Tag: pem-playtime

Tilt: An Essay

In the second installment of her two-part essay, writer Virginia Heffernan continues her pinball pilgrimage and humanizes the digital-analog divide. Missed part 1? Read it here.

There were also beeps in this game. When my balls—my extra balls by now, I’m that good—hit one particular bumper and bounced back on it, again and again, piling up points and aiming me for the leaderboard, the beeps beeped furiously. Each one was a half-second, more or less tonal, and—as usual for me—beeps sit on the knife’s edge of puzzling and rapturous.

Beeps belong to nature and electricity and electronics and the Internet. All the centuries. Like the railroad toot but unlike an old telephone ring, beeps have both a distinct start and finish, marked by the twin plosives “b” and “p,” and an elastic center that can generously expand and contract like an accordion: beeeeeeeep. You can create Morse code in beeps. Beeeep beep beep beep. Beep. Beep. Beep beeeep beeeep beep. Yes, they’re a frankensound—but nature can almost, almost suggest them. They certainly seem to have always existed. Maybe art teases beeps out of nature.

The beep is synthetic; it’s manmade, like climate change. Plants don’t beep, nor weather, nor animals, nor birds except Road Runner. If you hear a beep, you know that a person, or more likely his artifact, is signaling. There’s no wondering, Is that a beep or a nightingale? Is that a beep or a tornado? Beeps are also not voices or music.

And still, sonically exotic as they may be, beeps are, as my pinball home insistently suggested, easy to make; they are cheap and light. No wonder everything beeps. E-mail beeps. Texts. Trucks in reverse. Hospital monitors. Stoves, dashboards, cameras, clocks. Coffee machines. Dishwashers. Elevators. Toys. Robots. Toy robots.

[In] the Monopoly game the beeps were modulated and engineered to define my experience, the very victories I thought I was creating with my analog tendons and fingertips and wrists.

The onomatopoeic word “beep” launched in 1929, and prewar beeps were produced by car horns, though sonar, electric elevators, and clown horns may have beeped or protobeeped even before the 1920s. Other car horns of the period, and now especially those of big cars, are usually heard to “honk.” Beeps as the sound of cute cars—makes sense. A small, zippy, nuisancey thing chirping, “’Scuse me, could you move a smidge? Thanks!” That’s a beep.

As a source for beeps, car horns gave way to piezoelectric technology, a breakthrough used increasingly after World War II in labs, hospitals, and military operations. With the arrival of the transistor, small piezo buzzers could be made to beep in devices like electronic metronomes and game-show buzzers. An efficient, low-power way to gin up a tone for a device to emit. Beeps could now be heard in a range of contexts, but the sound still managed to speak of seriousness and technology.

The material world and our bodies, in concert, can reconfigure themselves, as if to prove they can’t be digitized.

Were those beeps on the pinball playfield digitized? I choose to believe they were not made in sound labs, but date from the bells and horns of J.P. Morgan days. That every time a ball hit a bumper it squeaked because it was weighted metal on hard, smooth rubber, and something in the angle—and I misread it as a beep—but I’m not crazy: Naturally on the Monopoly game the beeps were modulated and engineered to define my experience, the very victories I thought I was creating with my analog tendons and fingertips and wrists.

Beautifully, submissively, we have adjusted to the hegemony of computers. But this Monopoly table, with its rusty screws and peeled paint, suggests one road back or through to an ecstatic, three-dimensional, and entirely mortal form of culture, in which our imperfect and limited bodies might reassert their centrality to culture, politics, and philosophy. This reassertion I anticipate with some giddiness the way, in my Bolshevik days, I used to anticipate the digital revolution. This time I resolve not to be so impatient with my elders.

The material world and our bodies, in concert, can yet reconfigure themselves, as if to prove they can’t be digitized. I believe that. In games like this one, from 2001, before broadband razed our nervous systems, I hear trills of promise. Of course, on this day, I was at forty-five in the middle of the journey my life, lost in the dark wood of an executive hotel. I was a truant; I had skipped a conference for a stolen pinball game. And reader: I was winning. ♦

(Image credit: Pinball by el-toro on Flickr.)

Kit That Fits: An Essay

Writer Anne Miltenburg examines the controversial and ever-changing world of women’s sportswear in a two-part essay. Here, we resume her discussion of the lack of proper professional gear for women. Check out part 1 here.

Why don’t female soccer players amp up the sex appeal to increase enthusiasm for women’s sports? “If sports was only about long legs, then women’s beach volleyball would be the biggest sport in the world,” remarks Shammy Jacob, former Director of Sustainable Ventures at Nike. “Of course performance should come first. Only then is it about looking great as an athlete. But looking great does not equal looking sexy.” To prove her point, Jacob offers an historic example. In the 1990s, Nike had been working with the American women’s national soccer team to design their outfits for the upcoming world championships. One of the things the women asked for was a better bra, one designed for sports. “To all of our amazement, Brandi Chastain scores the winning goal of the tournament, and celebrates by sliding onto her knees and taking her shirt off, revealing her sports bra.” The moment was captured in a photo that made the cover of Sports Illustrated and became a landmark image in the history of women’s sports. Jacob rejects the idea that the image was iconic because it was revealing. “What the shot showed was an athlete at the top of her game. To have everyone see a woman so fit, so strong, so victorious, and to receive so much attention, that made a world of difference for women’s sports at that time. Nike focused on performance but made sure the styling was also relevant and tasteful.”

Of course performance should come first. Only then is it about looking great as an athlete.

Despite the fact that more women are playing and watching sports, and that general viewership for women’s sports is increasing, women’s sports uniforms in most parts of the world remain stuck in a vicious circle. Without evidence of demand, sports brands won’t invest in creating professional gear for women. Without high-quality gear, fewer women play and fewer still play at their best, making games less exciting for spectators and less interesting for sponsors and sports brands, closing the circle of low demand.

One brand that is looking to break the circle is Liona, a new sports brand from the Netherlands, founded by former professional soccer player Leonne Stentler. Seeing that no brand was taking up the challenge of providing high-quality gear for women, Stentler decided to jump into the gaping hole in the market. Launched in 2015, Liona is already supplying professional league teams across the country with uniforms. Growing up as a child playing and during her entire professional career, Stentler took the absence of women’s kit as a given. “There is no women’s clothing available all the way to the top of the league. It is a huge investment for brands to produce a “second line” for women . . . . It is a men’s game; we are not a priority.”

The better the professional gear, the better the player. The better the player, the bigger the audience. With bigger audiences comes more sponsorship, allowing more women to have a career in sports.

Together with a fashion designer, Stentler started to redesign women’s uniforms. Most innovations came naturally to Stentler, who had seen firsthand what was needed. “All girls wear tights underneath their shorts for when they make slides. So our Liona shorts have built-in tights. Their waistbands are wider for more comfort. Shirts are longer than those for men and wider at the hips.” The response to Liona has been overwhelmingly positive. Luckily, it is not just praise that is rolling in, but orders as well. Liona has just supplied FC Twente with its women’s team uniform and the team is raving. “This is what is needed in the long run to create more confidence, to attract sponsors, and to lift the sport to a higher level,” says Stentler.

Stentler is not alone in seeing massive opportunities for women’s sports uniforms. With the availability of great sports gear, the vicious circle female athletes have found themselves in can become an upward spiral: the better the professional gear, the better the player. The better the player, the bigger the audience. With bigger audiences comes more sponsorship, allowing more women to have a career in sports.

Princess Reema Bint Bandar Al Saud, Vice President of Women’s Affairs at the General Sports Authority, Saudi Arabia, is one of the players looking forward to joining Stentler’s cause while focusing on the needs of Muslim women. “The market is not just girls in the Middle East. There is a pan-Islamic diaspora. Imagine a young girl in Birmingham who wants to compete. Why would you exclude her from the game?” Anne Skovrider of Hummel agrees. At the end of the day, access to the sport is what it should be all about: “Let these girls go out, play, get fit, learn teamwork, get confidence, feel good about themselves. That is what we want to support.” ♦

Return to the first installment of “Kit That Fits.”

Photo credit: Khalida Popal, former captain of the Afghan national women’s soccer team. Courtesy of Hummel.

What’s your take on the MANIFESTO? Tell us: PLAY is ____________. #PEMplaytime

Play Digest: LEGO Edition

Play Digest is our weekly link pack of themed recommended reading — items we enjoyed or found interesting and hope our readers will too. LEGO, everyone’s favorite Danish building toy, has been in the news lately.

It came as a surprise last month when the company announced a major round of layoffs, but this week came the happier news of a “women of NASA” set that will feature astronomer Nancy Grace Roman, computer scientist Margaret Hamilton, and astronauts Sally Ride and Mae Jemison. LEGO’s philosophy—that learning through play promotes innovation and creativity—is no longer groundbreaking, but its product continues to be fodder for researchers, scientists, and psychologists who have tapped the potential of the toy to illustrate the nimbleness of the human mind.

LEGO is serious play for many psychologists. Researchers are looking at the act of building with LEGO—and the results—as conceptual spaces to learn about play psychology and how to apply it to teaching the psychology of creativity itself.

Maybe some people spend too much time on LEGO: “It is clear that our participants treated LEGO people differently than LEGO nonpeople.”

Academics are looking at the rigidity of LEGO kits and are advocating for the right to “un-make.”

Related: does following the instructions make people less creative? Perhaps. Here are some people who go off-piste with their LEGO building:

Designer Milan Madge built a huge Leica camera in his free time.

Architects at Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) have completed an institutional project for LEGO in the company’s home-base of Billund, Denmark: the 12,000-square-foot Lego House.

In 2015, Olafur Eliasson hosted The Collectivity Project on New York’s Highline, a massive collective build that used only white bricks.

Japanese children reimagined their country in 1.8 million bricks during the “Build Up Japan” event in 2012.

Ai Wei Wei both addressed a political controversy in LEGO form, while LEGO courted some in its response to the project. This project, Trace, is currently on view at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC.

Check in next week for a new roundup of the latest play news and stories.

(Image credit: Ai Wei Wei’s Trace installed at Alcatraz prison in 2014 courtesy of Glen Bowman via Flickr.)

Spycraft: An Essay

Journalist Charlie Hall offers a look into the art of making board games for the CIA. Acclaimed designer Volko Ruhnke shares a whole new meaning to the term “serious games” with him.

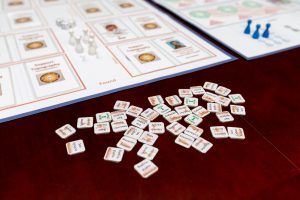

The United States intelligence community has a long history with gaming. Role-playing and simulations have been part of the Central Intelligence Agency’s best practices for generations, and are often conducted with the help of judges and mediators behind closed doors to explore complex, real-world situations.

But recently, the CIA revealed that they also use tabletop games—in effect, complex modern board games—to train its own analysts, and analysts from other agencies.

By day, Volko Ruhnke is an instructor at the CIA’s Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis. By night, Ruhnke is an acclaimed designer of commercial board games best known for the COIN Series, published by GMT Games. He said the CIA has been interested in tabletop games for a very long time, well before he started working there in the 1980s. Applying his knowhow in the commercial space to building games for CIA officers in a classroom setting was a natural fit. The goal, he explained, is to facilitate repetition in the practical application of intelligence gathering skills, about separating actionable information from noise and acting on it quickly.

Unlike commercial board games, Ruhnke’s projects at the CIA don’t need to be fun.

Ruhnke shared an example of his work, a project called Kingpin: The Hunt for El Chapo, which he co-designed with another instructor in the Defense Intelligence Agency. Kingpin uses the historical details of the capture of Sinaloa drug cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán as well as some fictional elements to create a challenging, asymmetrical game.

Kingpin is an adversarial game where one side plays the role of law enforcement and the other plays the role of Guzmán’s own handlers and associates. It revolves around hidden information, with each side playing on their own hidden game board behind a screen. El Chapo’s team is constantly moving around inside Mexico trying to evade the law, but the cartel leader has certain tastes and expectations. He’s not just willing to sit inside a hole somewhere, and one viable strategy is for law enforcement to use his proclivities against him. In the classroom, the game is played twice, with students taking turns playing on both sides of the table.

The key to the game, and to every other game played at the Kent School, is the facilitator. It’s their responsibility to keep things moving by interpreting the rules and feeding them to students on the fly. But in Kingpin, the facilitator also plays the role of referee. They have an important role in moving the action forward by revealing new information to both sides.

Unlike commercial board games, Ruhnke’s projects at the CIA don’t need to be fun. They also don’t need to support multiple playthroughs. In fact, they don’t even need to be played to completion.

“For a training game, it’s not nearly as important that you finish the game,” Ruhnke said. “It’s not even important that the game be balanced or have replay value. It might have those things. But our students are probably never going to play it again. It’s more about the insights and the process.”

Games are a very small fraction of what Kent School students will do in their coursework, but Ruhnke said the kind of hands-on work that tabletop gaming provides is invaluable.

Humans deal with complexity by forming mental models. . . . as instructors, we have to communicate those models to our students. Games do that very well.

“They are a tremendous tool for helping us prepare our understanding of complex affairs,” Ruhnke said. He likened it to studying the ongoing instability in Iraq and Afghanistan. “An insurgency is the interactions of many different actors, interests, tribes, forces, political movements, parties, village elders. It’s a complex compilation of factors, and that’s what we’re asking our analysts to understand. But human beings deal with complexity by forming mental models. So now, as instructors, we have to communicate those models to our students. Games do that very well.”

I was first introduced to the Ruhnke’s design work with a game called Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001 – ?, first published in 2010. In it, one player takes on the role of the United States while the other plays as Islamic jihadists. Each player takes actions by playing from a hand of cards that includes real-world, historical events. In one of my most memorable playthroughs the US prevailed only by keeping Benazir Bhutto alive long enough to drive the opposing player entirely out of Pakistan.

I asked Ruhnke about the potential conflicts that might arise between his commercial work and his classified work at the CIA.

“It is something that I have to watch,” he said. “I use my judgement in choosing to participate in work that’s outside of CIA work, and I’m not alone in that,” Ruhnke said. “I have . . . authorities here to double check. And in situation where I could have been exposed to sensitive information, I need to make sure that I’m okay here. That’s a routine procedure at the CIA. In my case, it happens to be that I’m making games, but if I were writing a book or writing an editorial in a newspaper it would be the same thing.”

The most gratifying part of the job for Ruhnke is in bringing intelligence officers together in a low-pressure environment in the same room with their peers. The Kent School isn’t just for members of the CIA, but provides instruction for analysts from the sixteen members of the United States Intelligence Community and all branches of the armed forces.

“It’s professionals coming together to practice their craft,” Ruhnke said, “separated from the immediate, pressing needs of our country. Of course, they’re interacting with each other every day, but in here it’s coming off the line, getting together as a brotherhood or a sisterhood of terrorism analysts. . . . I think it has to help.” ♦

(Image credit: Detail from Kingpin, a board game used by the CIA based on the capture of Mexican drug kingpin Joaquín Guzmán, popularly known as El Chapo. All images courtesy Central Intelligence Agency.)

Board Gaming the System: A Comic Series

In this month’s comic, Jason Novak and Adam Bessie turn the classic board game Chutes and Ladders into a play obstacle course. The children surmount the walls and fences, and the barriers are transformed.

As fathers of young children, Jason and Adam have spent many fun hours playing board games, several of which were created by Parker Brothers, which made its start as a game company right in Salem, Massachusetts. These board games aren’t just about diverting play, but about rules you must follow to win. The rules of game often reflect the idealized rules and mores of the culture—by playing the game, you are learning how to behave in the culture. And thus, board games are like a time capsule, a way of seeing the dominant values of a place and time. Our five-part series, Board Gaming the System, honors the legacy of the board game (and the many hours we’ve spent playing them) and reimagines classic boards to reveal the unwritten rules of our culture today.

Come back for next month’s installment in the series.

The Trouble with Losing at Chess: An Essay

In the second installment of his essay, Tom Chatfield asks, does being human mean being conditioned to losing? Miss the first installment? Read it here.

To talk about machine fooling humans isn’t quite accurate, of course. If we are deceived, it is because other people have built machines intended to deceive us. If we endorse an illusion, it is because we have fooled ourselves into seeing it as truth. And if, eventually, Turing’s test is passed, the supposed divide between illusion and truth collapses—leaving us with the question of whether we call ourselves magic or mechanism. As they begin to replicate more and more human achievements, will our creations reveal our minds to be reproducible in software? Will they gesture beyond us to new kinds of mind—to a world in which we must abandon old conceptions of self?

For a vision of the second of these possibilities, you need look no further than the contemporary cult of the Singularity. Named after the event horizon surrounding the quantum singularity of a black hole—that threshold beyond which not even light can escape—the term was first used by author Vernor Vinge in the 1980s to describe how self-improving artificial intelligence might accelerate beyond humans, past a historical point of no return.

The Singularity offers a strange inversion of Turing’s game: a point at which time and technology dissolve into miracles. Two entities are at play. One is a shadow, a simulacrum, trying to convince its master to treat it as an equal. In the world of the Singularity, humanity is the shadow—trying to show its superiors that it still deserves some measure of consideration. After the Singularity, all old rules cease to apply.

I don’t believe the Singularity is coming, but I do take seriously its vision of technological apotheosis, not least because it draws upon the same fascination that Kempelen’s illusion harnessed: a vision of the future conditioned by games in which there are winners and losers, skill is measured on a single scale, and computation is synonymous with intellect.

What does it mean to play a computer at a game like chess? These days, it means losing. In 1997, humanity’s greatest chess champion, Gary Kasparov, was beaten before the eyes of the watching world by IBM’s Deep Blue. In 2016, Google’s AlphaGo did the same for Go champion Lee Seedol, besting humanity at a game orders of magnitude more complex than chess. In early 2017, an AI called Libratus vanquished the world’s best players at no-limit Texas Hold ‘Em, a game of bluff and imperfect information that some had hoped would remain dominated by humans.

How can we hope for anything other than obsolescence?

This progression points to a fundamental divide between people and machines. Much like athletes pushing up against the boundaries of biology, the increments of human improvement have hard limits. We advance towards a certain threshold in slowing steps. Across rapid generations of software and hardware, meanwhile, machines advance faster and faster. Since 1997, the world’s best human chess players have got perhaps a little better, helped by computers. Meanwhile, the speed at which Deep Blue calculated—around 11.4 gigaflops—has fallen more than an order of magnitude behind the 275 gigaflops powering Samsung’s Galaxy S8 smartphone, a device you can fit in your pocket. Modern supercomputers are many thousands of times faster than those built in 1997, and this trend as yet shows no sign of stopping. The Deep Blue of 1997 would stand about as much chance against today’s supercomputers as a two-year-old would against Kasparov.

Singularity theorist Ray Kurzweil coined the phrase “the second half of the chessboard” to help people conceptualize the staggering properties of this increase. The phrase refers to a mathematical parable, in which a scholar is told by a king that he can name any price as his reward for performing a great service. What I wish for, the scholar replies, is that you place one grain of wheat upon the first square of a chessboard, two upon the second, four upon the third, eight upon the fourth, and so on, until the chessboard is covered.

The king protests that this is too small a prize, but the scholar demurs. By the end of the first row of eight squares, he has 255 grains of wheat. By the time the first half of the chessboard is covered, he has 4,294,967,295 grains—around 280 tons. After this, the first square on the second half of the chessboard will contain as much wheat as the entire first half, and so on, until the wheat required becomes hundreds of times more than exists in the whole world. Once you reach a certain threshold, Kurzweil explains, any ongoing exponential increase demolishes old frames of reference: its sheer scale brings wholly new phenomena, and demands new ways of thinking.

By picking games like chess, humans have defined a terrain in which they are not only destined to lose but are also the architects of their own irrelevance.

How can we hope for anything other than obsolescence in the face of this exponential curve, lashing itself towards infinity? Within the bounds of game-worlds like chess and Go, the Singularity has come and gone. Never again in history will the world’s greatest player be an unaided human. Yet the game is not what it seems. By picking games like chess as both emblems of our rivalry and the ultimate arenas for training machine minds, humans have defined a terrain in which they are not only destined to eventually lose, but are also the architects of their own irrelevance—the creators of rule-bounded spaces within which any suitably-defined victory can be won by automation. Beyond this realm, however, the question of supremacy is not even the right one to ask.

Behind accounts of our near future such as Kurzweil’s lies a way of thinking called technological determinism. Determinism offers an account of the world in which the old is driven out by the new, sometimes violently, via mechanisms that nobody needs to have chosen. In warfare, guns beat spears—and people who choose to keep on fighting with spears will sooner or later find themselves on the wrong side of history. In business, advanced autonomous systems beat old-fashioned labour—and corporations who sentimentally refuse to replace their workforce with robots will sooner or later find themselves overtaken. Determinism’s logic is one of ceaseless winner-takes-all games between old and new—a context within which humanity itself is easily viewed as yesterday’s news.

Is this true? Evolution certainly requires no intentions in order to unfold. Yet inevitability, I would argue, exists only in retrospect—in a pattern that our minds project onto the world. We see a Turk seated at a chessboard, and so we also see intent and elemental opposition—a struggle for supremacy complete with winners and losers, old and new. Yet, while a machine may today beat us at chess, it is not actually playing in any recognizable human sense. Somewhere inside its circuits, human players remain hidden—programmers, designers, past grandmasters, creators of a history that has been uncomprehendingly digested and optimized. Our loss is also our victory. The only rules and measures we can lose by are those we have ourselves created.

What isn’t captured by such metrics? As the philosopher Bernard Suits put it in his 1978 book The Grasshopper, a game can also be thought of as “the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” We may play a game such as chess in the hope of winning. But this doesn’t make winning its purpose, any more than the purpose of listening to a symphony is getting to the end as fast as possible. Rather, the possibility of victory (and of losing, and of drawing) exists in order to create meaningful play: the exercise of skill and tactics, a pursuit undertaken for its own satisfaction. Constraint create the possibility of play, but it does not constrain the experiences play enables.

As strange it may seem to say it, this is also true of warfare, economics, and the other arenas in which we compete on a daily basis. Victory is the means to ends—power and influence, wealth and glory—that cannot remain meaningful if victory is the only value that matters. Economic rivalry may mean outdoing your rivals, but it also demands common aspirations if there is to be any economy worth succeeding within. The exponential logic of victory after victory does not hold for the human world—not when constraint and common ground are the places that any ultimate purpose resides. It’s our confusion of purpose with conquest, not any inherent property of machines, that’s most likely to destroy us.

Our loss is also our victory. The only rules and measures we can lose by are those we have ourselves created.

In his 1986 book Finite and Infinite Games, the religious scholar James Carse makes the case that “finite” games played for the purpose of winning are secondary to “infinite” games, played for the purpose of continuing further play. In Carse’s account, finite games are preoccupied by the kind of conflicts that determinism puts at the heart of history: power clashes in which faster, harder, bigger and better tools perpetually supplant weaker ones. Infinite games, however, take an interest in the process of play itself—and are alive above all to the possibility of surprises, transforming the trajectory of all that has come before. “To be prepared against surprise is to be trained,” writes Carse, “To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.”

How should we think about the games we play with and through our tools? The philosopher of technology Luciano Floridi uses a very different parable to that of the chessboard to describe our interactions with technology. Imagine a relationship, he writes in his book The Fourth Revolution, in which one partner is accommodating and adaptable, and the other is extraordinarily inflexible. Over time, if the relationship persists and neither partner’s personality changes, they will end up doing more and more things in the way that the less flexible partner insists upon—because their choice is either to do things this way, or not do them at all.

Even the most adaptable machine is orders of magnitude more inflexible than the most rigid human. Once design decisions have been made—once the boundaries of the game together with its incentives have been defined—our creations will be able to maximize its outcomes with ever-greater efficiency. The question is not whether this automatically makes us redundant, but rather whether we have meaningfully debated which incentives we do and do not wish to see relentlessly pursued on our behalf—a debate that can only exist between humans, and that has significance only in our interplay.

Few people learn chess because they wish to be the best in the world; fewer still because they wish to bring the history of chess-playing to a close. Play and learning are themselves the point—the spaces within which value resides. Similarly, when it come to humanity and history, neither our velocity nor our theoretical destination are the metrics that matter most. In constraint, in life and the playing of games, what counts is the experiences we create—and the possibilities we leave behind. ♦

(Image credit: Courtesy of Eureka Entertainment via Flickr.)

Our Aesthetic Categories: An Interview

Aesthetics as a philosophical discipline was an invention of the Enlightenment, and appropriately enough, most of the historical discussion has focused on the beautiful and the sublime. However, as J. L. Austin noted in “A Plea for Excuses,” the classic problems are not always the best site for fieldwork in aesthetics: “If only we could forget for a while about the beautiful and get down instead to the dainty and the dumpy.” Cultural theorist and literary critic Sianne Ngai has dedicated years of research to such marginal categories within aesthetics. She talks with Adam Jasper of Cabinet about her ideas.

Adam Jasper: You’ve written on cuteness, on envy, on boredom, and now on the interesting. If it could be said that there is a unified project behind these topics, what is it?

Sianne Ngai: I’m interested in states of weakness: in “minor” or non-cathartic feelings that index situations of suspended agency; in trivial aesthetic categories grounded in ambivalent or even explicitly contradictory feelings. More specifically, I’m interested in the surprising power these weak affects and aesthetic categories seem to have, in why they’ve become so paradoxically central to late capitalist culture. The book I’m currently completing is on the contemporary significance of three aesthetic categories in particular: the cute, the interesting, and the zany.

I focus on aesthetic experiences grounded in equivocal affects. In fact, the aesthetic categories that interest me most are ones grounded on feelings that explicitly clash. To call something cute, in vivid contrast to, say, beautiful, or disgusting, is to leave it ambiguous whether one even regards it positively or negatively. Yet who would deny that cuteness is an aesthetic, if not the dominant aesthetic of consumer society?

AJ: Can you say more about the qualities of non-cathartic feelings? The explicit rejection of catharsis was central to Brechtian theater, but is that what you are referring to here?

SN: By non-cathartic I just mean feelings that do not facilitate action, that do not lead to or culminate in some kind of purgation or release—irritation, for example, as opposed to anger. These feelings are therefore politically ambiguous, but good for diagnosing states of suspended agency, due in part to their diffusiveness and/or lack of definite objects.

AJ: To get our hands a little dirtier here, could you provide some examples of typically cute and typically zany things and indicate the characteristics that make them that way?

SN: Cuteness is a way of aestheticizing powerlessness. It hinges on a sentimental attitude toward the diminutive and/or weak, which is why cute objects—formally simple or noncomplex, and deeply associated with the infantile, the feminine, and the unthreatening—get even cuter when perceived as injured or disabled. So there’s a sadistic side to this tender emotion, as people like Daniel Harris have noted. The prototypically cute object is the child’s toy or stuffed animal.

Cuteness is also a commodity aesthetic, with close ties to the pleasures of domesticity and easy consumption. As Walter Benjamin put it: “If the soul of the commodity which Marx occasionally mentions in jest existed, it would be the most empathetic ever encountered in the realm of souls, for it would have to see in everyone the buyer in whose hand and house it wants to nestle.” Cuteness could also be thought of as a kind of pastoral or romance, in that it indexes the paradoxical complexity of our desire for a simpler relation to our commodities, one that tries in a utopian fashion to recover their qualitative dimension as use.

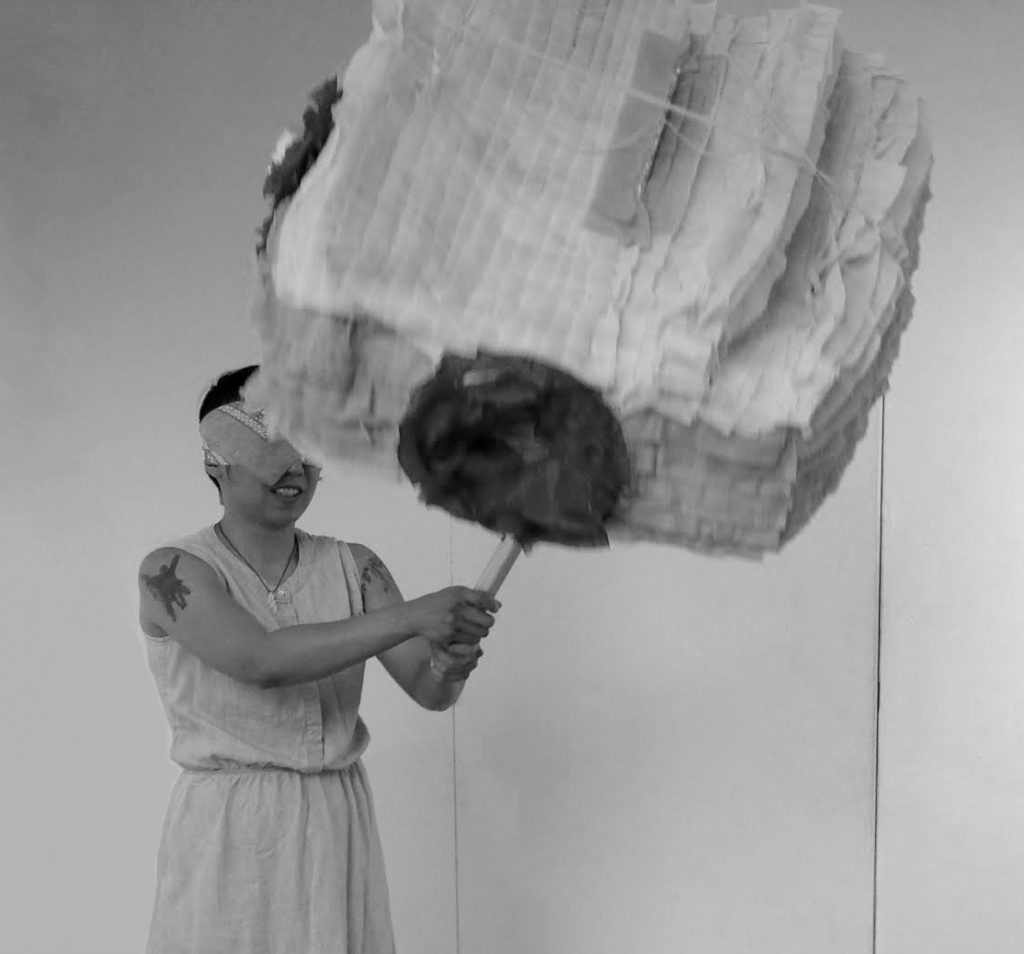

While the cute is thus about commodities and consumption, the zany is about performing. Intensely affective and highly physical, it’s an aesthetic of nonstop action that bridges popular and avant-garde practice across a wide range of media: from the Dada cabaret of Hugo Ball to the sitcom of Lucille Ball. You could say that zaniness is essentially the experience of an agent confronted by—even endangered by—too many things coming at her quickly and at once. Think here of Frogger, Kaboom!, or Pressure Cooker, early Atari 2600 video games in which avatars have to dodge oncoming cars, catch falling bombs, and meet incoming hamburger orders at increasing speeds. Or virtually any Thomas Pynchon novel, bombarding protagonist and reader with hundreds of informational bits which may or may not add up to a conspiracy.

The dynamics of this aesthetic of incessant doing are thus perhaps best studied in the arts of live and recorded performance—dance, happenings, walkabouts, reenactments, game shows, video games. Yet zaniness is by no means exclusive to the performing arts. So much of “serious” postwar American literature is zany, for instance, that one reviewer’s description of Donald Barthelme’s Snow White—“a staccato burst of verbal star shells, pinwheel phrases, [and] cherry bombs of . . . . puns and wordplays”—seems applicable to the bulk of the post-1945 canon, from [John] Ashbery to Flarf; Ishmael Reed to Shelley Jackson.

I’ve got a more specific reading of post-Fordist or contemporary zaniness, which is that it is an aesthetic explicitly about the politically ambiguous convergence of cultural and occupational performance, or playing and laboring, under what Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello call the new “connexionist” spirit of capitalism. As perhaps exemplified best by the maniacal frivolity of the characters played by Ball in I Love Lucy, Richard Pryor in The Toy, and Jim Carrey in The Cable Guy, the zany more specifically evokes the performance of affective labor—the production of affects and relationships—as it comes to increasingly trouble the very distinction between work and play. This explains why this ludic aesthetic has a noticeably unfun or stressed-out layer to it. Contemporary zaniness is not just an aesthetic about play but about work, and also about precarity, which is why the threat of injury is always hovering about it. ♦

(This interview between Adam Jasper and Sianne Ngai was originally published in Cabinet magazine, issue 43, 2011. Image courtesy Janeen via Flickr.)

Manifesto

PLAY spurs productivity.

PLAY is a catalyst for creativity.

PLAY is an escape from conformity.

PLAY reinvents the rules.

PLAY empowers the players.

PLAY stimulates innovation.

PLAY enables exploration.

PLAY is a response to uncertainty.

PLAY rewards misbehavior.

PLAY negotiates conflict.

PLAY resists productivity.

PLAY is _______________.

What’s your take on the MANIFESTO?

#PEMplaytime

Kit That Fits: An Essay

In an era when women’s rights to equality are recognized, writer Anne Miltenburg asks, why do female athletes face such challenges finding gear that fits and performs well? This is the first installment of a two-part essay.

Over the past hundred years, the design of sports uniforms has been evolving at top speed. There was a day when soccer players wore rugged cotton crewnecks, woolen socks, and heavy cleats that weighed them down, and their shirts were devoid of sponsor logos. Today, they wear kit that is lighter and more breathable than ever, and sponsors pay big bucks to be seen on a team jersey. In fact, professional athletes playing for a sponsored team are contractually obligated to wear the sponsor’s uniforms and gear. These uniforms are designed down to the very structure of the fibers for maximum range of motion, minimum skin friction, and optimal body temperature. Boots have specially designed studs specifically configured for firm ground, soft ground, or artificial turf, ensuring faster turns, better kicks, and fewer injuries. Nor is there any end in sight to the improvements that are yet to be made.

Sports brands are in a race to design ever better gear to help athletes run faster, jump higher, swing harder, and look better while doing so. When it comes to the design of team sports uniforms for female athletes, however, it is often quite a different story. Karin Legemate, a retired Dutch professional soccer player, recalls her experiences with sports uniforms with a mixture of disappointment and wonder: “At AZ, a first division club, our sponsor was Quick, a sports brand that does not have a line for women. As a result, we had to play in the smallest men’s size and in kids’ shoes.” Because competitions are waged mentally as well as physically, Legemate experienced it as a huge impediment. “You stand on the field in a bag. It just looks wrong. It feels wrong. You are an athlete, you want to look like one. So mentally, you are already at 0:1.” Your standard of play goes down too. “The children’s shoes don’t have aluminum studs. When you are playing on grass, you can’t turn as well, you slip, you get injuries quicker, you have to hold yourself back.” It was not until she became a member of the Dutch national soccer team that she first experienced a great kit designed for women by the official sponsor, Nike.

According to Legemate, with the right gear you have more confidence, and it shows on the field. Without good gear, the game becomes less fun for the players and for the audience as well. “When women’s soccer has a small viewership, sponsors are less interested. Without sponsors, women athletes have to cover all their own costs. It’s already impossible to support yourself as a professional female soccer player. All of us have to combine it with normal jobs. If you have to pay for your own gear it is just another setback.”

For Muslim soccer players, this is just another difficulty in what is an already disappointing industry. Most sports brands originate in the West, and within the industry there are tremendous hesitations, misgivings, and dilemmas around designing sports clothing for Muslim women. Is designing sportswear with head coverings a way to enable these women to play sports, or does it play into the hands of those who suppress women’s rights? Princess Reema Bint Bandar Al Saud, Vice President of Women’s Affairs at the General Sports Authority, Saudi Arabia, found herself at the center of this dilemma when she had to make some quick decisions for the team of female athletes participating in the Rio Olympics in the summer of 2016. Because the decision to enter a women’s team—a first in the country’s history—was made quite late, the athletes were offered small sizes of the men’s uniforms that the national team sponsor had created, but even if they had received uniforms designed for women, Princess Reema doubts that they would have been suitable for her team. “The sponsoring brand does not yet design for women who cover their hair. In our culture, women cover themselves in public. Covered is also how we dress for formal occasions. The Olympics are a formal occasion.” Princess Reema wanted to both show the world that Saudi women could compete with the best, and show her country that sending women to the Olympics was a great idea, but in order to do so, she had to find a solution that would allow the women to perform at world-class levels while also being covered according to societal norms.

She turned to a high-street brand for off-the-rack burkinis and hijabs. “We have athletes competing in the marathon. They need to have a uniform that is as aerodynamic as possible and allows them to regulate their body temperature, but our athletes cannot wear a skin-tight body suit even if it covers the entire body and our hair. We need something that is modest and yet enables us to compete with others without being at a disadvantage.” It is a challenge waiting for the right sports brand or the right designer to take on.

[Khalida Popal] is quick to point out that the debate should not be about whether or not the sports hijab represents a restriction of women’s rights. The debate should be about allowing all women to participate, regardless of their religion or background.

Khalida Popal, former captain of the Afghan women’s national soccer team, joins Princess Reema Bin Bandar Al Saud with her passionate plea for sports brands to create solutions which allow Muslim women to participate in sports. She recently collaborated with Danish sports brand Hummel to create the official Afghan sports uniform, which includes a line for women, with or without hijab. She is quick to point out that the debate should not be about whether or not the sports hijab represents a restriction of women’s rights. The debate should be about allowing all women to participate, regardless of their religion or background. “Before we had the Hummel uniform it was very difficult for me, as a leader of the team, to find comfortable clothing that did not irritate or disturb the players. And it was so hot! With the built-in hijab we look professional, and it helps parents to give their consent for their daughters to play sports.”

Parents do not necessarily ask their daughters to wear a hijab because of their own religious beliefs. In places like Afghanistan there are those on the hunt for any woman who crosses the line of strict behavioral and clothing codes, and they inflict gruesome punishments on trespassers. Requiring girls to play in hijabs is often as much a sign of love and concern for their safety as it is a cultural or religious habit. In Popal’s words, “The uniform with the built-in hijab breaks barriers. It is a way to say: look, sport is not against religion. Sports and religion are not adversaries. We’ve received a very positive response from within Afghanistan.” Interestingly, most of the negative responses have come from people in the West who believe that the hijab curbs women’s rights, but Popal firmly disagrees. “You have to understand: it gives us opportunity. Now we can play. Without it we could not.”

Despite the fact that the national team now has its own uniform, for the aspiring amateur soccer player in the country, there are still no options. According to Popal, “No other companies have jumped in to create a uniform with hijab for the general market, unfortunately.”

While one side of the world is engaged in a discussion of how to cover up, the other is in a battle over whether or not to strip down. Some people consider the sex factor in women’s uniforms as key to improving the viewership of women’s sports. During an interview in 2004, Sep Blatter, then the head of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association, said: “Let the women play in more feminine clothes like they do with volleyball. They could, for example, have tighter shorts. Female players are pretty, if you’ll excuse me for saying so, and they already have some different rules to men, such as playing with a lighter ball. That decision was taken to create a more female aesthetic, so why not do it with fashion?” Sep Blatter is not alone, and women’s teams across the world have to live with the consequences.

Keep reading with the second installment of “Kit That Fits.”

(“Kit That Fits” originally appeared in Works That Work, No 9. Image credit: Latvia vs Russia Women’s Olympic Basketball – Beijing 2008 by kris krüg on Flickr.)

The Players

Anna Anthropy is game designer in residence at DePaul University. She is the author of Rise of the Video Game Zinesters, A Game Design Vocabulary (with Naomi Clark), and ZZT. Read more from Anna Anthropy.

Sarah Archer is a writer, critic, and curator. She is the author of Midcentury Christmas and she is a contributing editor for American Craft Inquiry, a contributor to Hyperallergic, and columnist for the Magazine Antiques online. Check out Sarah Archer’s piece.

Tedi Asher is the neuroscience researcher at the Peabody Essex Museum. A Harvard Medical School doctoral graduate, she is the first neuroscientist to join the staff of an art museum. At PEM, Asher helps to inform exhibition design strategy by analyzing emerging neuroscientific findings and proposing recommendations to increase engagement and visitor impact. Check out Tedi Asher’s piece on how play has the power to heal.

Chris Bachelder is the author of the novels Bear v. Shark, U.S.!, Abbott Awaits, and The Throwback Special, which was a finalist for the 2016 National Book Award for fiction. He is a frequent contributor to McSweeney’s and The Believer, and currently teaches creative writing at the University of Cincinnati. Check out Chris Bachelder’s story.

Nashra Balagamwala is an experiential designer whose work frequently transforms controversial and sensitive topics into unique games, designs, and experiences. Prior to working in New York and Pakistan, she attended the Rhode Island School of Design and worked at Hasbro Inc. Read more from Nashra Balagamwala.

Pippin Barr is an assistant professor in the Department of Design and Computation Arts and associate director of the Technoculture, Art and Games Lab at Concordia University, Montreal, Canada. A game designer, he is the author of How to Play a Video Game. Read more from Pippin Barr.

Eugenia Bell is the guest editor for playtime.pem.org. She is the former executive editor of Design Observer and Design Editor of Frieze. Her writing has appeared in Frieze, Artforum, Bookforum, and Garage, among other places. Check out our weekly Play Digest link pack each Friday for more from Eugenia Bell.

Adam Bessie is a writer whose cartoons and graphic journalism have been featured in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, and the Project Censored book series. Bessie is a professor of English at a San Francisco Bay area community college and the father of a kindergartener. His likeness is portrayed here by Marc Parenteau. Check out Adam Bessie and Jason Novak’s monthly comic, Board Gaming the System.

Kat Brewster is a writer and game designer whose work focuses on digital culture, specifically games. Brewster’s work has been featured in the Guardian and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Read Kat Brewster’s piece.

Rutherford Chang is an artist best known for his large-scale projects We Buy White Albums and Game Boy Tetris, an online exhibition in which he records himself playing Tetris over and over in an attempt to achieve the highest score ever recorded. His work aims to rearrange ordinary things to uncover the truths behind them. Watch Rutherford Chang compete for the top spot among Nintendo Game Boy Tetris players.

Tom Chatfield is an author, broadcaster, and commentator on digital culture and tech philosophy. A regular speaker on BBC radio and television, he is also the author of Live This Book!, How to Thrive in the Digital Age, and Fun Inc. Read Tom Chatfield’s piece.

Cole Cohen is the Brooklyn-based author of the memoir Head Case: My Brain and Other Wonders. Her previous work has appeared in Vogue and The Atlantic. Read Cole Cohen’s piece.

Katherine Cross is a doctoral student in sociology at the Graduate Center of The City University of New York. Cross is a widely published social critic whose work focuses on human-machine interactions, anti-social behaviour online, and the ways we engage with media. Check out Katherine Cross’s piece.

Natalie Diaz is a former professional basketball player turned poet and writer. Her debut collection of poetry is When My Brother Was an Aztec.

Adam Dixon designs and writes about games. His work explores communities, politics, civic tech, and entrepreneurship. Dixon has run workshops about games and game design at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Wellcome Collection, and NowPlayThis. Check out Adam Dixon’s piece.

Cara Ellison is a Scottish author and video game designer, though she started out making radio at BBC Radio 4. She has written for PC Gamer and The Guardian. Ellison’s book, Embed with Games, chronicles her travels around the world asking questions about why people make games and what they are for. Read Cara Ellison’s piece.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning novelist, journalist, and essayist. Editor of Best Canadian Sports Writing and author of the essay collection Baseball Life Advice, Fowles writes about books for The Globe and Mail, and baseball for Jays Nation and The Athletic. She lives in Toronto. Read Stacey May Fowles’s piece.

Jane Friedhoff is a game developer and creative technologist who loves designing games that encourage silly and absurd behaviors in public spaces. She co-founded the Code Liberation Foundation, which provides free, trans-inclusive, women-only game design and programming classes. Check out Jane Friedhoff’s game Lost Wage Rampage. Join us for the upcoming panel, Game Changers: Women Activists in Digital Space, with Angela Washko, Susana Morris, and Jane Friedhoff at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Tracy Fullerton is a game designer, educator and author. She is currently director of the joint University of Southern California Games Program, a collaboration between the School of Cinematic Arts and the Viterbi School of Engineering, and professor and chair of the Interactive Media & Games Division of the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts. Watch our interview with Tracy Fullerton.

Josh Gondelman is a writer and comedian who incubated in Boston before moving to New York City, where he currently lives and works as a writer for Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. He is also the co-author of the book You Blew It and co-founder of the Modern Seinfeld Twitter account. Check out Josh Gondelman and Molly Roth’s comic series Games Adults Play.

Lydia Gordon is an Assistant Curator for Exhibitions and Research at the Peabody Essex Museum. Prior to joining PEM, Gordon worked for the Society of Contemporary Art at the Art Institute of Chica go and as a Curatorial Fellow for the department of Exhibitions and Exhibitions Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Read more from Lydia Gordon. Gordon will be moderating the upcoming panel Game Changers: Women Activists in the Digital Space, at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Frank Guan, music columnist at Vulture, is interested in the experience and economics of video games. His work has been published in New York Magazine, The New Republic, and n+1. Guan is also a poet and the founding editor of the poetry magazine Prelude. Read more from Frank Guan.

Charlie Hall is a senior reporter for Polygon, a leading games website. His work covers games and the people who make them. He specializes in embedded reporting, uncovering narratives inside obscure communities. His work includes a history of interaction with U.S. military and intelligence agencies. Check out Charlie Hall’s piece.

Matthea Harvey is professor of poetry at Sarah Lawrence College. She has written five books of poetry, including If the Tabloids Are True What Are You? and Modern Life, as well as two children’s books, Cecil the Pet Glacier and The Little General and the Giant Snowflake. Check out Matthea Harvey’s piece.

Owen Hatherley writes regularly on aesthetics and politics for the Architectural Review, The Calvert Journal, Dezeen, the Guardian, Jacobin, the London Review of Books, and New Humanist, among other publications. He is the author of several books, most recently Landscapes of Communism, The Ministry of Nostalgia, and The Chaplin Machine. Read Owen Hatherley’s piece.

Virginia Heffernan is a journalist, author, and cultural critic. She is currently a contributing editor at Politico, co-host of Trumpcast on Slate, and a columnist at Fast Company. Previously, she wrote “The Medium,” a column on internet culture for The New York Times Magazine. Her most recent book is Magic and Loss: The Internet as Art. Read Virginia Heffernan’s piece.

Claire Hentschker is an artist and current graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University. She is interested in site specific mixed reality, and her virtual reality work has been shown at the Carnegie Museum of Art, VIA Festival, and the Free State Festival. Check out Claire Hentschker’s work.

Martin Herbert is a writer and critic based in Berlin. His critical writing appears regularly in Artforum, Frieze, Art Monthly, and ArtReview, where he is associate editor. He is the author of Mark Wallinger, The Uncertainty Principle, and Tell Them I Said No. He lectures regularly in international art schools and is on the jury for the 2017 Turner Prize. Read Martin Herbert’s piece on artist’s work and working in the studio.

Juliana Horner is a designer, illustrator, and makeup artist living in New York City. She has been called “Instagram’s wildest makeup star” by Vogue. Check out the first of Juliana Horner’s three-part makeup series.

Sarrita Hunn is an interdisciplinary artist whose often collaborative practice focuses on the culturally, socially, and politically transformative potential of artist-centered activity. She is co-founder/editor of Temporary Art Review and the art editor for Exberliner, an English language print magazine in Berlin, Germany. Play Inter/de-pend-ence here.

Julia Jacquette is an American artist based in New York City and Amsterdam. Her work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the RISD Museum, among other institutions. Jacquette’s work was recently the subject of a retrospective at the Tang Museum in Saratoga Springs, New York. She is currently on the faculty at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York. Read Julia Jacquette’s piece.

Marisa Morán Jahn is an artist, multimedia designer, educator, and the founder of Studio REV-, a nonprofit organization that leads public art projects and tools to impact the lives of low-wage workers, immigrants, women, and youth. Learn more about Marisa Morán Jahn‘s work with PEM and Horizons for Homeless Children.

Melissa Kaseman is a photographer based in Seattle, Washington. Her work has been exhibited in group shows in Portland, Oregon; San Francisco; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Santa Fe, New Mexico. She was an artist in residence at Minot State University in her hometown of Minot, North Dakota. Check out Melissa Kaseman’s photographs.

Andrew Kuo is a New York–based artist, who has held solo shows at Marlborough Chelsea, Galleria Marabini, and Artists Space, among others. Check out the start of our series of infographics from Andrew Kuo.

Travis Larchuk is the head writer for NPR’s trivia, puzzle, and word play show Ask Me Another. Watch our interview with Travis Larchuk.

Javier Laspiur is a photographer based in Madrid, Spain. He is a senior art director at Comunica +A. Check out Javier Laspiur’s photographic series Consolas.

Mike Lazer-Walker makes interactive art, experimental games, and software tools. His work has been featured at IndieCade, the Game Developer’s Conference, the Smithsonian Museum and on NPR’s All Things Considered. Most of his work focuses on reframing everyday objects and spaces as playful experiences with nontraditional interaction models. Until recently, he worked with the MIT Media Lab’s Playful Systems research group. Read more from Mike Lazer-Walker.

J. Robert Lennon is the author of two story collections, Pieces For The Left Hand and See You in Paradise, and eight novels, including Mailman, Familiar, and Broken River. He teaches writing at Cornell University. Click through for J. Robert Lennon’s story game.

Colleen Macklin is a game designer, and associate professor of media design and co-director of Prototyping, Evaluation, Teaching and Learning Lab (PETLab), a public interest game design and research lab for interactive media, at Parsons School of Design. Her work has been shown at the Come Out and Play Festival, SoundLab, the Whitney Museum for American Art, and Creative Time. Watch our interview with Colleen Macklin.

Anne Miltenburg is a designer based in Nairobi, Kenya. An inveterate traveler, she has lived and worked across Europe, and in Mali, South Korea, Australia, and the U.S. Miltenburg is the founder of The Brandling. Read more from Anne Miltenburg.

Albert Mobilio is the author of several poetry collections and a fiction collection, Games and Stunts. Mobilio is an assistant professor of literary studies at the New School, an editor at Hyperallergic Weekend, and contributing editor at Bookforum. Check out the first story in our series from Albert Mobilio.

Anis Mojgani is a two-time National Poetry Slam Champion and winner of the International World Cup Poetry Slam. He is the author of five books. His latest is In the Pockets of Small Gods.

Susana Morris is a blogger, activist, and associate professor in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Institute of Technology. As co-founder of the Crunk Feminist Collective, she is committed to illuminating women’s stories and experiences. She is the author of Close Kin and Distant Relatives: The Paradox of Respectability in Black Women’s Literature. Read more from Susana Morris. Join us for the upcoming panel, Game Changers: Women Activists in Digital Space, with Angela Washko, Susana Morris, and Jane Friedhoff at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Sianne Ngai is professor of English at the University of Chicago specializing in American literature, literary and cultural theory, and feminist studies. She is the author of Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting and Ugly Feelings. Check out more from Sianne Ngai.

Jason Novak is a cartoonist. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Rumpus, and Harper’s Weekly, and more. Check out Adam Bessie and Jason Novak’s monthly comic, Board Gaming the System.

Sergio Pellis is a professor of animal behavior and neuroscience at the University of Lethbridge in Canada. A central focus of his research is on the evolution, development and neurobiology of play behavior. Read more from Sergio Pellis.

Alexander Perrin is an illustrator, technical artist, and game developer based in Melbourne, Australia. Perrin aims to create engaging, intuitive, and welcoming experiences that appeal to a wide range of players, including those who do not typically identify with the video game world. He is currently working alongside artist Josh Tatangelo at 2pt Design Studios to create considerate games and interactive media. Check out Alexander Perrin’s game A Short Trip.

Walker Pickering is a photographer and transmedia artist. A native Texan, he teaches photography, video, and bookmaking at the University of Nebraska. His work has been exhibited throughout the United States and internationally, and is included in a number of private and public collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and The Wittliff Collection of Southwestern & Mexican Photography. Take a look at Walker Pickering’s photographic series Esprit de Corps.

Artist Pedro Reyes lives and works in Mexico City. He has won international attention for large-scale projects that address current social and political issues. His varied practice utilizes sculpture, performance, video, and activism. Watch our interview with Pedro Reyes.

Randall Roberts is a Los Angeles-based writer and journalist who covers music culture for the The Los Angeles Times. His work can be found online at ballparkvillage.com. Read more from Randall Roberts.

Carlo Rotella is a professor of English at Boston College. His book Cut Time: An Education at the Fights was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Rotella’s work has also appeared in numerous publications, including the New York Times Magazine, Boston Globe, The New Yorker, Chicago Tribune, Harper’s Magazine, and The Believer. Check out Carlo Rotella’s work.

Molly Roth is a Michigan-born, Brooklyn-based graphic artist and humorist. She works on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker Daily Shouts, McSweeney’s, and Vox. Check out Josh Gondelman and Molly Roth’s comic series Games Adults Play.

Karen Russell is a renowned fiction writer and the author of Swamplandia!, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, Vampires in the Lemon Grove: Stories, and Sleep Donation: A Novella. Read Karen Russell’s thoughts on writing and play.

Naomi Russo is an Australian writer who generally covers design, art, and the environment. Her work has been published in the Atlantic and Australian Geographic. Read more from Naomi Russo.

Tamara Shopsin is a graphic designer and illustrator whose work is regularly featured in The New York Times and The New Yorker. She is the author of two memoirs, Mumbai New York Scranton and Arbitrary Stupid Goal. She is also designer of the 5 Year Diary, co-author with Jason Fulford of the photobook for children, This Equals That, and a cook at her family’s restaurant in New York City. Check out Tamara Shopsin’s piece.

Gwen Smith is a photographer living and working in New York. She describes herself as “an artist, a mother, a seeker, a finder, and a player.” Watch our interview with Gwen Smith.

Trevor Smith is Curator of the Present Tense at the Peabody Essex Museum and curator of PlayTime. He leads PEM’s Present Tense initiative, which celebrates the central role that creative expression plays in shaping our world today. Why PlayTime? Trevor Smith tells us more about the film that inspired the exhibition and its title.

Lizzie Stark is the author of Pandora’s DNA, which explores the history and science of the so-called ‘breast cancer genes,’ and Leaving Mundania, which investigates the subculture of live action roleplay, or LARP. Her journalism and essays have appeared in the Washington Post, Daily Beast, io9, Fusion, and Philadelphia Inquirer. Check out Lizzie Stark’s piece.

David Steinberg is a crossword puzzle constructor and editor. At fourteen, he became one of the youngest persons to ever publish a crossword puzzle with The New York Times, and has since authored two books of puzzles, Chromatics and Juicy Crosswords. Steinberg also founded the Pre-Shortzian Puzzle Project, a collaborative effort to build a digitized, fully analyzable database of New York Times crossword puzzles. David Steinberg’s custom PlayTime crossword can be found here.

Stanley Thangaraj is a socio-cultural anthropologist with interests in race, gender, sexuality, class, and ethnicity in Asian America in particular and in immigrant America in general. He is an assistant professor in the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership at the City College of New York. He is a former high school and collegiate athlete and coach who considers sport a key site to understand immigrant enculturation, racialization, and cultural citizenship. Read more from Stanley Thangaraj.

Photographer B.A. Van Sise’s work has been featured on the cover of The New York Times, in the pages of Newsday and the Washington Post, and on PBS NewsHour and NPR. A number of his portraits of notable American poets are in the collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Check out B.A. Van Sise’s photographs for PlayTime.

Tom Vanderbilt is a contributing editor of Wired (UK), Outside, and Artforum. He is the author of Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What It Says About Us), You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice, and Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America. Check out Tom Vanderbilt on foosball.

Rob Walker is a columnist for The New York Times Sunday Business section, and he contributes to many other publications, writing about design, technology, business, and the arts. His most recent book, co-edited with Joshua Glenn, is Significant Objects: 100 Extraordinary Stories About Ordinary Things. Walker and Glenn also oversee PROJECT:OBJECT, an ongoing series of personal stories about material possessions. Read more from Rob Walker.

Angela Washko is an artist, writer, and facilitator devoted to creating new forums for discussions of feminism in the spaces most hostile toward it. She is a visiting assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University. Since 2012, Washko has also been facilitating The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft. Watch our interview with Angela Washko. Join us for the upcoming panel, Game Changers: Women Activists in Digital Space, with Angela Washko, Susana Morris, and Jane Friedhoff at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm.

Boris Willis is Chief Artistic Officer of Boris Willis Moves and Associate Professor of Computer Game Design at George Mason University. Watch our interview with Boris Willis.

Christine Wong Yap is a New York–based artist. Her work has been exhibited in the San Francisco Bay area, as well as in New York, Los Angeles, Manila, Manchester, and more. Her work has been supported by the Queens Council on the Arts, the Jerome Foundation, and the Center for Cultural Innovation. Play Inter/de-pend-ence here.

Eric Zimmerman is a game designer and co-founder of the game studio Gamelab, game design collective Local No. 12, and The Institute of Play. He is a founding faculty and arts professor at the New York University Game Center in the Tisch School of the Arts. His book, Rules of Play (with Katie Salen), was published in 2003. Watch our interview with Eric Zimmerman.