Aesthetics as a philosophical discipline was an invention of the Enlightenment, and appropriately enough, most of the historical discussion has focused on the beautiful and the sublime. However, as J. L. Austin noted in “A Plea for Excuses,” the classic problems are not always the best site for fieldwork in aesthetics: “If only we could forget for a while about the beautiful and get down instead to the dainty and the dumpy.” Cultural theorist and literary critic Sianne Ngai has dedicated years of research to such marginal categories within aesthetics. She talks with Adam Jasper of Cabinet about her ideas.

Adam Jasper: You’ve written on cuteness, on envy, on boredom, and now on the interesting. If it could be said that there is a unified project behind these topics, what is it?

Sianne Ngai: I’m interested in states of weakness: in “minor” or non-cathartic feelings that index situations of suspended agency; in trivial aesthetic categories grounded in ambivalent or even explicitly contradictory feelings. More specifically, I’m interested in the surprising power these weak affects and aesthetic categories seem to have, in why they’ve become so paradoxically central to late capitalist culture. The book I’m currently completing is on the contemporary significance of three aesthetic categories in particular: the cute, the interesting, and the zany.

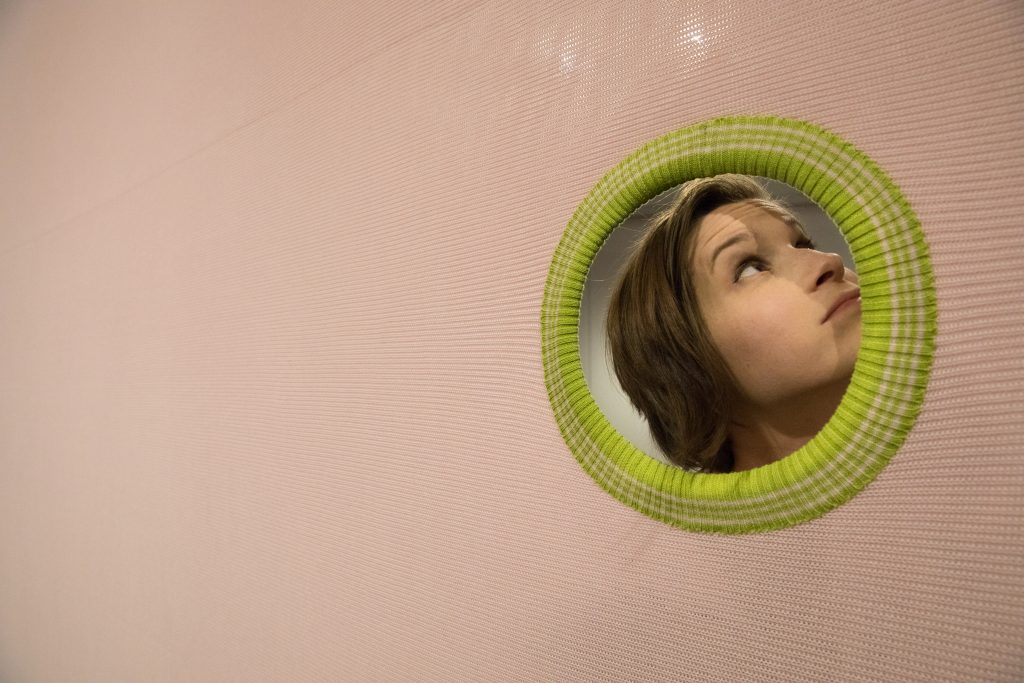

I focus on aesthetic experiences grounded in equivocal affects. In fact, the aesthetic categories that interest me most are ones grounded on feelings that explicitly clash. To call something cute, in vivid contrast to, say, beautiful, or disgusting, is to leave it ambiguous whether one even regards it positively or negatively. Yet who would deny that cuteness is an aesthetic, if not the dominant aesthetic of consumer society?

AJ: Can you say more about the qualities of non-cathartic feelings? The explicit rejection of catharsis was central to Brechtian theater, but is that what you are referring to here?

SN: By non-cathartic I just mean feelings that do not facilitate action, that do not lead to or culminate in some kind of purgation or release—irritation, for example, as opposed to anger. These feelings are therefore politically ambiguous, but good for diagnosing states of suspended agency, due in part to their diffusiveness and/or lack of definite objects.

AJ: To get our hands a little dirtier here, could you provide some examples of typically cute and typically zany things and indicate the characteristics that make them that way?

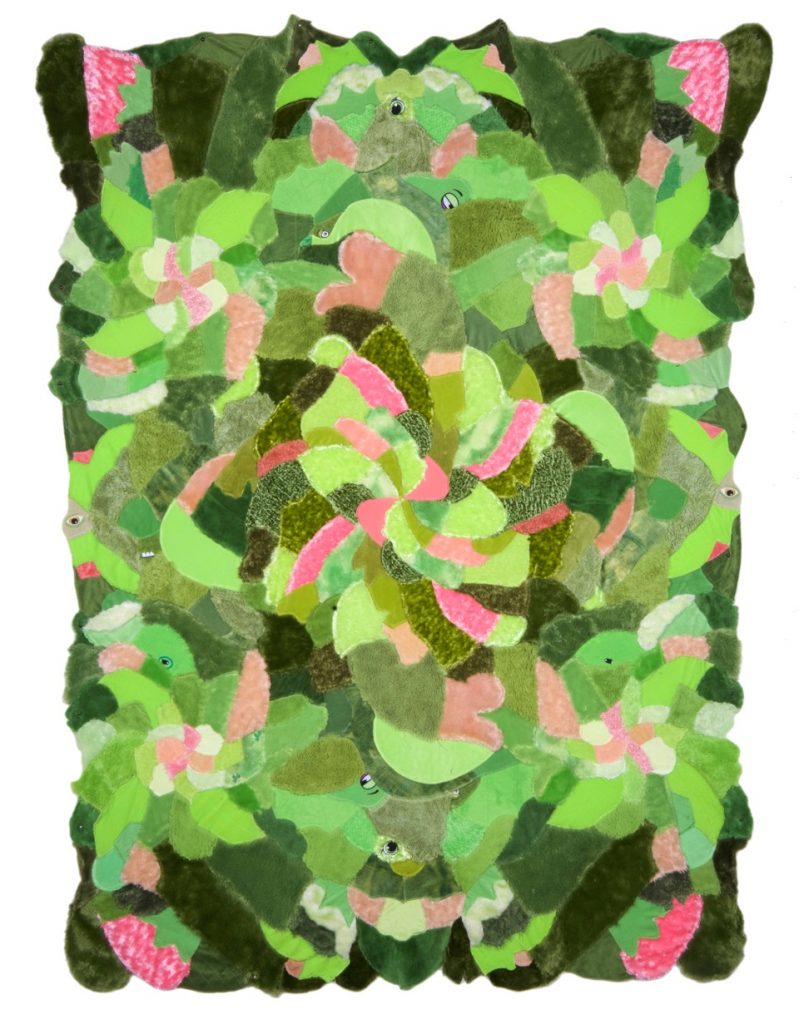

SN: Cuteness is a way of aestheticizing powerlessness. It hinges on a sentimental attitude toward the diminutive and/or weak, which is why cute objects—formally simple or noncomplex, and deeply associated with the infantile, the feminine, and the unthreatening—get even cuter when perceived as injured or disabled. So there’s a sadistic side to this tender emotion, as people like Daniel Harris have noted. The prototypically cute object is the child’s toy or stuffed animal.

Cuteness is also a commodity aesthetic, with close ties to the pleasures of domesticity and easy consumption. As Walter Benjamin put it: “If the soul of the commodity which Marx occasionally mentions in jest existed, it would be the most empathetic ever encountered in the realm of souls, for it would have to see in everyone the buyer in whose hand and house it wants to nestle.” Cuteness could also be thought of as a kind of pastoral or romance, in that it indexes the paradoxical complexity of our desire for a simpler relation to our commodities, one that tries in a utopian fashion to recover their qualitative dimension as use.

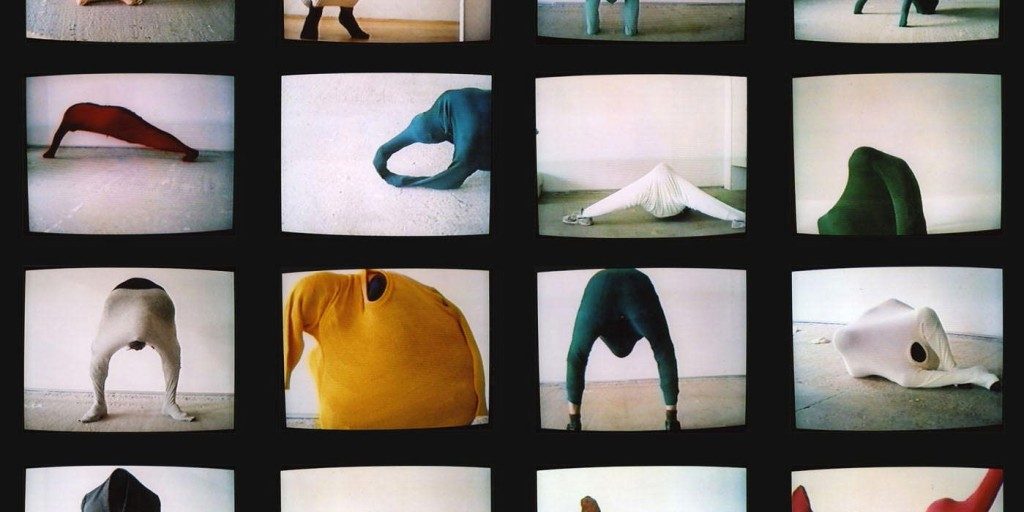

While the cute is thus about commodities and consumption, the zany is about performing. Intensely affective and highly physical, it’s an aesthetic of nonstop action that bridges popular and avant-garde practice across a wide range of media: from the Dada cabaret of Hugo Ball to the sitcom of Lucille Ball. You could say that zaniness is essentially the experience of an agent confronted by—even endangered by—too many things coming at her quickly and at once. Think here of Frogger, Kaboom!, or Pressure Cooker, early Atari 2600 video games in which avatars have to dodge oncoming cars, catch falling bombs, and meet incoming hamburger orders at increasing speeds. Or virtually any Thomas Pynchon novel, bombarding protagonist and reader with hundreds of informational bits which may or may not add up to a conspiracy.

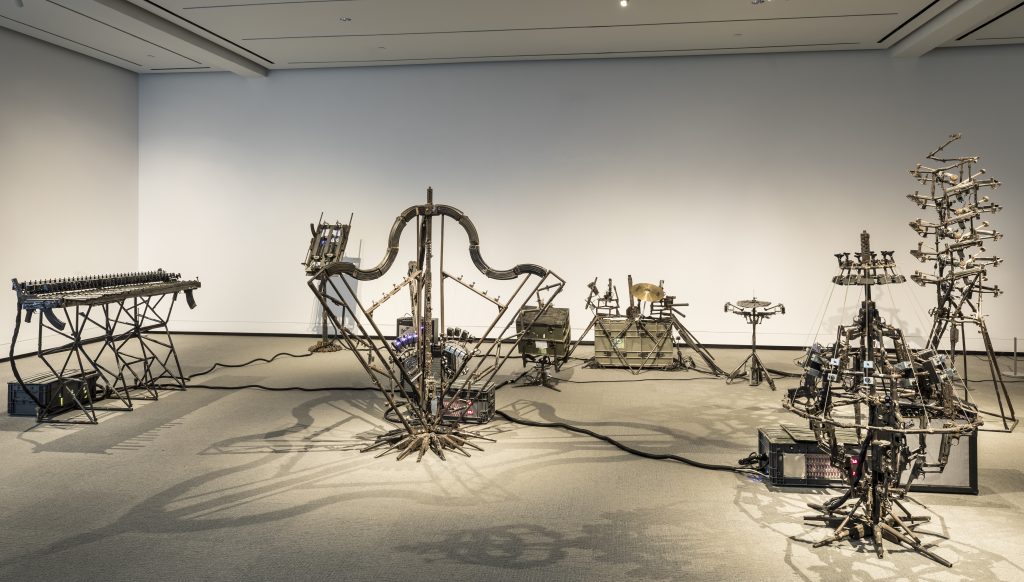

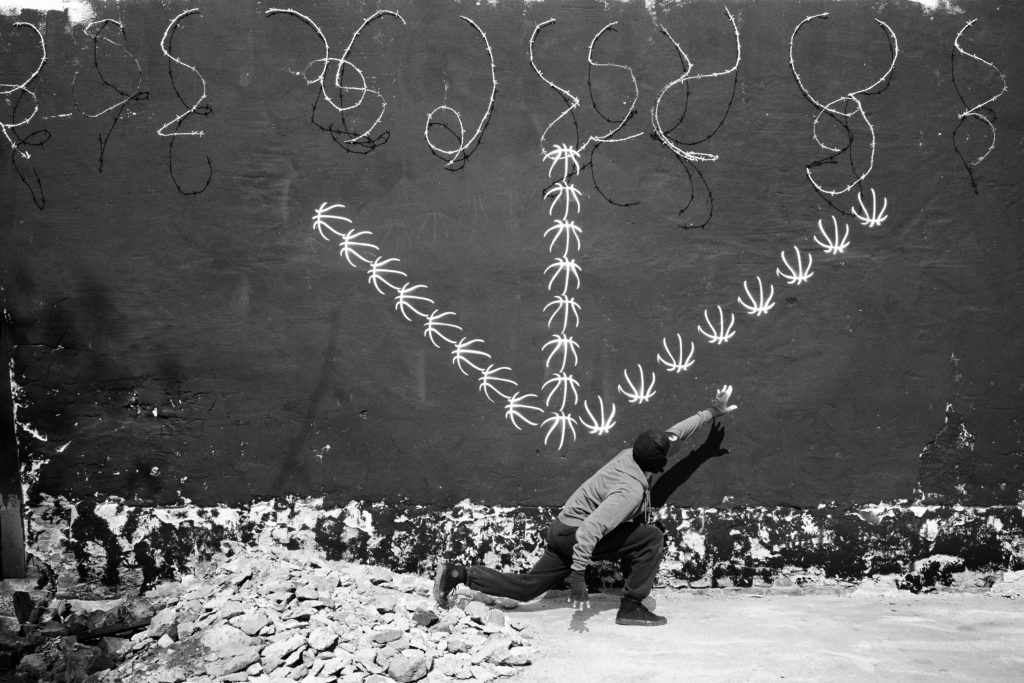

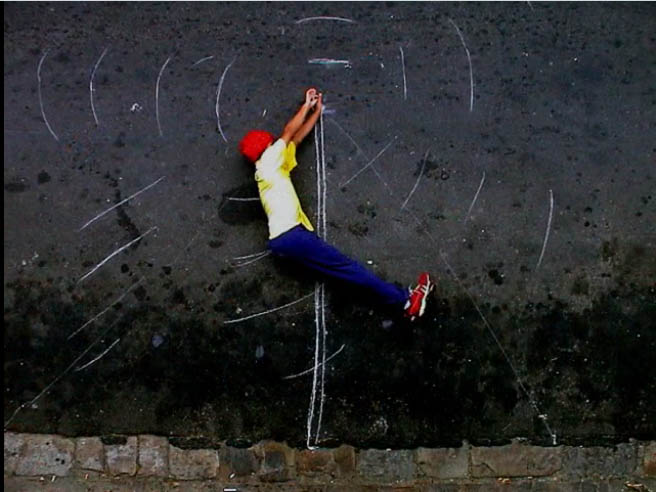

The dynamics of this aesthetic of incessant doing are thus perhaps best studied in the arts of live and recorded performance—dance, happenings, walkabouts, reenactments, game shows, video games. Yet zaniness is by no means exclusive to the performing arts. So much of “serious” postwar American literature is zany, for instance, that one reviewer’s description of Donald Barthelme’s Snow White—“a staccato burst of verbal star shells, pinwheel phrases, [and] cherry bombs of . . . . puns and wordplays”—seems applicable to the bulk of the post-1945 canon, from [John] Ashbery to Flarf; Ishmael Reed to Shelley Jackson.

I’ve got a more specific reading of post-Fordist or contemporary zaniness, which is that it is an aesthetic explicitly about the politically ambiguous convergence of cultural and occupational performance, or playing and laboring, under what Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello call the new “connexionist” spirit of capitalism. As perhaps exemplified best by the maniacal frivolity of the characters played by Ball in I Love Lucy, Richard Pryor in The Toy, and Jim Carrey in The Cable Guy, the zany more specifically evokes the performance of affective labor—the production of affects and relationships—as it comes to increasingly trouble the very distinction between work and play. This explains why this ludic aesthetic has a noticeably unfun or stressed-out layer to it. Contemporary zaniness is not just an aesthetic about play but about work, and also about precarity, which is why the threat of injury is always hovering about it. ♦

(This interview between Adam Jasper and Sianne Ngai was originally published in Cabinet magazine, issue 43, 2011. Image courtesy Janeen via Flickr.)