-game series. In this one, you could zoom perilously through the gold-beige light of the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in Paris, where Princess Diana died.

And then there was a pinball game. I love pinball. I was dressed in a sleeveless khaki summer dress and pumps for my own morning plenary session, a panel on the scourge of ad-blocking software for business. But I decided I’d play pinball better out of heels, so I kicked them off. Bare feet allowed the minor transgression of naked soles on cold linoleum sticky with RC Cola, a welcome taste of the unsanitary in a prison of antisepsis.

A clattery token machine took my $10 bill and returned fistfuls of chances. I sized up the game. We’d be at it a long time. The conference session I was skipping (“Does Hollywood Need a Hard Reboot?”) faded from memory. Token in. The swallowing sound of the game accepting my opening sally—not fighting it—and coming alive, suggested that the pinball table, with its Monopoly theme, had been waiting for me. Presiding over my detour to belled and blinking Atlantic City was Parker Brothers’ icon of cheerful avarice, J. P. Morgan made cute: Rich Uncle Pennybags.

My fathom-long body, as the Buddha called it, returned to me as I stood before Pennybags. It had been gone a long time. Monopoly-themed pinball would seem to be an unlikely agent for this physical homecoming, but those homecomings are rare for me and I’ve decided that when they come it’s stupid to reject them.

Now the central nervous system flipped to automatic, but also to a kind of insensate virtuosity (remember: a deaf, dumb and blind kid sure plays a mean pinball). Without will, my palms worked the flippers to keep balls in the game, and after losing one—shucks—my brain (left? right?) registered with satisfaction the next one’s self-reloading, a mechanical caddy getting me just what I needed when I needed it, and then the suspenseful exertion of pulling back the spring-loaded plunger against its non-negligible resistance, noting the partial unspooling of the spring, touched with rust, and then of course the release.

It is just within this fathom-long body, with its perception and intellect, that I declare that there is the cosmos, the origination of the cosmos, the cessation of the cosmos, and the path of practice leading to the cessation of the cosmos.

Over the last twenty-five years, the internet has doggedly modeled for us a strange but familiar truth. Our lives are both here—in our beating hearts, in our thick-skinned, small-boned feet, in our despised fat, our buzzing brains—and elsewhere, in a fathomless realm channeled through our phones that we can but dimly intuit.

The first thing you notice with non-digital games is all the disreputable excitement possible with mere mechanics and electricity.

A conference space free of natural light or breezes is the ideal non-place to feel neither the richness of our bodies, nor the kaleidoscope of the internet, but only the uneasy suspension that comes from being monotonously tweeting and texting while walking, soundless steps on carpet that mutes our heft and gait. Now, as my game heated up, my phone sat on the ledge of a radiator by the soda machine, using its amoral programming to case the joint for open WiFi, casting about for signals like a hophead, still warm from my excessive attention to it. Dancing attendance on my phone, while pretending it is dancing attendance on me, is a charade I need long breaks from. Today pinball was my interlude.

The Monopoly-branded playfield was fundamentally non-digital, though I should add that I didn’t dissect it. I wanted my analog illusion, from a game launched barely after the millennium’s turn. I was willing to repress all evidence of even electronics, so profoundly did I want reprieve from nonlinear signal processing.

The first thing you notice with non-digital games is all the disreputable excitement possible with mere mechanics and electricity. The pinball “interface,” such as it is, doesn’t screen you out from its greasier machine parts, the way Apple has taught us hardware must. Being closer to grease means being closer to the sordid and further from the embalmed interfaces made up as if by a mortician: Apple, Google, Facebook—further from, let’s say, the lies. Mechanics don’t lie. The madness of our living, dying, jamming, clogging time on earth is laid bare in a carburetor. Mechanics worked well on this pinball table because Monopoly, with its theme of greed, is not a wholesome story. There’s something in rusted springs and leering monopolists that belongs in the half-finished basement of a cathouse, as entertainment for the preteen sons of sex workers eager to forget the corruption around them without outright going to church.

Springs, plungers, tilt sensors, bumpers, holes. I played and played till my wrists ached. Every time a ball hit a bumper and the machine trilled with points, my person thrummed harder; if the ball ricocheted against the bumper and the points racked up—these sounds must have organic analogs in the blood vessels—I felt as if time stopped, I was for that throbbing instant immortal and, better yet, had no end of appetite for winning. Also, I was in the world and screened out. Things were in three dimensions and took up space. Non-LED light was produced by things big enough to make light: candle-sized, torch-sized. And balls hitting bells might have happened in the Middle Ages.

A harmonious experience is analog pinball—un-uncanny.

Check out the second part of “Tilt” here.

(Image credit: The Pinball Hall of Fame by Kent Kanouse on Flickr.)

The Product of Play: An Essay

Writer and game designer Kat Brewster looks into game playing as a constructive means in this first post of a two-part series.

In 1979, Sophie Calle returned to her native Paris after an extended period of traveling, and felt restless. “I felt completely lost in my own town,” she said. “I no longer knew how to occupy myself each day, so I decided that I would follow people in the street.”1 Calle reasoned that if she did not know what to do in Paris, other Parisians could show her. So, like a game of cat and mouse, she followed them. Just to see where they went. In this way, she says, “I let them decide what my day would be, since alone I could not decide.” When one of Calle’s subjects showed up at a party she attended that evening, she thought it was a sign. When he mentioned that he was traveling to Venice, she upped the ante. Calle’s following spiraled into an international chase as she, in a blond wig and trench coat, followed the man from Paris. She photographed Henri B., as she called him, for two weeks around the Italian city. When he finally confronted her, the game ended. The photographs Calle took and her accompanying diary became the artist’s first published work: Suite Venitienne.

“I did not consider myself to be an artist,” Calle later said of this phase in her life. “I was just trying to play, to avoid boredom.”

“Boredom,” as the German literary critic Walter Benjamin wrote in the notes for his unfinished Arcades project, “is the threshold to great deeds.” Play, like Calle’s, is often an activity born of restlessness, engaged with to alleviate a sense of stagnation. The Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johann Huizinga defined it in 1938 as “a free activity, standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as ‘not serious,’ but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it.”2 Huizinga’s eighty-year-old definition is a popular one, and has served well for a foundational understanding of the activity. Play is a process which exists separately from a player’s ordinary life, or the common denominator of their lived experience. It is also considered to be done purely for the sake of it without the hope of profit. It is for these reasons that the activity is frequently derided in Western capitalist societies, particularly in adults. “I was just playing,” one might say to extricate themselves from a social faux-pas. “Stop goofing around, be serious.” “This isn’t a game.” “Don’t play with me.” These phrases serve to reinforce a culture which devalues play.

Boredom is the threshold to great deeds.

When play is both not real and not for profit, its worth in a society reliant on a hierarchy of tangible production is precarious. The eight hour workday, established in large part in the 1880s, was intended to delineate productive labor from self-directed pursuits and rest. For the artist, however, that barrier between productive labor and creative labor—that which is typically expected to fill one’s leisure time—is a more permeable one. Indeed, it could be said that all artistic practice is a departure from typical labor, and in turn, deemed “not-serious.” Play and art both are often considered fruitless pastimes. In large part, the high-school graduate who tells their parents: “I want to be an artist,” strikes more fear than saying, “I want to be an economist.” That is, depending on the parents.

Children are granted an amnesty in playtime. Child psychologist D. W. Winnicott championed the child who plays as one who is rationalizing the boundaries of acceptable behavior, engaging in what he deemed “reality testing.”3 The same could be said of the radical artist, who shifts and renegotiates cultural boundaries and understanding. Whether simply for themselves, or through large-scale exhibitions, modern and contemporary art has been shaped by playful practice and deviating from an established ordinary. They elevate the activities relegated to simple leisure, often experimental and stimulating, to the status of “high art.”

Returning to Calle’s Suite Venitienne, with its focus on play and distraction, it is clear that hers was an intentional deviation from the monotony of her fraught Parisian life. She projected herself into a thrilling fiction, and where she previously felt directionless and lost, she now had purpose. “There were photos and notes,” Calle said. “Being in control, losing control, making up for emotional gaps, becoming attached to someone, if only for half an hour.”4 Play is the only activity where one may perform what one isn’t, to see what it is like. It is a safe space for self-exploration. Calle plays at being out of control through a strict set of rules, and creates a game.

Calle, of course, is not the only artist to have gotten their start in play, or in avoiding the mundane. Within the confines of the formal art world, perhaps the most celebrated deviation from an established ordinary is the Salon des Refusés. Following the rejection of an unprecedented 3,000-plus paintings to the 1863 Paris Salon—a juried show sponsored by the French government and the Academy of the Fine Arts—Napoleon III had their works exhibited in a parallel show. The exhibition was called the Salon des Refusés, or, The Salon of the Refused. Though Napoleon III perhaps had intended to solely balm the sting of refusal, he also succeeded in legitimizing a state-approved alternative to the academy. Suddenly, there was more than one way to achieve recognition, funding, and patronage. Those artists shown in the parallel show rejoiced in their relegation of refusal, and endured the initial ridicule which the exhibition incited, and eventually they would become one of the most celebrated groups in modern art: the Impressionists.

Check out part two of this essay—with the Impressionists and Dadaists at play—here.

1 Curiger, Sophie Calle in Conversation, 50.

2 Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 13.

3 Winnicott, Playing and Reality, 6.

4 Macel, Biographical Interview with Sophie Calle, 77.

(Image credits: Image © Sophie Calle, published by Siglio Press. “Palais de L’industrie, Paris Exposition, 1889,” Henry Clay Cochrane Collection at the Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections, Quantico, VA, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Dorothea Lasky on the PlayTime Manifesto

“Play is the step before the step before the thing that we decide is of value. It takes us so many tries, if at all, to realize the twirling around is the thing of worth.”

—Dorothea Lasky, poet and Astro Poet

Art for the Ages: An Image Gallery

While Grand Theft Auto and German Romanticism may seem diametrically opposed, artist Claire Hentschker describes how the desire to capture the sublime potential of nature through an idealized scene transcends the ages.

Rückenfigur, literally “back-figure” in German, is a compositional device that was often used by Caspar David Friedrich. In Friedrich’s painting Wanderer in the Sea of Fog, the viewer is invited into the composition through a figure in the painting’s foreground that serves as surrogate for the scene. We see the back of the man’s black coat as he stands atop a rocky terrain before the grandness of the sea, horizon, and sky before him. The man gazes into sublime nature, and through him—this Rückenfigur—we, the viewers of the painting, become immersed in the setting and can witness his grand view of the landscape with our own eyes, as if through the back of his head. Grand Theft Auto V presents a similar opportunity for immersion into a landscape by way of an avatar with its back turned—a digital Rückenfigur of sorts.

Owning and playing Grand Theft Auto (GTA) is not the only way to experience the majesty of a digital world that has been created to encapsulate the narrative of the game. Many individuals participate in the YouTube economy of posting and watching videos of gameplay. Such documentation videos are frequently recorded in third-person mode, characterized by the back of an avatar at the center of the screen through which the player navigates the world. With this perspective, the landscape shifts while the avatar remains relatively fixed in the foreground of the scene. Unlike in Friedrich’s world, the Rückenfigur through which we experience the GTA landscape is not necessarily human. There are third-person videos to be found featuring any or all the following protagonists: bikes, cars, trucks, trains, motorcycles, blimps, helicopters, boats, and even all-powerful and immortal deer. (The latter the result of a fantastic artwork by Brent Watanabe.)

The desire to capture the sublime potential of nature through an idealized scene may have begun with Friedrich, but it transcends the ages, as evidenced in the names of uploaded gameplay videos. Excerpts entitled GTA 5 Sunset, GTA V: Beautiful sunset flight, Grand Theft Auto V—The Drive Through The Sunset, GTA 5—Beat The Sunset: A Drifting Montage, only begin to scratch the surface of the vast amount of video recorded by one player’s avatar’s experience of the same algorithmic sunset. These videos consistently feature comments by viewers expressing their gratitude for the video and their shared appreciation of the beauty of the landscape. For example, viewer GTAgreat says, “Good job. Sunset is breathtaking :OOO.”

“I want to investigate Grand Theft Auto as a subject of art that transposes Caspar David Friedrich’s subjective Romanticism to the digital age.”

In this series of works, I want to investigate Grand Theft Auto as a subject of art that transposes Friedrich’s subjective Romanticism to the digital age. I am particularly interested in working with videos that other players have already deemed important enough to share. This collection provides a sampling of GTA’s digital world that incorporates both the gaze of an avatar and the eyes of a living viewer encoded into the experience of the scene. The view and the location presented around the avatar is a representation of what a single player decided to record and share.

To create the images in the series, I employed a technique called “image averaging,” notably used previously by artists such as Jim Campbell and Jason Salavon. The average of a series of digital images is calculated so that the more consistent characteristics shared by the images are rendered in greater detail. In this case, I was using video frames from YouTube videos of GTA gameplay. The game’s avatar, consistently encountering the world around it, remains a constant presence on the screen and is therefore rendered in more detail than the surrounding world. As the world passes by, the avatar remains virtually unchanged, and the contrast between the more realized avatar and the blur of the shifting landscape becomes evident in the resulting images. Each image is the sum of someone’s desire to share an imaginary world through a gameplay video. And, as Sammy R—in the comments section of one of these videos assures us—“This is Art.”

(Image credits: Images courtesy of the artist. Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer in the Sea of Fog, 1819, oil on canvas, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Kit That Fits: An Essay

In an era when women’s rights to equality are recognized, writer Anne Miltenburg asks, why do female athletes face such challenges finding gear that fits and performs well? This is the first installment of a two-part essay.

Over the past hundred years, the design of sports uniforms has been evolving at top speed. There was a day when soccer players wore rugged cotton crewnecks, woolen socks, and heavy cleats that weighed them down, and their shirts were devoid of sponsor logos. Today, they wear kit that is lighter and more breathable than ever, and sponsors pay big bucks to be seen on a team jersey. In fact, professional athletes playing for a sponsored team are contractually obligated to wear the sponsor’s uniforms and gear. These uniforms are designed down to the very structure of the fibers for maximum range of motion, minimum skin friction, and optimal body temperature. Boots have specially designed studs specifically configured for firm ground, soft ground, or artificial turf, ensuring faster turns, better kicks, and fewer injuries. Nor is there any end in sight to the improvements that are yet to be made.

Sports brands are in a race to design ever better gear to help athletes run faster, jump higher, swing harder, and look better while doing so. When it comes to the design of team sports uniforms for female athletes, however, it is often quite a different story. Karin Legemate, a retired Dutch professional soccer player, recalls her experiences with sports uniforms with a mixture of disappointment and wonder: “At AZ, a first division club, our sponsor was Quick, a sports brand that does not have a line for women. As a result, we had to play in the smallest men’s size and in kids’ shoes.” Because competitions are waged mentally as well as physically, Legemate experienced it as a huge impediment. “You stand on the field in a bag. It just looks wrong. It feels wrong. You are an athlete, you want to look like one. So mentally, you are already at 0:1.” Your standard of play goes down too. “The children’s shoes don’t have aluminum studs. When you are playing on grass, you can’t turn as well, you slip, you get injuries quicker, you have to hold yourself back.” It was not until she became a member of the Dutch national soccer team that she first experienced a great kit designed for women by the official sponsor, Nike.

According to Legemate, with the right gear you have more confidence, and it shows on the field. Without good gear, the game becomes less fun for the players and for the audience as well. “When women’s soccer has a small viewership, sponsors are less interested. Without sponsors, women athletes have to cover all their own costs. It’s already impossible to support yourself as a professional female soccer player. All of us have to combine it with normal jobs. If you have to pay for your own gear it is just another setback.”

For Muslim soccer players, this is just another difficulty in what is an already disappointing industry. Most sports brands originate in the West, and within the industry there are tremendous hesitations, misgivings, and dilemmas around designing sports clothing for Muslim women. Is designing sportswear with head coverings a way to enable these women to play sports, or does it play into the hands of those who suppress women’s rights? Princess Reema Bint Bandar Al Saud, Vice President of Women’s Affairs at the General Sports Authority, Saudi Arabia, found herself at the center of this dilemma when she had to make some quick decisions for the team of female athletes participating in the Rio Olympics in the summer of 2016. Because the decision to enter a women’s team—a first in the country’s history—was made quite late, the athletes were offered small sizes of the men’s uniforms that the national team sponsor had created, but even if they had received uniforms designed for women, Princess Reema doubts that they would have been suitable for her team. “The sponsoring brand does not yet design for women who cover their hair. In our culture, women cover themselves in public. Covered is also how we dress for formal occasions. The Olympics are a formal occasion.” Princess Reema wanted to both show the world that Saudi women could compete with the best, and show her country that sending women to the Olympics was a great idea, but in order to do so, she had to find a solution that would allow the women to perform at world-class levels while also being covered according to societal norms.

She turned to a high-street brand for off-the-rack burkinis and hijabs. “We have athletes competing in the marathon. They need to have a uniform that is as aerodynamic as possible and allows them to regulate their body temperature, but our athletes cannot wear a skin-tight body suit even if it covers the entire body and our hair. We need something that is modest and yet enables us to compete with others without being at a disadvantage.” It is a challenge waiting for the right sports brand or the right designer to take on.

[Khalida Popal] is quick to point out that the debate should not be about whether or not the sports hijab represents a restriction of women’s rights. The debate should be about allowing all women to participate, regardless of their religion or background.

Khalida Popal, former captain of the Afghan women’s national soccer team, joins Princess Reema Bin Bandar Al Saud with her passionate plea for sports brands to create solutions which allow Muslim women to participate in sports. She recently collaborated with Danish sports brand Hummel to create the official Afghan sports uniform, which includes a line for women, with or without hijab. She is quick to point out that the debate should not be about whether or not the sports hijab represents a restriction of women’s rights. The debate should be about allowing all women to participate, regardless of their religion or background. “Before we had the Hummel uniform it was very difficult for me, as a leader of the team, to find comfortable clothing that did not irritate or disturb the players. And it was so hot! With the built-in hijab we look professional, and it helps parents to give their consent for their daughters to play sports.”

Parents do not necessarily ask their daughters to wear a hijab because of their own religious beliefs. In places like Afghanistan there are those on the hunt for any woman who crosses the line of strict behavioral and clothing codes, and they inflict gruesome punishments on trespassers. Requiring girls to play in hijabs is often as much a sign of love and concern for their safety as it is a cultural or religious habit. In Popal’s words, “The uniform with the built-in hijab breaks barriers. It is a way to say: look, sport is not against religion. Sports and religion are not adversaries. We’ve received a very positive response from within Afghanistan.” Interestingly, most of the negative responses have come from people in the West who believe that the hijab curbs women’s rights, but Popal firmly disagrees. “You have to understand: it gives us opportunity. Now we can play. Without it we could not.”

Despite the fact that the national team now has its own uniform, for the aspiring amateur soccer player in the country, there are still no options. According to Popal, “No other companies have jumped in to create a uniform with hijab for the general market, unfortunately.”

While one side of the world is engaged in a discussion of how to cover up, the other is in a battle over whether or not to strip down. Some people consider the sex factor in women’s uniforms as key to improving the viewership of women’s sports. During an interview in 2004, Sep Blatter, then the head of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association, said: “Let the women play in more feminine clothes like they do with volleyball. They could, for example, have tighter shorts. Female players are pretty, if you’ll excuse me for saying so, and they already have some different rules to men, such as playing with a lighter ball. That decision was taken to create a more female aesthetic, so why not do it with fashion?” Sep Blatter is not alone, and women’s teams across the world have to live with the consequences.

Keep reading with the second installment of “Kit That Fits.”

(“Kit That Fits” originally appeared in Works That Work, No 9. Image credit: Latvia vs Russia Women’s Olympic Basketball – Beijing 2008 by kris krüg on Flickr.)

Cecilia Weckstrom on the PlayTime Manifesto

“Play connects hearts and reminds us of our humanity.”

—Cecilia Weckstrom, Global Head of Environmental Responsibility Engagement, LEGO

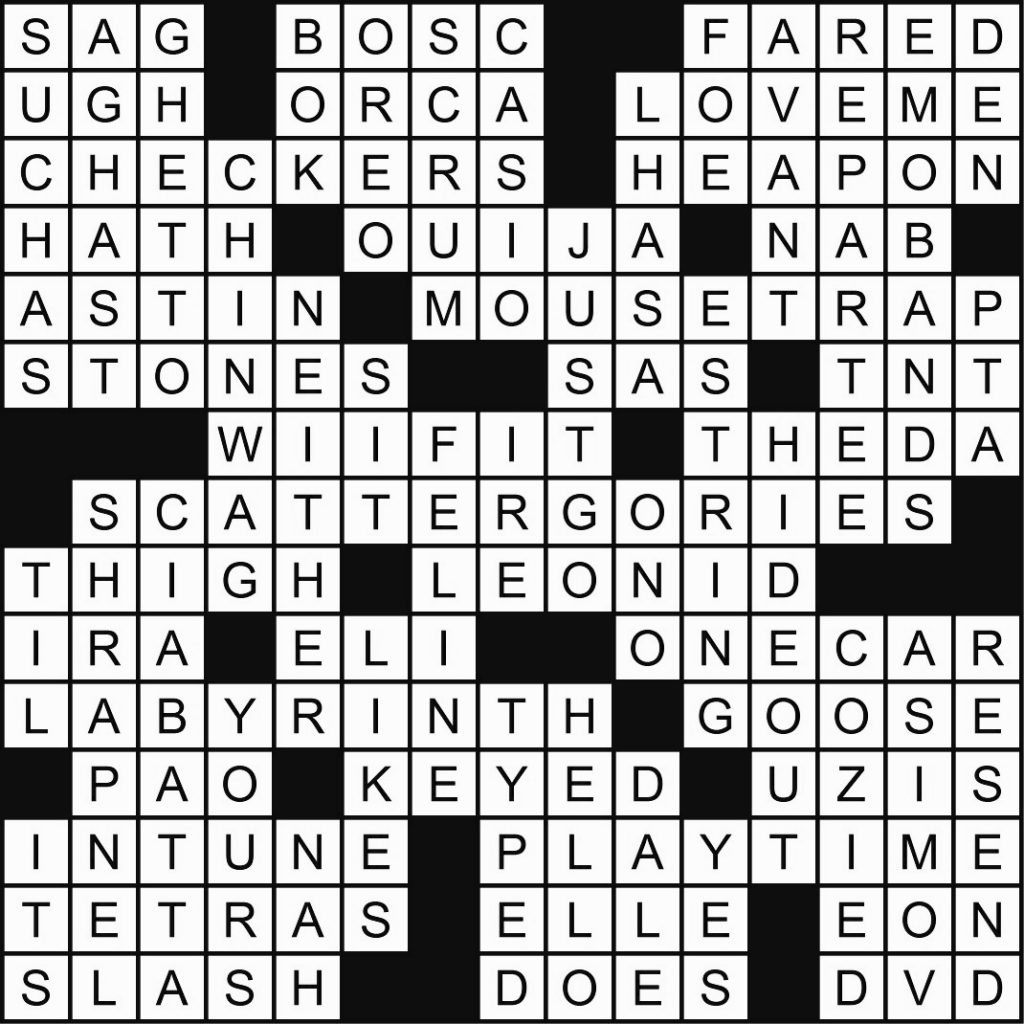

Game-Changing: Crossword Puzzle Solution

Note: Contains spoilers for the crossword puzzle, so please play first!

Play has been a major part of my life for as long as I can remember. Before I started constructing crossword puzzles, I played with everything from jigsaw puzzles to Hot Wheels cars. I especially loved word games like Scrabble, Super Scrabble, and Jotto, so my eventual crossword obsession wasn’t too much of a surprise! Now that I’m older, play plays (pun intended) a huge role in every crossword puzzle I make. Perhaps the best way to illustrate that is to walk you through how I constructed this puzzle.

My inspiration was actually a comic strip called Baby Blues, in which the two children in the strip’s regularly occurring family of characters have combined chess, Monopoly, Candy Land, Mousetrap, and other board games, as one of them exclaims, “How many Yahtzees does it take to sink a Battleship?”

This strip had me laughing out loud—what a preposterous mixture of board games! “Wait a second,” I remember thinking, “a mixture of board games … a puzzle I’m building for an exhibit about play … playing with board games for wacky results … classic rebus puzzles … maybe I’m onto something here!” My brainstorm started with the games in the comic. Queen Frostine is from Candy Land, so how about reparsing “Candy Land” as “c and yland,” forming the rebus clue “CYLAND”? Not a bad example, but also not a “Wow!” in my mind since so many of the letters (Y, L, A, N, and D) don’t get played with.

After a few more false starts (not much I could do with CHESS, and none of the ideas I had for MONOPOLY worked out to my satisfaction), I noticed Mousetrap. Aha, what about making a literal mousetrap? When I noticed I could clue MOUSETRAP as “Ope[rat]ion,” another board game, I was off and rolling.

One thing I really like about this idea is how each theme clue is a mini-puzzle of its own, thus focusing more heavily on play than a traditional crossword would. For those of you who are still puzzled, here’s a breakdown of the theme clues:

S

E = the letters E, R, and S in a checkmark = CHECKERS

R

Ope[rat]ion = a mouse trapped in a longer word = MOUSETRAP

Sergio = an anagram of the letters G, O, R, I, E, and S = scatter gories = SCATTERGORIES (Note: I also could have gone with the clue “Orgies,” but I didn’t want to play dirty ;).)

TLARH = the letters LA next to the letter R, all of that surrounded by the letters T and H = la by r in th = LABYRINTH

Once the theme was in place, I moved on to the fill. To me, filling a crossword puzzle is a form of group play: I want to make sure everyone is having a good time by sprinkling in liveliness (which I tried to do with entries like SHRAPNEL, CIABATTA, and CHINWAG), while at the same time keeping obscurity and uninteresting entries to a bare minimum. When I’m stuck using a weak entry, I once again focus on solvers. Nobody’s going to love PAO (clued as “Kung ___ chicken”) or BOK (“___ choy”), but on the plus side, these trade-offs are relatively easy fill-ins and give newer solvers toeholds. “Crosswordese” trade-offs like oast (a hops-drying oven) and amah (an Asian nanny) are to me the worst kinds of entries since they’re neither interesting nor inferable. I avoid such entries as much as possible, because they seem like foul play.

Some of my favorite pun/misdirection clues here are “Kind of board used for spelling” (OUIJA), “You might skip them” (STONES), “Glass on the radio” (IRA), “Pitch perfect?” (IN TUNE), “Leftmost member of a violin quartet?” (E STRING), and “They’re in the singular” for ITS. But it would get annoying and tiring if every clue were a pun. My philosophy on clues is to make them playful but not obtrusively so.

Happy solving!

Light on Stone: A Role-Playing Game

Light on Stone is a pervasive game, a game that extends a game’s rules from the written word into the real world. Game designer Anna Anthropy asks us to play along, and to question the nature of bodies vs. avatars and the value we find in non-productive time.

“It’s funny that you asked. The truth is, the real anna—the original—vanished long ago. No one knows for sure why, but I imagine she had grown very tired. It was decided, however, that the world needed an anna anthropy, and so the Tradition began. I am not the first to have taken up her mantle, nor will I be the last. Hers are big shoes to wear, but we do not take the responsibility lightly.”

The year XYZ. Humans are long extinct, but civilization lives on. A billion artificial minds float through the Light World, a boundless virtual palace of living information. Most know humanity only through the archives, of which all human history makes up the merest fraction. Few have visited the physical world, the Stone World, at all.

You are an AI grown in the waning days of humanity, and you remember the Stone World. Or perhaps you are one of the younger minds, only a few thousand years old, intensely curious about a world that that you have never seen but, in some almost cosmological way, nevertheless inhabit.

You have constructed a hull. There are fabrication devices in the Stone World that are still wired into the system. It was a long process, not for lack of data on how to rearrange matter, but because of the challenges of conceiving of what a body in that world would look like, would need. You had to imagine yourself into physical existence.

Your new body is frail but at the same time unexpectedly strong. Its every surface bristles with sensors, feeding you sensory details in an richness and detail that are at first overwhelming, even for you, who are made of data. Downloading yourself into the material world, you feel cold for the very first time.

The Stone World is mostly grey and hard now, but it is still there. There are patches of green. The wind blows through it. And there are, without a doubt, others like you, strangers in this broken place.

To play this game, imagine that you are an AI discovering the physical world for the first time. What does your hull look like? What demands does it make? What does it feel like to move in this body? What does the wind feel like on your face? How strange is it to have a body in the first place?

Old buildings, standing hollow. Transit systems, somehow still running. The rare patch of living earth. You have all the data there is to have on these things, except for what it means to experience them. Try and imagine what humans would have done in these spaces. How does it feel to move through them?

This world can be beautiful but is overwhelming to to dwell in for too long – too cold, too slow, too much. Fortunately, you can move between the Stone World and Light World at will. Whenever you look at a screen, like your phone, you have returned to the Light. Imagine your hull standing silent and still in the cold wind of a barren world.

Do you try and document your experiences for the Light? Not what Stone places are – there’s more than enough information archived on anything you might find. What there isn’t information on is what those things feel like. If you record your journeys, will anyone care? Or do you keep these experiences to yourself, like secrets?

Does the Light World still feel the same now that you’ve touched Stone? ♦

(Image credit: Grass in the Sidewalk by Eric on Flickr.)

Hunt the Slipper: A Story

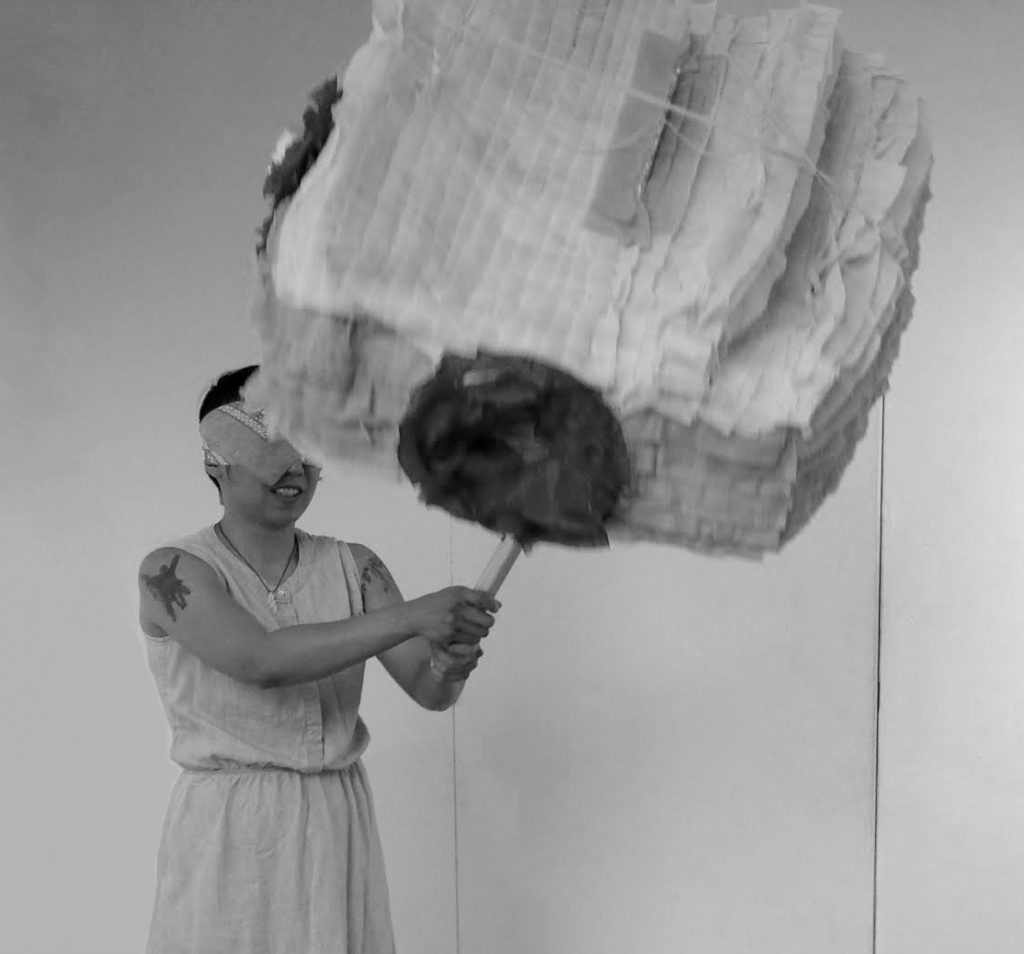

Albert Mobilio’s fictional stories are based on old-time games played in parlors, basements, and fields with balls, brooms, blindfolds, and cards. As winners and losers emerge from dodge ball, word games, and balloon contests so does the theme of our inner life as ceaseless competition. There is calculation, envy, humiliation, and joy, and there is always the next round when everything might change.

All players but Jack sit in a circle close together, with feet drawn up and knees raised so as to form a tunnel underneath the circle of bent knees. They pass a slipper from one to the other through the tunnel, trying to keep it hidden. Something about this ready-made tunnel strikes Sandy as unnerving—how easily a pocket of hiddenness can be made in plain sight. She laughs because everyone does yet stiffens in response to the newly made coolness below her bare legs, registering its kinship to caves, basements, and things unspoken.

The slipper isn’t glass or golden. Not one used for ballet or tightrope walking. An ordinary slipper. Torn seams, sole soiled from trips across the sidewalk to toss trash or the times it’s traveled all the way to the Bagel Delight on the corner. This slipper smells slightly of baby powder. Jack stands outside the circle and tries to follow the slipper’s covert passage and tag the player who has it. He doesn’t give a damn about the slipper or how he’ll be able to trade places with whoever he tags. What’s happening in his head is what he cares about: there seems to be a hockey puck sliding around the ice rink beneath the dome of his skull. Every movement—he bends down or charges forward—sends the disc caroming into the wall, the reverberation pulsing around his eyes. He can still taste the sweetish rum they were passing around, but not in his mouth—the taste rises up from his stomach. Where is that damn thing? The lights have been turned very low and he can’t even make out where people’s legs meet the floor let alone anything else. Better to follow the movements of shoulders than try to follow the slipper itself.

The bunched up thing comes Sandy’s way, the thin flannel cuff immediately familiar because the slipper is hers. She would have preferred not to use it—she might as well pass her socks around, too—but it’s her apartment and who else would have a slipper. Did Jess flinch the tiniest bit when it was in her hands? Sandy could swear she saw that. Could swear she saw a flicker of distaste. Jack darts this way and that, incorrectly tagging where he’s sure he discerned the telltale dip in Jess’ shoulder, then Frank’s friend, and that friend’s friend. He really needs to sit and let his headache have its way but just as he’s about to give up, he notices Sandy’s downcast eyes. She’s unaware, caught up in some faraway thought. He tags her, or really, because he has to lunge, he slaps her on the shoulder.

“You’ve got it,” he says. Without looking up, she offers the slipper. There’s the scent of baby powder. The inside worn smooth. He starts to put his hand inside as if it were a glove but he doesn’t. He shouldn’t. He knows that.

“Didn’t mean to hit you,” he says.

“That’s okay.” Sandy takes the slipper back. “Let’s hide something else.” ♦

(Image credit: Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.)

The Players

Anna Anthropy is game designer in residence at DePaul University. She is the author of Rise of the Video Game Zinesters, A Game Design Vocabulary (with Naomi Clark), and ZZT. Read more from Anna Anthropy.

Sarah Archer is a writer, critic, and curator. She is the author of Midcentury Christmas and she is a contributing editor for American Craft Inquiry, a contributor to Hyperallergic, and columnist for the Magazine Antiques online. Check out Sarah Archer’s piece.

Tedi Asher is the neuroscience researcher at the Peabody Essex Museum. A Harvard Medical School doctoral graduate, she is the first neuroscientist to join the staff of an art museum. At PEM, Asher helps to inform exhibition design strategy by analyzing emerging neuroscientific findings and proposing recommendations to increase engagement and visitor impact. Check out Tedi Asher’s piece on how play has the power to heal.

Chris Bachelder is the author of the novels Bear v. Shark, U.S.!, Abbott Awaits, and The Throwback Special, which was a finalist for the 2016 National Book Award for fiction. He is a frequent contributor to McSweeney’s and The Believer, and currently teaches creative writing at the University of Cincinnati. Check out Chris Bachelder’s story.

Nashra Balagamwala is an experiential designer whose work frequently transforms controversial and sensitive topics into unique games, designs, and experiences. Prior to working in New York and Pakistan, she attended the Rhode Island School of Design and worked at Hasbro Inc. Read more from Nashra Balagamwala.

Pippin Barr is an assistant professor in the Department of Design and Computation Arts and associate director of the Technoculture, Art and Games Lab at Concordia University, Montreal, Canada. A game designer, he is the author of How to Play a Video Game. Read more from Pippin Barr.

Eugenia Bell is the guest editor for playtime.pem.org. She is the former executive editor of Design Observer and Design Editor of Frieze. Her writing has appeared in Frieze, Artforum, Bookforum, and Garage, among other places. Check out our weekly Play Digest link pack each Friday for more from Eugenia Bell.

Adam Bessie is a writer whose cartoons and graphic journalism have been featured in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, and the Project Censored book series. Bessie is a professor of English at a San Francisco Bay area community college and the father of a kindergartener. His likeness is portrayed here by Marc Parenteau. Check out Adam Bessie and Jason Novak’s monthly comic, Board Gaming the System.

Kat Brewster is a writer and game designer whose work focuses on digital culture, specifically games. Brewster’s work has been featured in the Guardian and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Read Kat Brewster’s piece.

Rutherford Chang is an artist best known for his large-scale projects We Buy White Albums and Game Boy Tetris, an online exhibition in which he records himself playing Tetris over and over in an attempt to achieve the highest score ever recorded. His work aims to rearrange ordinary things to uncover the truths behind them. Watch Rutherford Chang compete for the top spot among Nintendo Game Boy Tetris players.

Tom Chatfield is an author, broadcaster, and commentator on digital culture and tech philosophy. A regular speaker on BBC radio and television, he is also the author of Live This Book!, How to Thrive in the Digital Age, and Fun Inc. Read Tom Chatfield’s piece.

Cole Cohen is the Brooklyn-based author of the memoir Head Case: My Brain and Other Wonders. Her previous work has appeared in Vogue and The Atlantic. Read Cole Cohen’s piece.

Katherine Cross is a doctoral student in sociology at the Graduate Center of The City University of New York. Cross is a widely published social critic whose work focuses on human-machine interactions, anti-social behaviour online, and the ways we engage with media. Check out Katherine Cross’s piece.

Natalie Diaz is a former professional basketball player turned poet and writer. Her debut collection of poetry is When My Brother Was an Aztec.

Adam Dixon designs and writes about games. His work explores communities, politics, civic tech, and entrepreneurship. Dixon has run workshops about games and game design at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Wellcome Collection, and NowPlayThis. Check out Adam Dixon’s piece.

Cara Ellison is a Scottish author and video game designer, though she started out making radio at BBC Radio 4. She has written for PC Gamer and The Guardian. Ellison’s book, Embed with Games, chronicles her travels around the world asking questions about why people make games and what they are for. Read Cara Ellison’s piece.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning novelist, journalist, and essayist. Editor of Best Canadian Sports Writing and author of the essay collection Baseball Life Advice, Fowles writes about books for The Globe and Mail, and baseball for Jays Nation and The Athletic. She lives in Toronto. Read Stacey May Fowles’s piece.

Jane Friedhoff is a game developer and creative technologist who loves designing games that encourage silly and absurd behaviors in public spaces. She co-founded the Code Liberation Foundation, which provides free, trans-inclusive, women-only game design and programming classes. Check out Jane Friedhoff’s game Lost Wage Rampage. Join us for the upcoming panel, Game Changers: Women Activists in Digital Space, with Angela Washko, Susana Morris, and Jane Friedhoff at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Tracy Fullerton is a game designer, educator and author. She is currently director of the joint University of Southern California Games Program, a collaboration between the School of Cinematic Arts and the Viterbi School of Engineering, and professor and chair of the Interactive Media & Games Division of the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts. Watch our interview with Tracy Fullerton.

Josh Gondelman is a writer and comedian who incubated in Boston before moving to New York City, where he currently lives and works as a writer for Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. He is also the co-author of the book You Blew It and co-founder of the Modern Seinfeld Twitter account. Check out Josh Gondelman and Molly Roth’s comic series Games Adults Play.

Lydia Gordon is an Assistant Curator for Exhibitions and Research at the Peabody Essex Museum. Prior to joining PEM, Gordon worked for the Society of Contemporary Art at the Art Institute of Chica go and as a Curatorial Fellow for the department of Exhibitions and Exhibitions Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Read more from Lydia Gordon. Gordon will be moderating the upcoming panel Game Changers: Women Activists in the Digital Space, at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Frank Guan, music columnist at Vulture, is interested in the experience and economics of video games. His work has been published in New York Magazine, The New Republic, and n+1. Guan is also a poet and the founding editor of the poetry magazine Prelude. Read more from Frank Guan.

Charlie Hall is a senior reporter for Polygon, a leading games website. His work covers games and the people who make them. He specializes in embedded reporting, uncovering narratives inside obscure communities. His work includes a history of interaction with U.S. military and intelligence agencies. Check out Charlie Hall’s piece.

Matthea Harvey is professor of poetry at Sarah Lawrence College. She has written five books of poetry, including If the Tabloids Are True What Are You? and Modern Life, as well as two children’s books, Cecil the Pet Glacier and The Little General and the Giant Snowflake. Check out Matthea Harvey’s piece.

Owen Hatherley writes regularly on aesthetics and politics for the Architectural Review, The Calvert Journal, Dezeen, the Guardian, Jacobin, the London Review of Books, and New Humanist, among other publications. He is the author of several books, most recently Landscapes of Communism, The Ministry of Nostalgia, and The Chaplin Machine. Read Owen Hatherley’s piece.

Virginia Heffernan is a journalist, author, and cultural critic. She is currently a contributing editor at Politico, co-host of Trumpcast on Slate, and a columnist at Fast Company. Previously, she wrote “The Medium,” a column on internet culture for The New York Times Magazine. Her most recent book is Magic and Loss: The Internet as Art. Read Virginia Heffernan’s piece.

Claire Hentschker is an artist and current graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University. She is interested in site specific mixed reality, and her virtual reality work has been shown at the Carnegie Museum of Art, VIA Festival, and the Free State Festival. Check out Claire Hentschker’s work.

Martin Herbert is a writer and critic based in Berlin. His critical writing appears regularly in Artforum, Frieze, Art Monthly, and ArtReview, where he is associate editor. He is the author of Mark Wallinger, The Uncertainty Principle, and Tell Them I Said No. He lectures regularly in international art schools and is on the jury for the 2017 Turner Prize. Read Martin Herbert’s piece on artist’s work and working in the studio.

Juliana Horner is a designer, illustrator, and makeup artist living in New York City. She has been called “Instagram’s wildest makeup star” by Vogue. Check out the first of Juliana Horner’s three-part makeup series.

Sarrita Hunn is an interdisciplinary artist whose often collaborative practice focuses on the culturally, socially, and politically transformative potential of artist-centered activity. She is co-founder/editor of Temporary Art Review and the art editor for Exberliner, an English language print magazine in Berlin, Germany. Play Inter/de-pend-ence here.

Julia Jacquette is an American artist based in New York City and Amsterdam. Her work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the RISD Museum, among other institutions. Jacquette’s work was recently the subject of a retrospective at the Tang Museum in Saratoga Springs, New York. She is currently on the faculty at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York. Read Julia Jacquette’s piece.

Marisa Morán Jahn is an artist, multimedia designer, educator, and the founder of Studio REV-, a nonprofit organization that leads public art projects and tools to impact the lives of low-wage workers, immigrants, women, and youth. Learn more about Marisa Morán Jahn‘s work with PEM and Horizons for Homeless Children.

Melissa Kaseman is a photographer based in Seattle, Washington. Her work has been exhibited in group shows in Portland, Oregon; San Francisco; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Santa Fe, New Mexico. She was an artist in residence at Minot State University in her hometown of Minot, North Dakota. Check out Melissa Kaseman’s photographs.

Andrew Kuo is a New York–based artist, who has held solo shows at Marlborough Chelsea, Galleria Marabini, and Artists Space, among others. Check out the start of our series of infographics from Andrew Kuo.

Travis Larchuk is the head writer for NPR’s trivia, puzzle, and word play show Ask Me Another. Watch our interview with Travis Larchuk.

Javier Laspiur is a photographer based in Madrid, Spain. He is a senior art director at Comunica +A. Check out Javier Laspiur’s photographic series Consolas.

Mike Lazer-Walker makes interactive art, experimental games, and software tools. His work has been featured at IndieCade, the Game Developer’s Conference, the Smithsonian Museum and on NPR’s All Things Considered. Most of his work focuses on reframing everyday objects and spaces as playful experiences with nontraditional interaction models. Until recently, he worked with the MIT Media Lab’s Playful Systems research group. Read more from Mike Lazer-Walker.

J. Robert Lennon is the author of two story collections, Pieces For The Left Hand and See You in Paradise, and eight novels, including Mailman, Familiar, and Broken River. He teaches writing at Cornell University. Click through for J. Robert Lennon’s story game.

Colleen Macklin is a game designer, and associate professor of media design and co-director of Prototyping, Evaluation, Teaching and Learning Lab (PETLab), a public interest game design and research lab for interactive media, at Parsons School of Design. Her work has been shown at the Come Out and Play Festival, SoundLab, the Whitney Museum for American Art, and Creative Time. Watch our interview with Colleen Macklin.

Anne Miltenburg is a designer based in Nairobi, Kenya. An inveterate traveler, she has lived and worked across Europe, and in Mali, South Korea, Australia, and the U.S. Miltenburg is the founder of The Brandling. Read more from Anne Miltenburg.

Albert Mobilio is the author of several poetry collections and a fiction collection, Games and Stunts. Mobilio is an assistant professor of literary studies at the New School, an editor at Hyperallergic Weekend, and contributing editor at Bookforum. Check out the first story in our series from Albert Mobilio.

Anis Mojgani is a two-time National Poetry Slam Champion and winner of the International World Cup Poetry Slam. He is the author of five books. His latest is In the Pockets of Small Gods.

Susana Morris is a blogger, activist, and associate professor in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Institute of Technology. As co-founder of the Crunk Feminist Collective, she is committed to illuminating women’s stories and experiences. She is the author of Close Kin and Distant Relatives: The Paradox of Respectability in Black Women’s Literature. Read more from Susana Morris. Join us for the upcoming panel, Game Changers: Women Activists in Digital Space, with Angela Washko, Susana Morris, and Jane Friedhoff at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Sianne Ngai is professor of English at the University of Chicago specializing in American literature, literary and cultural theory, and feminist studies. She is the author of Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting and Ugly Feelings. Check out more from Sianne Ngai.

Jason Novak is a cartoonist. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Rumpus, and Harper’s Weekly, and more. Check out Adam Bessie and Jason Novak’s monthly comic, Board Gaming the System.

Sergio Pellis is a professor of animal behavior and neuroscience at the University of Lethbridge in Canada. A central focus of his research is on the evolution, development and neurobiology of play behavior. Read more from Sergio Pellis.

Alexander Perrin is an illustrator, technical artist, and game developer based in Melbourne, Australia. Perrin aims to create engaging, intuitive, and welcoming experiences that appeal to a wide range of players, including those who do not typically identify with the video game world. He is currently working alongside artist Josh Tatangelo at 2pt Design Studios to create considerate games and interactive media. Check out Alexander Perrin’s game A Short Trip.

Walker Pickering is a photographer and transmedia artist. A native Texan, he teaches photography, video, and bookmaking at the University of Nebraska. His work has been exhibited throughout the United States and internationally, and is included in a number of private and public collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and The Wittliff Collection of Southwestern & Mexican Photography. Take a look at Walker Pickering’s photographic series Esprit de Corps.

Artist Pedro Reyes lives and works in Mexico City. He has won international attention for large-scale projects that address current social and political issues. His varied practice utilizes sculpture, performance, video, and activism. Watch our interview with Pedro Reyes.

Randall Roberts is a Los Angeles-based writer and journalist who covers music culture for the The Los Angeles Times. His work can be found online at ballparkvillage.com. Read more from Randall Roberts.

Carlo Rotella is a professor of English at Boston College. His book Cut Time: An Education at the Fights was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Rotella’s work has also appeared in numerous publications, including the New York Times Magazine, Boston Globe, The New Yorker, Chicago Tribune, Harper’s Magazine, and The Believer. Check out Carlo Rotella’s work.

Molly Roth is a Michigan-born, Brooklyn-based graphic artist and humorist. She works on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker Daily Shouts, McSweeney’s, and Vox. Check out Josh Gondelman and Molly Roth’s comic series Games Adults Play.

Karen Russell is a renowned fiction writer and the author of Swamplandia!, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, Vampires in the Lemon Grove: Stories, and Sleep Donation: A Novella. Read Karen Russell’s thoughts on writing and play.

Naomi Russo is an Australian writer who generally covers design, art, and the environment. Her work has been published in the Atlantic and Australian Geographic. Read more from Naomi Russo.

Tamara Shopsin is a graphic designer and illustrator whose work is regularly featured in The New York Times and The New Yorker. She is the author of two memoirs, Mumbai New York Scranton and Arbitrary Stupid Goal. She is also designer of the 5 Year Diary, co-author with Jason Fulford of the photobook for children, This Equals That, and a cook at her family’s restaurant in New York City. Check out Tamara Shopsin’s piece.

Gwen Smith is a photographer living and working in New York. She describes herself as “an artist, a mother, a seeker, a finder, and a player.” Watch our interview with Gwen Smith.

Trevor Smith is Curator of the Present Tense at the Peabody Essex Museum and curator of PlayTime. He leads PEM’s Present Tense initiative, which celebrates the central role that creative expression plays in shaping our world today. Why PlayTime? Trevor Smith tells us more about the film that inspired the exhibition and its title.

Lizzie Stark is the author of Pandora’s DNA, which explores the history and science of the so-called ‘breast cancer genes,’ and Leaving Mundania, which investigates the subculture of live action roleplay, or LARP. Her journalism and essays have appeared in the Washington Post, Daily Beast, io9, Fusion, and Philadelphia Inquirer. Check out Lizzie Stark’s piece.

David Steinberg is a crossword puzzle constructor and editor. At fourteen, he became one of the youngest persons to ever publish a crossword puzzle with The New York Times, and has since authored two books of puzzles, Chromatics and Juicy Crosswords. Steinberg also founded the Pre-Shortzian Puzzle Project, a collaborative effort to build a digitized, fully analyzable database of New York Times crossword puzzles. David Steinberg’s custom PlayTime crossword can be found here.

Stanley Thangaraj is a socio-cultural anthropologist with interests in race, gender, sexuality, class, and ethnicity in Asian America in particular and in immigrant America in general. He is an assistant professor in the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership at the City College of New York. He is a former high school and collegiate athlete and coach who considers sport a key site to understand immigrant enculturation, racialization, and cultural citizenship. Read more from Stanley Thangaraj.

Photographer B.A. Van Sise’s work has been featured on the cover of The New York Times, in the pages of Newsday and the Washington Post, and on PBS NewsHour and NPR. A number of his portraits of notable American poets are in the collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Check out B.A. Van Sise’s photographs for PlayTime.

Tom Vanderbilt is a contributing editor of Wired (UK), Outside, and Artforum. He is the author of Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What It Says About Us), You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice, and Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America. Check out Tom Vanderbilt on foosball.

Rob Walker is a columnist for The New York Times Sunday Business section, and he contributes to many other publications, writing about design, technology, business, and the arts. His most recent book, co-edited with Joshua Glenn, is Significant Objects: 100 Extraordinary Stories About Ordinary Things. Walker and Glenn also oversee PROJECT:OBJECT, an ongoing series of personal stories about material possessions. Read more from Rob Walker.

Angela Washko is an artist, writer, and facilitator devoted to creating new forums for discussions of feminism in the spaces most hostile toward it. She is a visiting assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University. Since 2012, Washko has also been facilitating The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft. Watch our interview with Angela Washko. Join us for the upcoming panel, Game Changers: Women Activists in Digital Space, with Angela Washko, Susana Morris, and Jane Friedhoff at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Boris Willis is Chief Artistic Officer of Boris Willis Moves and Associate Professor of Computer Game Design at George Mason University. Watch our interview with Boris Willis.

Christine Wong Yap is a New York–based artist. Her work has been exhibited in the San Francisco Bay area, as well as in New York, Los Angeles, Manila, Manchester, and more. Her work has been supported by the Queens Council on the Arts, the Jerome Foundation, and the Center for Cultural Innovation. Play Inter/de-pend-ence here.

Eric Zimmerman is a game designer and co-founder of the game studio Gamelab, game design collective Local No. 12, and The Institute of Play. He is a founding faculty and arts professor at the New York University Game Center in the Tisch School of the Arts. His book, Rules of Play (with Katie Salen), was published in 2003. Watch our interview with Eric Zimmerman.